Lessico

Plauto

Commediografo latino (Sarsina, allora in Umbria, oggi in provincia di Forlì, ca. 254 - forse Roma 184 aC). Attore e impresario teatrale, perse ogni cosa in un dissesto finanziario e fu costretto per pagare i debiti a girare la macina di un mugnaio. In quel periodo avrebbe scritto tre commedie, il cui successo gli avrebbe assicurato il riscatto da quella condizione servile e l'inizio di una brillante carriera teatrale. La ricostruzione della sua biografia non va oltre questi dati o pochi altri ancora più incerti; anche il nome è dubbio: Marco Accio Plauto o Tito Maccio Plauto, dove il cognome Plauto verrebbe dal difetto fisico dei piedi piatti.

Dopo la

morte di Plauto circolarono sotto il suo nome 130 commedie. I grammatici

latini si accanirono per distinguere in esse le autentiche e le spurie. La

scelta più accreditata fu quella di Varrone![]() ,

che ne indicò come sicuramente autentiche 21, dubbie 19, sicuramente spurie

90.

,

che ne indicò come sicuramente autentiche 21, dubbie 19, sicuramente spurie

90.

Le 21 varroniane

sono quelle giunte fino a noi, e cioè: Amphitruo (Anfitrione), Asinaria

(La commedia degli asini), Aulularia![]() (La commedia della pentola), Bacchides (Le Bacchidi), Captivi (I

prigionieri), Casina (La sorteggiata), Cistellaria (La commedia

della cassetta), Curculio (Il roditore), Epidicus (Epidico), Menaechmi

(I Menecmi), Mercator (Il mercante), Miles gloriosus (Il soldato

millantatore), Mostellaria (La commedia dello spettro), Persa

(Il persiano), Poenulus (Il giovane cartaginese), Pseudolus

(La commedia della pentola), Bacchides (Le Bacchidi), Captivi (I

prigionieri), Casina (La sorteggiata), Cistellaria (La commedia

della cassetta), Curculio (Il roditore), Epidicus (Epidico), Menaechmi

(I Menecmi), Mercator (Il mercante), Miles gloriosus (Il soldato

millantatore), Mostellaria (La commedia dello spettro), Persa

(Il persiano), Poenulus (Il giovane cartaginese), Pseudolus![]() (Pseudolo), Rudens (La gomena), Stichus (Stico), Trinummus

(Le tre monete), Truculentus (Lo zoticone), Vidularia (La

commedia del baule; giunta mutila).

(Pseudolo), Rudens (La gomena), Stichus (Stico), Trinummus

(Le tre monete), Truculentus (Lo zoticone), Vidularia (La

commedia del baule; giunta mutila).

Difficile la datazione di tutte queste opere o almeno la loro disposizione cronologica, che si è tentato tuttavia di stabilire in vario modo (allusioni interne ad avvenimenti contemporanei, disposizione metrica, tecnica teatrale). Si propende oggi, nel complesso, a collocare fra le più antiche Mercator, Asinaria, Miles gloriosus, Cistellaria, a considerare centrali lo Stichus, Amphitruo, Menaechmi, Curculio, Rudens, Aulularia, Persa, Poenulus, Mostellaria, Epidicus, e tra le ultime Pseudolus, Bacchides, Trinummus, Captivi, Truculentus, Casina.

Sono tutte

commedie del genere delle palliate, ossia ambientate in Grecia e secondo lo

schema corrente della commedia greca nuova; ispirazione più frequente Plauto

trae da Difilo, Filemone e Menandro![]() .

Sui loro modelli inscrive poi degli spunti farseschi tradizionali, di

repertorio, derivati dall'antico teatro latino, osco, etrusco e arricchito da

spunti popolareschi; solo in qualche caso si può parlare di una vera e

propria contaminazione di più originali in un'unica opera (nel Miles

per esempio).

.

Sui loro modelli inscrive poi degli spunti farseschi tradizionali, di

repertorio, derivati dall'antico teatro latino, osco, etrusco e arricchito da

spunti popolareschi; solo in qualche caso si può parlare di una vera e

propria contaminazione di più originali in un'unica opera (nel Miles

per esempio).

Perciò le situazioni e la trama sono quasi costanti: giovani scapestrati a cui si oppongono genitori intransigenti, collaborazione di un servo astuto agli amori del giovane con una ragazza di umile condizione o con cortigiane sfruttate da lenoni; soluzione finale favorevole agli amanti, con premio per il servo. Poche le variazioni, come pure gli interventi collaterali di figure farsesche minori (cuochi, soldati, parassiti, cameriere, ecc.); anche i protagonisti sono irrigiditi in tipi, senza quasi mai alcuna nota psicologica che li caratterizzi singolarmente (qualche eccezione si può notare per esempio nel protagonista avaro dell'Aulularia o nel padre sofferente dei Captivi o nella giovane Selenio della Cistellaria).

La trama stessa contiene a volte delle incongruenze, delle complicazioni eccessive o degli sbandamenti, per la negligente inserzione in essa di spunti estranei. L'originalità di Plauto (difficile da stabilire anche per la perdita di tutti i suoi modelli greci) sta nella sapiente tecnica della composizione, nell'inventiva comica, soprattutto legata agli effetti delle parole e della metrica.

Plauto è totalmente volto al riso, al divertimento dello spettatore. Di qui le sue scoppiettanti invenzioni verbali, intrecci e giochi di parole, assonanze buffe, equivoci e oscenità, doppi sensi inesauribili. Uno stile che attinge largamente a modi e a effetti popolareschi, con colori di abbagliante immediatezza, ma anche rigoroso, ben studiato e portato con ogni mezzo a un chiaro livello letterario (Varrone ne fu entusiastico ammiratore).

In secondo

luogo Plauto si serve di una grande maestria metrica per introdurre sempre più

ampiamente nel dialogo squarci di ricca varietà ritmica, cantati con

accompagnamento musicale, che danno un crescente sapore di commedia musicale

ai suoi drammi. I cantica sono anzi l'aspetto più originale e tipico

del suo teatro. Forse già preesistenti nel teatro italico (accostati invece

da alcuni piuttosto alle parti liriche della tragedia greca), essi comunicano

alla commedia plautina varietà e sbrigliatezza fantastica, che si aggiunge,

con irresistibile effetto esilarante, alla rapidità del movimento scenico.

Tutto questo raggiunge spesso la sguaiatezza, e comunque Plauto non fa che

assecondare i gusti di un pubblico composito ma nel quale predomina l'elemento

popolare, e nello sfruttare, anche ripetutamente, mezzi scenici tradizionali

tanto che, più che al teatro ellenistico, il suo teatro può essere

avvicinato, per queste tecniche, per questi ritrovati e per questi effetti, a

quello di Aristofane![]() .

Il suo è del resto un “aceto” tipicamente italico, e tale rimane anche

nelle forme esteriori greche che assume.

.

Il suo è del resto un “aceto” tipicamente italico, e tale rimane anche

nelle forme esteriori greche che assume.

Tutto ciò

spiega il suo enorme successo popolare, accompagnato però anche,

miracolosamente, al compiacimento dei letterati. Plauto fu studiato da Elio

Stilone![]() ,

da Volcacio Sedigito, da Marco Varrone; eclissato dal classicismo in età

augustea, tornò a essere letto nel fervore arcaicizzante del sec. II dC.

,

da Volcacio Sedigito, da Marco Varrone; eclissato dal classicismo in età

augustea, tornò a essere letto nel fervore arcaicizzante del sec. II dC.

Più tardi godette il massimo favore del Rinascimento, con rappresentazioni e con imitazioni di L. B. Alberti, E. S. Piccolomini, dell'Ariosto, del Bibbiena, del Machiavelli, del Trissino; in Francia ispirò l'Avaro e l'Anfitrione di Molière, in Germania l'Amphitryon di Kleist, mentre in Inghilterra fu elaborato abbondantemente da Shakespeare nelle sue commedie.

Prende il titolo dalla pentola (lat. aulula, dim. di aula, olla) dove il vecchio avaro Euclione ha nascosto il suo tesoro, per sottrarlo a ladri immaginari. Dalla sua grottesca ossessione Euclione si libera quando, grazie all'astuzia del servo Strobilo, il tesoro diventa la dote della figlia del vecchio, Fedra, che potrà sposare il suo seduttore, Liconide. La figura plautina dell'avaro beffato ebbe innumerevoli imitazioni e fu ripresa da Molière ne L'avare. Questa commedia di Plauto risale a circa il 191 aC.

Captivi – I prigionieri

Personaggi

Ergastilo, parassita: è il personaggio più divertente della commedia. Perennemente bramoso di cibo e affamato, questo parassita tenta sempre di sbafare cibo. Diviene il primo testimone e annuncia a Egione l'arrivo della nave che riconduce a casa Filopolemo, garantendosi così il vitto a vita da parte di Egione.

Egione, vecchio: è il protagonista della commedia. Suo figlio, Filopolemo, viene catturato durante la guerra fra Etoli ed Eleati; egli decide allora di comprare il maggior numero possibile di schiavi Eleati sperando di trovarne qualcuno da poter scambiare con Filopolemo. È un uomo ricco e anziano, viene raggirato dal piano ideato da Filocrate, ma nonostante ciò, quando Filocrate torna da lui con Filopolemo, dimostra la sua lealtà liberandolo insieme al suo schiavo Tindaro, che si rivela essere il suo figlio rapito vent’anni prima.

Filocrate, giovane prigioniero: è il giovane Eleate comprato da Egione per riscattare il figlio. È un personaggio molto scaltro e intelligente: infatti è colui che escogita il piano di scambiare il nome e il ruolo con il suo servo Tindaro. Nonostante questo imbroglio nei confronti del suo padrone Egione, Filocrate risulta essere un personaggio onesto e leale poiché, anche se potrebbe essere libero, tornare in patria e lasciare il suo schiavo nelle mani di Egione, si adopera per poter ritrovare Filopolemo e, una volta ritrovatolo, lo riporta da suo padre per poter riscattare Tindaro e non mancare alla parola data.

Tindaro, servo di Filocrate, prigioniero: è di nascita libera, è figlio dello stesso Egione al quale era stato sottratto da uno schiavo all’età di quattro anni. Manifesta affetto e devozione nei confronti di Filocrate, suo padrone. Si scambia il nome con Filocrate ed è fiero di averlo salvato dalla servitù, si consola al pensiero che, se dovrà morire, la sua sarà una morte gloriosa. Viene però riconosciuto da Aristofonte e, per salvarsi, lo accusa di essere pazzo originando il dialogo più comico di tutta la commedia.

Aristofonte, giovane prigioniero: è l’incauto prigioniero che nulla sa dell’inganno, che conosce la vera identità di Tindaro e che determina la scoperta del piano. Aristofonte, irritato di fronte ai numerosi tentativi di Tindaro di metterne in dubbio la sincerità e la sanità mentale, diventa un inesorabile accusatore. Egli svolge dunque un ruolo determinante nello scioglimento dell’equivoco, ma in modo del tutto inopportuno, danneggiando Tindaro, suo compagno di schiavitù, e indirettamente Filocrate. Con la descrizione che Aristofonte fa del vero Filocrate, Egione comprende di essere stato ingannato.

Filopolemo, figlio d’Egione: non compare mai come personaggio attivo all’interno della commedia anche se tutta la vicenda si deve a lui. Egli è infatti il figlio di Egione catturato in battaglia dagli Eleati.

Stalagmo, servo d’Egione: questo servo è forse l’unico, nelle commedie plautine, privo di qualsiasi tratto positivo. Stalagmo è lo schiavo fuggitivo che aveva sottratto Tindaro da piccolo a Egione e che lo aveva venduto. Egli stesso riconosce di essere bugiardo, maligno e traditore.

Servi sferzatori: gli schiavi sferzatori non hanno un ruolo importante nella commedia. Sono i servi di Egione, hanno più che altro un ruolo funzionale poiché introducono o portano fuori scena alcuni personaggi.

Trama

Durante la guerra fra Etoli ed Elei, il figlio di Egione, Filopolemo, viene catturato; per riscattarlo il padre compra il maggior numero possibile di schiavi sperando di trovare qualcuno da poter scambiare con il figlio. Facendo ciò acquista anche Filocrate, nobile eleate, e il suo schiavo Tindaro. I due si scambiano nomi, ruoli e vesti; in questo modo Filocrate viene liberato al posto del suo schiavo per poter contrattare la liberazione di Filopolemo a Elea; successivamente Egione scopre l’inganno, grazie allo schiavo Aristofonte, e condanna Tindaro ai lavori forzati; ma subito dopo Filocrate ritorna con Filopolemo, figlio di Egione, e lo schiavo Stalagmo, che a Elea aveva venduto anni prima uno dei due figli di Egione. Quindi si scopre che Tindaro altri non è che il figlio rapito a Egione vent’anni prima; l’epilogo vede Tindaro liberato e riconosciuto come figlio da Egione, Stalagmo incatenato, Filocrate liberato e Filopolemo che ritorna finalmente a casa.

Commento

Questa breve ma intricata commedia di Plauto è definita la “commedia del buon costume”, poiché <<non vi sono qui versi sconci da non poter dire; non c’è in questa commedia il lenone spergiuro, né la cortigiana malvagia, né il soldato sbruffone>>(vv.55-58), come accade nella maggior parte delle commedie. Qui infatti <<Non vi si trovano né palpeggiamenti, né intrighi amorosi, né sostituzione di bimbi, né truffe di denaro. Qui non c’è il giovane innamorato che riscatta una sgualdrina di nascosto dal padre>>(vv.1030-1033). E viene aggiunto inoltre che <<Di commedie del genere, dove i buoni diventano migliori, i poeti ne creano poche>>(v.1034).

Tutta la storia si basa sull’inganno ai danni di Egione, che si risolve, però, con l’esaltazione dei valori affettivi che legano due giovani eccezionalmente uniti, nonostante l’appartenenza a livelli sociali differenti, una volta trovatisi entrambi nella condizione di schiavi.

Ma il tema centrale è sicuramente l’affetto paterno: infatti Egione è disposto a sacrificare anche il patrimonio familiare pur di poter riavere il proprio figlio, unico bene rimastogli, sano e salvo dalla prigionia. Il dolore dovuto alla scoperta dell’inganno esalta ancora di più questa tematica, e la carica di frustrazione, quella di un padre che aveva già perso tempo prima un figlio, rapitogli da uno schiavo.

Questa commedia mi ha affascinato, poiché riesce, partendo da un inganno, a non far risultare nessuno colpevole, anzi tutti sembrano da lodare e da stimare per il loro comportamento: Egione che tratta come persone vere gli schiavi, che erano sempre usati da tutti come se fossero animali; Tindaro che si sacrifica per l’amico e padrone Filocrate; e lo stesso Filocrate, che potendo anche abbandonare Tindaro, mantiene la promessa fatta a Egione, libera suo figlio e torna per riscattare l’amico.

Fabio Abbà - www.ghiacciato.it

Lucius Aelius Stilo Praeconinus, erudito e grammatico latino (Lanuvio 150 aC - ca. 90 aC). Si occupò per primo e intensamente a Roma di critica letteraria, grammatica e antichità. Tra i suoi allievi si annoverano Varrone e Cicerone. Commentò il Carmen Saliare e le leggi delle Dodici Tavole, pubblicò edizioni di Ennio e di Lucilio e stabilì il canone delle commedie di Plauto.

Tito Maccio Plauto

Tito Maccio Plauto (in latino: Titus Maccius Plautus o Titus Maccus Plautus; Sarsina, allora in Umbria, circa 254 aC – forse Roma184 aC) è stato un commediografo latino. Di origini umbre, venne in gioventù a contatto con il genere dell'atellana (tipo di commedia farsesca che ha come origine la farsa osca che fiorì in Campania prima del sec. IV aC). Giunto a Roma, divenne autore e attore di commedie palliatae, e fu il primo tra gli autori drammatici latini a specializzarsi nel solo genere comico.

Sulla biografia di Plauto si hanno poche notizie, nella maggior parte dei casi poco attendibili. Secondo la testimonianza di Cicerone, considerata verosimile, Plauto avrebbe avuto modo, in vecchiaia, di compiacersi della composizione dello Pseudolus, rappresentato per la prima volta nel 191 aC, e del Truculentus: poiché l'inizio della vecchiaia era fissato in Roma attorno ai sessant'anni, Plauto nacque tra il 255 e il 251 aC, probabilmente nel 254 aC Sua terra natale sarebbe stata la città di Sarsina, oggi in Romagna (provincia di Forlì) ma in epoca romana facente parte dell'Umbria; tale notizia, riportata dal cronista tardo Girolamo, sembra confermata da un passo della Mostellaria, ed è comunemente ritenuta vera.

Le notizie sulla maturità di Plauto furono anticamente tramandate dall'erudito di età tardo-repubblicana Marco Terenzio Varrone in alcune opere, oggi perdute, in cui trattava del teatro romano arcaico e in particolare di quello plautino. Egli stilò un'ordinata biografia dell'autore in cui raccolse il vasto corpus di notizie, in gran parte leggendarie, cui la fama che Plauto aveva ottenuto mentre era ancora in vita aveva dato adito. Nella stesura della sua opera, Varrone si accertò probabilmente di comprovare i riferimenti cronologici di cui si disponeva, e sottolineò inoltre la fioritura contemporanea di Plauto con Marco Porcio Catone detto il Censore. Le notizie riferite da Varrone, spesso estrapolate da alcuni passi delle commedie plautine in cui si credeva di vedere riferimenti autobiografici, andarono a costituire il racconto tradizionale della vita di Plauto. Dalle opere di Varrone attinsero informazioni Aulo Gellio, che trasmise alcuni aneddoti sulla vita e l'opera di Plauto nelle sue Noctes Atticae, e Gaio Svetonio Tranquillo, che le rielaborò nella sezione De poetis del suo De viris illustribus, pervenuto a oggi in maniera frammentaria. All'opera di Svetonio poté però rifarsi, tra il IV e il V secolo dC Sofronio Eusebio Girolamo.

Secondo le ricostruzioni più recenti, realizzate a partire dalle informazioni reperibili nei testi plautini e presso le opere degli antichi, e dall'analisi del contesto storico e culturale, Plauto avrebbe assistito in giovane età alle rappresentazioni teatrali dei testi tragici e comici greci organizzate in Roma e nelle città vicine, come Capua e Napoli, da attori di madrepatria greca o greco-italica. Contemporaneamente, avrebbe raggiunto un certo successo come attore di atellane, recitando nella parte di Maccus.

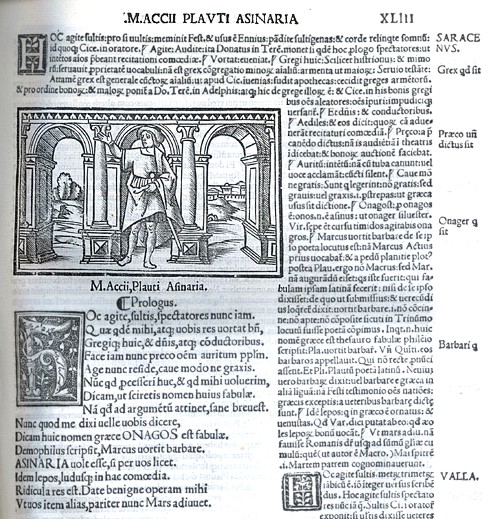

Il suo nome non è certo, infatti in alcune sue commedie si firma come Plautus in altre Maccius (nel prologo dell'Asinaria Maccus, nel prologo del Mercator Titus Maccius, nel prologo del Trinummus Plautus). Probabilmente sono tutti e due soprannomi usati dall'autore in momenti diversi della sua carriera, il primo deriva, secondo il lessicografo latino Festo (274, 9 Lindsay), da plotus, che in dialetto umbro significava "dalle grandi orecchie, dai piedi piatti" (cioè "attore di commedia"), mentre il secondo è desunto da un personaggio dell'Atellana, Maccus appunto, il che fa ritenere che Plauto fosse stato anche attore di atellane e che quest'ultime abbiano notevolmente influenzato la sua attività teatrale. Maccus è anche il nome di una maschera del teatro greco, alla quale si pensa Plauto si sia ispirato nel voler prendere in giro la nobiltà romana (infatti solo i nobili avevano i tre nomi), aggiungendo dunque al suo nomen e cognomen anche il terzo nome Maccus poi trasformato in Maccio.

Dopo la sua morte circolarono moltissime commedie intestate a lui (130) di cui buona parte si rivelarono in seguito dei falsi poiché molti commediografi minori, con l'intento di rendere le proprie commedie famose, le spacciavano per sue. Marco Terenzio Varrone 150 anni dopo la sua morte, le analizzò e le classificò in tre gruppi:

21 certamente plautine

19 di attribuzione incerta

90 spurie.

Dopo tale classificazione, le commedie incerte e quelle spurie non vennero più lette, e sono oggi andate perdute. Solo di due commedie sono certe le date di prima rappresentazione: lo Stichus (200 aC) e lo Pseudolus (191 aC).

Le commedie plautine per comodità didattica e anche per una certa affinità di struttura si possono catalogare in sei gruppi, come suggerito da Della Corte. Le commedie della beffa, del romanzesco, dell'agnizione, dei simillimi, della caricatura e di tipo composito. I titoli delle 21 commedie attribuite a Plauto sono i seguenti:

Amphitruo (Anfitrione): la storia narra le vicende di Anfitrione e del suo servo Sosia (da cui il termine omonimo, oggi usato per antonomasia come nome comune), i quali partono da Tebe in guerra. La storia narra del re di Tebe che va a combattere contro i Teleboi. Nel frattempo Giove, essendosi innamorato della moglie di Anfitrione, Alcmena, prende le sembianze del marito di lei per giacere con lei, e ordina al dio Mercurio di prendere le sembianze di Sosia. Tornato Anfitrione, egli manda il servo Sosia per annunciare del suo arrivo, ma egli incontra Mercurio trasformato che lo induce ad avere una crisi d'identità, convincendolo di non essere Sosia. Anfitrione, dopo aver ascoltato il discorso di Sosia tornato a riferire, torna dalla moglie e si crea confusione. La vicenda si conclude con l'agnizione (riconoscimento) finale e il tipico deus ex machina: Giove scende dal cielo e spiega la situazione. Annuncia inoltre alla coppia che avranno due figli gemelli, dei quali uno figlio di Giove, quindi semidio, il futuro Ercole.

Asinaria (La commedia degli asini): la trama della commedia racconta di Argirippo, un giovane, che vendendo degli asini, si guadagna i soldi per comprare la donna che ama, una cortigiana di nome Filenio. Quest'ultima però è anche desiderata dal padre di Argirippo, che incorre così nelle ire di sua moglie.

Aulularia (La commedia della pentola): un ricco e avaro signore, Euclione, ha nascosto in una pentola (in latino arcaico aula, per olla) il tesoro di casa, da lui improvvisamente ritrovato, e per avarizia vive comunque nella più squallida povertà. Euclione ha una figlia che vuole sposare con il ricco e anziano Megadoro. Tuttavia, un giovane, Liconide, ne è innamorato. Il servo del giovane trova la pentola e la dà al padrone permettendogli di sposare la figlia di Euclione.

Bacchides: due sorelle gemelle sono cortigiane e si chiamano entrambe Bacchide. Di esse si innamorano due giovani, Mnesiloco e il suo amico Pistoclero, i quali, per avere il denaro con cui riscattare una delle sorelle da un prestito che la tiene legata al soldato Cleomaco, si servono dell'aiuto dell'astuto servo di Mnesiloco, Crisalo, che raggira per ben due volte il padre del giovane per ottenere la somma. Alla fine i severi padri dei giovani, Nicobulo e Filosseno, accondiscendono agli amori dei loro figli e anzi paiono cedere essi stessi alle grazie delle due avvenenti cortigiane.

Captivi (I prigionieri; è l'unica commedia senza vicende amorose): durante la guerra tra Elide ed Etolia, un ricco proprietario terriero dell'Etolia, Egione, scopre che il figlio è stato fatto prigioniero. Compra così molti Elei per attuare uno scambio, tra i quali anche Filocrate, figlio di un latifondista Eleo, con il suo servo. Decide di mandare il servo per chiedere del figlio, ma i due avevano attuato uno scambio di persona. Tuttavia Filocrate torna con il figlio di Egione e nell'agnizione si scopre che il servo di Filocrate è figlio anch'egli di Egione.

Casina (La ragazza dal profumo di cannella): in essa ricorre il tema del contrasto tra un giovane e un vecchio (Lisidamo, padre del giovane, una figura di senex libertino) che s'innamorano della stessa ragazza, appunto Casina, una trovatella raccolta in casa da Lisidamo e da sua moglie Cleostrata. Naturalmente il conflitto si risolve al favore del giovane, a causa anche della ingegnosa opposizione di Cleostrata, che in questa commedia incarna la figura della uxor morosa ("moglie scorbutica, intrattabile").

Cistellaria (La commedia della cesta): Plauto in quest'opera scrive di una bambina trovata in una cesta e quando diventa grande s'innamora di un giovane promesso alla figlia di Demifone. Quando si scopre che la ragazza, Selenio, è figlia di Demifone avviene il matrimonio tra i due.

Curculio (Gorgoglione, propriamente verme roditore del grano): Curculio è un parassita che aiuta il suo protettore, il giovane Fedromo, a coronare il suo sogno d'amore. Riesce così a liberare una ragazza, Planesio, che il lenone Cappadoce aveva promesso a un soldato (che è poi riconosciuto come suo fratello); la ragazza alla fine si sposa con il giovane padrone di Curculio.

Epidicus (Epidico): Epidico è un servo che, con la sua scaltrezza, permette al suo padroncino Stratippocle di sposare una suonatrice di cetra. Non manca nella commedia il riconoscimento di una sorella di Stratippocle, una prigioniera conosciuta dal giovane in guerra.

Menaechmi (I Menecmi): racconta di due fratelli gemelli (Menecmo e Sosicle) che hanno vissuto in famiglie separate e che casualmente s'incontrano. È la tipica commedia degli equivoci dovuti a scambio di persona. Alla fine i due fratelli si riconoscono e tornano insieme nella terra natia.

Mercator (Il mercante): stesso tema di Casina con uguale epilogo. Un giovane (Carino) e il padre del giovane (Demifone) si invaghiscono della stessa ragazza. Alla fine le cose si mettono a posto e si suggerisce una scherzosa legge per i vecchi, imponendo a coloro che hanno compiuto 60 anni, siano sposati o scapoli, di non impelagarsi in avventure amorose.

Miles gloriosus (Il soldato spaccone): nella storia il soldato Pirgopolinice, tipico millantatore, viene beffato da un suo servo, l'ingegnoso Palestrione, che riesce a far ricongiungere il suo ex padroncino (Pleusicle) con la ragazza amata (Filocomasio). In Pirgopolinice sono riuniti, su un piano di comicità iperbolica e grottesca, i tratti del soldato smargiasso e del libertino impenitente (un "dongiovanni" ante litteram).

Mostellaria (La commedia del fantasma): in questa commedia un servo allontana il padrone anziano, improvvisamente tornato da un viaggio, dalla sua casa, per proteggere il padrone più giovane (e figlio del vecchio), con la scusa che è infestata da uno spirito.

Persa (Il persiano): originale fabula di Plauto che vede un astuto servo (Sagaristione), che, travestito da persiano, libera una ragazza (Lemniselenide) dal lenone Dordalo, per favorire i desideri di un amico, anch'egli servo (Tossilo). La caratteristica più importante di questa commedia è che i protagonisti sono eccezionalmente solo dei servi (oltre al lenone infine beffato).

Poenulus (Il cartaginese): Agorastocle, un giovane cartaginese rapito all'età di sette anni, vive in Etolia, adottato da un ricco signore. Accanto a lui abitano due sorelle, anch'esse rapite da piccole e ancora sfruttate dal loro padrone. Il giovane si innamora di una delle due sorelle, Adelfasio. Alla fine interviene il cartaginese Annone che riconosce in Agorastocle suo nipote e nelle sorelle le sue due figlie rapite. Agorastocle si sposa così con la cugina Adelfasio.

Pseudolus (Pseudolo): Pseudolo è il nome dello schiavo protagonista, assieme al lenone Ballione, della commedia. Quest'ultimo ha pattuito di cedere a un soldato macedone per venti mine la giovane Fenicia, di cui è innamorato Calidoro, padroncino di Pseudolo. Lo scaltrissimo servo riesce con i suoi raggiri a beffare il lenone e a consegnare la ragazza amata al suo padrone.

Rudens (La gomena): in questa palliata di ambientazione marinaresca due sorelle, cortigiane del lenone Labrace, naufragano durante una tempesta di mare e si rifugiano in un tempio, inseguite dal lenone. Un pescatore di nome Gripo, servo di Damone, che poi risulterà essere padre di una delle due ragazze, trascina con una gomena (rudens) un baule, preso nella rete in mare. Le ragazze scoprono, dai segni presenti nel baule, che sono libere, quindi non di proprietà del lenone.

Stichus (Stico): è una commedia che parla di fedeltà coniugale. Due spose, Panegiride e Panfila, che hanno i mariti (Epignomo e Panfilippo, tra di loro fratelli) in viaggio a caccia di ricchezze, resistono alle tentazioni del padre (Antifone) che vuole vederle risposate. Loro non cedono e alla fine della commedia tornano i mariti pieni di ricchezze. Stico è il nome del servo di uno dei due fratelli.

Trinummus (Le tre monete): la trama è impeniata sulla vicenda di un ragazzo scialacquatore (Lesbonico) che sperpera il patrimonio paterno e venderebbe anche la casa, se non intervenisse Callicle, un amico di famiglia, che è anche al corrente che il padre del giovane ha sotterrato in casa un tesoro segreto. Da questo tesoro egli ricava la dote con cui far sposare la sorella di Lesbonico. Per l'operazione di consegna della dote egli assolda un sicofante per "tre monete" (onde il titolo della commedia). Alla fine, con il ritorno del padre dall'estero, tutto si chiarisce.

Truculentus (Lo zoticone): la protagonista di questa commedia è una cortigiana di nome Fronesio, che inganna tre amanti e che è dipinta da Plauto come prostituta rapace e insaziabile, capace però di rendersi conto, in un bellissimo monologo, delle miserie della sua vita. Secondo Cicerone (De senectute 50) Plauto si compiaceva molto, da vecchio, di questa sua commedia, che ricava il titolo da un personaggio secondario, il servo rude e zotico di Strabace, uno degli innamorati della cortigiana.

Vidularia (La commedia del baule): i pochi frammenti della commedia (poco più di 100 versi) parlano di un baule (in latino vidulus) che contiene oggetti atti a far riconoscere (agnitio) il giovane Nicodemo. Non mancano punti di contatto con la trama della Rudens.

Tutte queste commedie sono state oggetto di studio e catalogate in sei gruppi:

dei simillini: riguarda lo scambio di persona, dello specchio e del doppio;

dell'agnizione: alla fine di questo tipo di commedie avviene un riconoscimento improvviso ed imprevedibile dell'identità di un personaggio;

della beffa: in questo tipo sono organizzati scherzi e beffe, bonari o meno;

del romanzesco: caratterizzate da intrecci complessi e avvincenti;

della caricatura: contenenti una rappresentazione iperbolica, esagerata di un personaggio;

composita: che racchiude al suo interno uno o più elementi delle sopraccitate tipologie.

Prima delle commedie vere e proprie, nella trascrizione manoscritta c'è quasi sempre un argumentum, cioè una sintesi della vicenda. In alcuni casi sono presenti addirittura due argumenta, e in questo caso uno dei due è acrostico ( le lettere iniziali dei singoli versi formano il titolo della commedia stessa). All'inizio delle commedie vi è un prologo, in cui un personaggio della vicenda, o una divinità, o un'entità astratta personificata presentano l'argomento che si sta per rappresentare. Nella commedia plautina possiamo distinguere, secondo una suddivisione già antica, i diverbia e i cantica , vale a dire le parti dialogate, con più attori che interloquiscono fra di loro, e le parti cantate, per lo più monologhi, ma a volte anche dialoghi tra due o addirittura tre personaggi. Nelle commedie di Plauto ricorre spesso lo schema dell'intrigo amoroso, con un giovane (adulescens) che si innamora di una ragazza. Il suo sogno d'amore incontra sempre dei problemi a tramutarsi in realtà a seconda della donna di cui si innamora: se è una cortigiana deve trovare i soldi per sposarla, se invece è onesta l'ostacolo è di tipo familiare. Ad aiutarlo a superare le varie difficoltà è il servus callidus (servo scaltro) o il parassita (squattrinato che lo aiuta in cambio di cibo) che con vari inganni e trabocchetti riesce a superare le varie difficoltà e a far sposare i due. Le beffe organizzate dal servo sono alcuni degli elementi più significativi della comicità plautina. Il servus è una delle figure più largamente utilizzate da Plauto nelle sue commedie, esso ha doti che lo fanno diventare eroe e beniamino dell'autore oltre che degli spettatori; esistono varie tipologie di servus:

il servus currens: l'attore che interpreta questo tipo di servo entra in scena di corsa e mantiene un atteggiamento trafelato finché rimane sul palcoscenico, Plauto lo utilizza come parodia del messaggero, infatti porta sempre qualche lettera o informazione che è di vitale importanza per l'avanzamento della commedia;

il servus callidus: è un tipo di servo la cui qualità più spiccata è appunto la calliditas (= astuzia), ordisce inganni benevoli/malevoli sia a favore che contro il protagonista (nello Pseudolus ad esempio il servo è centrale ed è colui che organizza la truffa);

il servus imperator: appare nella commedia Persa, è una tipologia di servo che sfoggia una parlantina che utilizza parole che derivano dal gergo militare e un'incredibile sfoggio di superbia. Parla di ciò che fa come se si rivolgesse a una truppa in partenza per una guerra.

Un altro elemento strutturale di grande importanza nelle commedie di Plauto è il riconoscimento finale (agnitio), grazie al quale vicende ingarbugliate trovano la loro fortunosa soluzione e ragazze che compaiono in scena come cortigiane o schiave recuperano la loro libertà e trovano l'amore.

La grande comicità generata dalle commedie di Plauto è prodotta da diversi fattori: un’oculata scelta del lessico, un sapiente utilizzo di espressioni e figure tratte dal quotidiano e una fantasiosa ricerca di situazioni che possano generare l’effetto comico. È grazie all’unione di queste trovate che si ha lo straordinario effetto dell’elemento comico che traspare da ogni gesto e da ogni parola dei personaggi. Questa uniforme presenza di comicità risulta più evidente in corrispondenza di situazioni ad alto contenuto comico. Infatti Plauto si serve di alcuni espedienti per ottenere maggior comicità, solitamente equivoci e scambi di persona.

Plauto fa uso anche di espressioni buffe e goliardiche che i vari personaggi molto di frequente pronunciano; oppure usa riferimenti a temi consueti, luoghi comuni, anche tratti dalla vita quotidiana, come il pettegolezzo delle donne. Inoltre Plauto fa largo uso dell'elemento corporeo (vedi corpo grottesco). Ad esempio questo dialogo della Aulularia in cui interagiscono i servi-cuochi Congrio e Antrace, e Strobilo che li coordina:

Secondo Atto, Scena 4. (Un'ora dopo)

Strobilo: (arrivando dal mercato

con due cuochi, due flautiste e varie provviste)

«Il padrone ha fatto la spesa in piazza, e ha ingaggiato i cuochi e queste

flautiste.

Mi ha anche ordinato di dividere tutte le sue cose, qui, in due parti.»

Antrace: «Per Giove, di me - te

lo dico chiaro e tondo - non farai due parti.

Se invece vuoi che me ne vada tutto intero da qualche parte, lo farò senza

meno.»

Congrio: (rivolto ad Antrace) «Quant'è

carina e riservata questa prostituta pubblica.

Se qualcuno volesse, non ti spiacerebbe, neh, di farti aprire in due dal di

dietro.» (vv. 280-6)

Le commedie di Plauto sono delle rielaborazioni in latino di commedie greche. Tuttavia, questi testi plautini non seguono molto l'originale perché Plauto da una parte adotta il procedimento della contaminatio, per il quale mescola insieme due o più canovacci greci, dall'altra aggiunge alle matrici elleniche cospicui tratti riconducibili a forme teatrali italiche come il mimo e l'atellana. Plauto tuttavia continua a mantenere nella sua commedia elementi ellenici quali i luoghi e i nomi dei personaggi (le commedie della recensione varroniana sono tutte palliatae, cioè di ambientazione greca). Possiamo affermare che Plauto prende molto dai modelli greci ma grazie ai cambiamenti e alle aggiunte il suo lavoro non risulta né una traduzione né un'imitazione pedissequa. A questo contribuisce anche l'adozione di una lingua latina vivacissima e pittoresca, in cui fanno spesso bella mostra di sé numerosissimi neologismi. La cosa che distingue l'imitatore dal grande scrittore è la capacità di quest'ultimo di farci dimenticare, tramite le sue aggiunte e le sue rielaborazioni, il testo di partenza. Sul tema della contaminatio c'è un'altra importante nota, il fatto che nei prologhi del Trinummus (verso 19) e dell'Asinaria (verso 11) Plauto definisce la propri traduzione con l'espressione latina "vortit barbare" (= tradotto in latino). Plauto utilizza il verbo latino vortere per indicare una trasformazione, un cambiamento di aspetto; si perviene necessariamente alla conclusione che Plauto non mirasse solamente a una traduzione linguistica ma anche letteraria. Il fatto poi che utilizzi l'avverbio barbare deriva dal fatto che essendo le sue fonti di ispirazione di origine greca, in latino erano rese con un notevole perdita di significato oltre che di artisticità, e dato che per i Greci tutto ciò che era straniero era chiamato barbarus, Plauto afferma che la propria traduzione è barbara.

Le opere di Plauto hanno ispirato molti drammaturghi come William Shakespeare, Molière, e Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Molte delle sue commedie sono state riproposte fino ai giorni nostri, talvolta rielaborate in chiave moderna. È il caso della commedia I Menecmi riadattata da Tato Russo a fine anni 80 in chiave partenopea; lo spettacolo ha avuto un grande successo, con più di 600 repliche nell'arco di 15 anni. Altre sue opere, il Miles gloriosus e lo Pseudolus sono alla base del musical A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (Una cosa buffa accaduta sulla strada che porta al Foro, in italiano "Dolci vizi al foro") del 1962, in seguito portata sullo schermo cinematografico da Richard Lester. Lo stesso tipo di personaggio (lo schiavo furbo) appare in Up Pompeii. Nel 1963 Pier Paolo Pasolini ha pubblicato presso l'editore Garzanti Il vantone, la sua traduzione in doppi settenari a rima baciata del Miles gloriosus; la lingua di Plauto è traslata in una lingua 'da avanspettacolo', con una leggera patina romanesca.

Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are among the earliest surviving intact works in Latin literature. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the genre devised by the innovator of Latin literature, Livius Andronicus. The word Plautine is used to refer to Plautus's works or works similar to or influenced by his.

Surviving plays

Amphitryon

Asinaria

Aulularia

Bacchides

Captivi

Casina

Cistellaria

Curculio

Epidicus

Menaechmi

Mercator

Miles Gloriosus

Mostellaria

Persa

Poenulus

Pseudolus

Rudens

Stichus

Trinummus

Truculentus

Vidularia (fragments)

The Haunted House

Little is known about Titus Maccius Plautus' early life. It is believed that he was born in Calabria, a region in "Magna Graecia" (called Greater Greece) in Southern Italy around 254 BCE. According to Morris Marples, Plautus worked as a stage-carpenter or scene-shifter in his early years. It is from this work, perhaps, that his love of the theatre originated. His acting talent was eventually discovered; and he adopted the names "Maccius" (a clownish stock-character in popular farces) and "Plautus" (a term meaning either "flat-footed" or "flat-eared," like the ears of a hound). Tradition holds that he made enough money to go into the nautical business, but that the venture collapsed. He is then said to have worked as a manual laborer and to have studied Greek drama — particularly the New Comedy of Menander — in his leisure. His studies allowed him to produce his plays, which were released between c. 205 and 184 BCE. Plautus attained such a popularity that his name alone became a hallmark of theatrical success. Plautus' comedies are mostly adapted from Greek models for a Roman audience, and are often based directly on the works of the Greek playwrights. He reworked the Greek texts to give them a flavour that would appeal to the local Roman audiences. They are among the earliest surviving intact works in Latin literature.

Plautus' epitaph read:

postquam

est mortem aptus Plautus, Comoedia luget,

scaena est deserta, dein Risus, Ludus Iocusque

et Numeri innumeri simul omnes conlacrimarunt.

Since

Plautus is dead, Comedy mourns,

Deserted is the stage; then Laughter, Jest and Wit,

And Melody's countless numbers all together wept.

Manuscript tradition

Plautus wrote around 52 plays, of which 20 have survived, making him the most prolific ancient dramatist in terms of surviving work. Despite this, the manuscript tradition of Plautus is poorer than that of any other ancient dramatist, something not helped by the failure of scholia on Plautus to survive. The chief manuscript of Plautus is a palimpsest, in which Plautus' plays had been scrubbed out to make way for Augustine's Commentary on the Psalms. The monk who performed this was more successful in some places than others. He seems to have begun furiously, scrubbing out Plautus' alphabetically-arranged plays with zest, before growing lazy, before finally regaining his vigour at the end of the manuscript to ensure not a word of Plautus was legible. Although modern technology has allowed classicists to view much of the effaced material, plays beginning in letters early in the alphabet have very poor texts (eg. the end of Aulularia and start of Bacchides are lost), plays with letters in the middle of the alphabet have decent texts, while only traces survive of the play Vidularia.

Historical context

The historical context within which Plautus wrote can be seen, to some extent, in his comments on contemporary events and persons. Plautus was a popular comedic playwright while Roman theatre was still in its infancy and still largely undeveloped. At the same time, the Roman Republic was expanding in power and influence.

Roman society deities

Plautus was sometimes accused of teaching the public indifference and mockery of the gods. Any character in his plays could be compared to a god. Whether to honour a character or to mock him, these references were demeaning to the gods. These references to the gods include a character comparing a mortal woman to a god, or saying he would rather be loved by a woman than by the gods. Pyrgopolynices from Miles Gloriosus (vs. 1265), in bragging about his long life, says he was born one day later than Jupiter. In Pseudolus, Jupiter is compared to Ballio the pimp. It is not uncommon, too, for a character to scorn the gods, as seen in Poenulus and Rudens. However, when a character scorns a god, it is usually a character of low standing, such as a pimp. Plautus perhaps does this to demoralize the characters. Soldiers often bring ridicule among the gods. Young men, meant to represent the upper social class, often belittle the gods in their remarks. Parasites, pimps, and courtesans often praise the gods with scant ceremony. Tolliver argues that drama both reflects and foreshadows social change. It is likely that there was already much scepticism about the gods in Plautus’ era. Plautus did not make up or encourage irreverence to the gods, but reflected ideas of his time. The state controlled stage productions, and Plautus’ plays would have been banned, had they been too risqué.

Gnaeus Naevius

Gnaeus Naevius, another Roman playwright of the late 3rd century BC, wrote tragedies and even founded the fabula praetexta (history plays), in which he dramatized historical events. He is known to have fought in the First Punic War and his birth, therefore, is placed around 280 BCE. His first tragedy took place in 235 BC. Plautus would have been living at the exact time as Naevius, but began writing later. Naevius is most famous for having been imprisoned by the Metelli and the Scipiones — two powerful families of the late 3rd century. Naevius’ imprisonment and eventual exile, an example of state censorship, may have influenced Plautus’ choice of subject matter and manner.

Second Punic War and Macedonian War

The Second Punic War occurred from 218–201 BC; its central event was Hannibal's invasion of Italy. M. Leigh has devoted an extensive chapter about Plautus and Hannibal in his recent book, Comedy and the Rise of Rome. He says that “the plays themselves contain occasional references to the fact that the state is at arms...” One good example is a piece of verse from the Miles Gloriosus, the composition date of which is not clear but which is often placed in the last decade of the 3rd century BCE. A. F. West believes that this is inserted commentary on the Second Punic War. In his article “On a Patriotic Passage in the Miles Gloriosus of Plautus”, he states that the war “engrossed the Romans more than all other public interests combined”. The passage seems intended to rile up the audience, beginning with hostis tibi adesse, or “the foe is near at hand”.

At the time, the general Scipio Africanus wanted to confront Hannibal, a plan

“strongly favoured by the plebs”. Plautus apparently pushes for the plan

to be approved by the senate, working his audience up with the thought of an

enemy in close proximity and a call to outmaneuver him. Therefore, it is

reasonable to say that Plautus, according to P.B. Harvey, was “willing to

insert [into his plays] highly specific allusions comprehensible to the

audience”. M. Leigh writes in his chapter on Plautus and Hannibal that

“the Plautus who emerges from this investigation is one whose comedies

persistently touch the rawest nerves in the audience for whom he writes”.

Later, coming of the heels of the conflict with Hannibal, Rome was preparing

to embark on another military mission, this time in Greece. While they would

eventually move on Philip V in the Second Macedonian War, there was

considerable debate beforehand about the course Rome should take in this

conflict. In the article “Bellum Philippicum: Some Roman and Greek Views

Concerning the Causes of the Second Macedonian War”, E. J. Bickerman writes

that “the causes of the fateful war … were vividly debated among both

Greeks and Romans”. Under the guise of protecting allies, Bickerman tells us,

Rome was actually looking to expand its power and control eastward now that

the Second Punic War was ended. But starting this war would not be an easy

task considering those recent struggles with Carthage — many Romans were too

tired of conflict to think of embarking on another campaign. As W. M. Owens

writes in his article “Plautus’ Stichus and the Political Crisis of 200

B.C.”, “There is evidence that antiwar feeling ran deep and persisted even

after the war was approved." Owens contends that Plautus was attempting

to match the complex mood of the Roman audience riding the victory of the

Second Punic War but facing the beginning of a new conflict. For instance, the

characters of the dutiful daughters and their father seem obsessed over the

idea of officium, the duty one has to do what is right. Their speech is

littered with words such as pietas and aequus, and they struggle to make their

father fulfil his proper role. The stock parasite in this play, Gelasimus, has

a patron-client relationship with this family and offers to do any job in

order to make ends meet; Owens puts forward that Plautus is portraying the

economic hardship many Roman citizens were experiencing due to the cost of

war. With the repetition of responsibility to the desperation of the lower

class, Plautus establishes himself firmly on the side of the average Roman

citizen. While he makes no specific reference to the possible war with Greece

or the previous war (that might be too dangerous), he does seem to push the

message that the government should take care of its own people before

attempting any other military actions.

Greek Old Comedy

In order to understand the Greek New Comedy of Menander and its similarities to Plautus, it is necessary to discuss, in juxtaposition with it, the idea of Greek Old Comedy and its evolution into New Comedy. The ancient Greek playwright that best embodies Old Comedy is Aristophanes. Aristophanes, a playwright of 5th century Athens, wrote plays of political satire such as The Wasps, The Birds and The Clouds. Each of these plays and the others that Aristophanes wrote are known for their critical political and societal commentary. This is the main component of Old Comedy. It is extremely conscious of the world in which it functions and analyzes that world accordingly. Comedy and theater were the political commentary of the time – the public conscience. In Aristophanes’ The Wasps, the playwright’s commentary is unexpectedly blunt and forward. For example, he names his two main characters “Philocleon” and “Bdelycleon”, which mean “pro-Cleon” and “anti-Cleon”, respectively. Simply the names of the characters in this particular play of Aristophanes make a political statement. Cleon was a major political figure of the time and through the actions of the characters about which he writes Aristophanes is able to freely criticize the actions of this prominent politician in public and through his comedy. Aristophanes underwent persecution for this.

Greek New Comedy

Greek New Comedy greatly differs from those plays of Aristophanes. The most notable difference, according to Dana F. Sutton is that New Comedy, in comparison to Old Comedy, is “devoid of a serious political, social or intellectual content” and “could be performed in any number of social and political settings without risk of giving offense”. The risk-taking for which Aristophanes is known is noticeably lacking in the New Comedy plays of Menander. Instead, there is much more of a focus on the home and the family unit — something that the Romans, including Plautus, could easily understand and adopt for themselves later in history.

Unlike Aristophanes, Plautus avoided current politics (in the narrow sense of the term) in his comedies. One main theme of Greek New Comedy is the father–son relationship. For example, in Menander’s Dis Exapaton there is a focus on the betrayal between age groups and friends. The father-son relationship is very strong and the son remains loyal to the father. The relationship is always a focus, even if it’s not the focus of every action taken by the main characters. In Plautus, on the other hand, the focus is still on the relationship between father and son, but we see betrayal between the two men that wasn’t seen in Menander. There is a focus on the proper conduct between a father and son that, apparently, was so important to Roman society at the time of Plautus.

This becomes the main difference and, also, similarity between Menander and Plautus. They both address “situations that tend to develop in the bosom of the family.” Both authors, through their plays, reflect a patriarchal society in which the father-son relationship is essential to proper function and development of the household. It is no longer a political statement, as in Old Comedy, but a statement about household relations and proper behaviour between a father and his son. But the attitudes on these relationships seem much different – a reflection of how the worlds of Menander and Plautus differed.

Farce

There are differences not just in how the father-son relationship is presented, but also in the way in which Menander and Plautus write their poetry. William S. Anderson discusses the believability of Menander versus the believability of Plautus and, in essence, says that Plautus’ plays are much less believable than those plays of Menander because they seem to be such a farce in comparison. He addresses them as a reflection of Menander with some of Plautus’ own contributions. Anderson claims that there is unevenness in the poetry of Plautus that results in “incredulity and refusal of sympathy of the audience.” This might be a reflection of an idea that the Romans were less sensitive to catering to the audience’s artistic sensibilities and more to their hunger for pure entertainment.

Prologues

The poetry of Menander and Plautus is best juxtaposed in their prologues. Robert B. Lloyd makes the point that “albeit the two prologues introduce plays whose plots are of essentially different types, they are almost identical in form…” He goes on to address the specific style of Plautus that differs so greatly from Menander. He says that the “verbosity of the Plautine prologues has often been commented upon and generally excused by the necessity of the Roman playwright to win his audience.” However, in both Menander and Plautus, word play is essential to their comedy. Plautus might seem more verbose, but where he lacks in physical comedy he makes up for it with words, alliteration and paronomasia (punning). Plautus is well known for his devotion to puns, especially when it comes to the names of his characters. In Miles Gloriosus, for instance, the female concubine’s name, Philocomasium, translates to “lover of a good party” — which is quite apt when we learn about the tricks and wild ways of this prostitute.

Character

Plautus’ characters — many of which seem to crop up in quite a few of his plays — also came from Greek stock, though they too received some Plautine innovations. Indeed, since Plautus was adapting these plays it would be difficult not to have the same kinds of characters—roles such as slaves, concubines, soldiers, and old men. By working with the characters that were already there but injecting his own creativity, as J.C.B. Lowe wrote in his article “Aspects of Plautus’ Originality in the Asinaria”, “Plautus could substantially modify the characterization, and thus the whole emphasis of a play.”

The clever slave

One of the best examples of this method is the Plautine slave, a form that plays a major role in quite a few of Plautus’ works. The “clever slave” in particular is a very strong character; he not only provides exposition and humor, but also often drives the plot in Plautus’ plays. C. Stace argues that Plautus took the stock slave character from New Comedy in Greece and altered it for his own purposes. In New Comedy, he writes, “the slave is often not much more than a comedic turn, with the added purpose, perhaps, of exposition”. This shows that there was precedent for this slave archetype, and obviously some of its old role continues in Plautus (the expository monologues, for instance). However, because Plautus found humor in slaves tricking their masters or comparing themselves to great heroes, he took the character a step further and created something distinct.

Understanding of Greek by Plautus’ audience

Of the approximate 270 proper names in the surviving plays of Plautus, about 250 names are Greek.] William M. Seaman proposes that these Greek names would have delivered a comic punch to the audience because of its basic understanding of the Greek language. This previous understanding of Greek language, Seaman suggests, comes from the “experience of Roman soldiers during the first and second Punic wars. Not only did men billeted in Greek areas have opportunity to learn sufficient Greek for the purpose of everyday conversation, but they were also able to see plays in the foreign tongue.” Having an audience with knowledge of the Greek language, whether limited or more expanded, allowed Plautus more freedom to use Greek references and words. Also, by using his many Greek references and showing that his plays were originally Greek, “It is possible that Plautus was in a way a teacher of Greek literature, myth, art and philosophy; so too was he teaching something of the nature of Greek words to people, who, like himself, had recently come into closer contact with that foreign tongue and all its riches.” At the time of Plautus, Rome was expanding, and having much success in Greece. W.S. Anderson has commented that Plautus “is using and abusing Greek comedy to imply the superiority of Rome, in all its crude vitality, over the Greek world, which was now the political dependent of Rome, whose effete comic plots helped explain why the Greeks proved inadequate in the real world of the third and second centuries, in which the Romans exercised mastery".

Plautus: copycat or creative playwright?

Plautus was known for the use of Greek style in his plays, as part of the tradition of the variation on a theme. This has been a point of contention among modern scholars. One argument states that Plautus writes with originality and creativity — the other, that Plautus is a copycat of Greek New Comedy and that he makes no original contribution to playwriting. A single reading of the Miles Gloriosus leaves the reader with the notion that the names, place, and play is Greek, but one must look beyond these superficial interpretations. W.S. Anderson would steer any reader away from the idea that Plautus’ plays are somehow not his own or at least only his interpretation. Anderson says that, “Plautus homogenizes all the plays as vehicles for his special exploitation. Against the spirit of the Greek original, he engineers events at the end... or alter[s] the situation to fit his expectations.” Anderson’s vehement reaction to the co-opting of Greek plays by Plautus seems to suggest that they are in no way like their originals were. It seems more likely that Plautus was just experimenting putting Roman ideas in Greek forms. Greece and Rome, although always put into the same category, were different societies with different paradigms and ways-of-life. W. Geoffrey Arnott says that “we see that a set of formulae [used in the plays] concerned with characterization, motif, and situation has been applied to two dramatic situations which possess in themselves just as many difference as they do similarities.” It is important to compare the two authors and the remarkable similarities between them because it is essential in understanding Plautus. He writes about Greeks like a Greek. However, Plautus and the writers of Greek New Comedy, such as Menander, were writing in two completely different contexts.

Contaminatio

One idea that is important to recognize is that of contaminatio, which refers to the mixing of elements of two or more source plays. Plautus, it seems, is quite open to this method of adaptation, and quite a few of his plots seem stitched together from different stories. One excellent example is his Bacchides and its supposed Greek predecessor, Menander’s Dis Exapaton. The original Greek title translates as “The Man Deceiving Twice”, yet the Plautine version has three tricks. V. Castellani commented that: Plautus’ attack on the genre whose material he pirated was, as already stated, fourfold. He deconstructed many of the Greek plays’ finely constructed plots; he reduced some, exaggerated others of the nicely drawn characters of Menander and of Menander’s contemporaries and followers into caricatures; he substituted for or superimposed upon the elegant humor of his models his own more vigorous, more simply ridiculous foolery in action, in statement, even in language.

By exploring ideas about Roman loyalty, Greek deceit, and differences in ethnicity, “Plautus in a sense surpassed his model.” He was not content to rest solely on a loyal adaptation that, while amusing, was not new or engaging for Rome. Plautus took what he found but again made sure to expand, subtract, and modify. He seems to have followed the same path that Horace did, though Horace is much later, in that he is putting Roman ideas in Greek forms. He not only imitated the Greeks, but in fact distorted, cut up, and transformed the plays into something entirely Roman. In essence it is Greek theater colonized by Rome and its playwrights.

Stagecraft

In Ancient Greece during the time of New Comedy, from which Plautus drew so much of his inspiration, there were permanent theaters that catered to the audience as well as the actor. The greatest playwrights of the day had quality facilities in which to present their work and, in a general sense, there was always enough public support to keep the theater running and successful. However, this was not the case in Rome during the time of the Republic, when Plautus wrote his plays. While there was public support for theater and people came to enjoy tragedy and comedy alike, there was also a notable lack of governmental support. No permanent theater existed in Rome until Pompey dedicated one in 55 BCE in the Campus Martius. The lack of a permanent space was a key factor in Roman theater and Plautine stagecraft. This lack of permanent theaters in Rome until 55 BCE has puzzled contemporary scholars of Roman drama. In their introduction to the Miles Gloriosus, Hammond, Mack and Moskalew say that “the Romans were acquainted with the Greek stone theater, but, because they believed drama to be a demoralizing influence, they had a strong aversion to the erection of permanent theaters.” This worry rings true when considering the subject matter of Plautus’ plays. The unreal becomes reality on stage in his work. T. J. Moore notes that, “all distinction between the play, production, and ‘real life’ has been obliterated [Plautus’ play Curculio]”. A place where social norms were upended was inherently suspect. The aristocracy was afraid of the power of the theater. It was merely by their good graces and unlimited resources that a temporary stage would have been built during specific festivals.

The importance of the Ludi

Roman drama, specifically Plautine comedy, was acted out on stage during the ludi or festival games. In his discussion of the importance of the ludi Megalenses in early Roman theatre, John Arthur Hanson says that this particular festival “provided more days for dramatic representations than any of the other regular festivals, and it is in connection with these ludi that the most definite and secure literary evidence for the site of scenic games has come down to us”. Because the ludi were religious in nature, it was appropriate for the Romans to set up this temporary stage close to the temple of the deity being celebrated. S.M. Goldberg notes that “ludi were generally held within the precinct of the particular god being honored.”

T. J. Moore notes that “seating in the temporary theaters where Plautus’ plays were first performed was often insufficient for all those who wished to see the play, that the primary criterion for determining who was to stand and who could sit was social status”. This is not to say that the lower classes did not see the plays; but they probably had to stand while watching. Plays were performed in public, for the public, with the most prominent members of the society in the forefront.

The wooden stages on which Plautus' plays appeared were shallow and long with three openings in respect to the scene-house. The stages were significantly smaller than any Greek structure familiar to modern scholars. Because theater was not a priority during Plautus' time, the structures were built and dismantled within a day. Even more practically, they were dismantled quickly due to their potential as fire-hazards.

Geography of the stage

Often the geography of the stage and more importantly the play matched the geography of the city so that the audience would be well oriented to the locale of the play. Moore says that, “references to Roman locales must have been stunning for they are not merely references to things Roman, but the most blatant possible reminders that the production occurs in the city of Rome.” So, Plautus seems to have choreographed his plays somewhat true-to-life. To do this, he needed his characters to exit and enter to or from whatever area their social standing would befit. Two scholars, V. J. Rosivach and N. E. Andrews, have made interesting observations about stagecraft in Plautus: V. J. Rosivach writes about identifying the side of the stage with both social status and geography. He says that, for example, “the house of the medicus lies offstage to the right. It would be in the forum or thereabouts that one would expect to find a medicus.” Moreover, he says that characters that oppose one another always have to exit in opposite directions. In a slightly different vein, N.E. Andrews discusses the spatial semantics of Plautus; he has observed that even the different spaces of the stage are thematically charged. He states: Plautus’ Casina employs these conventional tragic correlations between male/outside and female/inside, but then inverts them in order to establish an even more complex relationship among genre, gender and dramatic space. In the Casina, the struggle for control between men and women... is articulated by characters’ efforts to control stage movement into and out of the house.

Andrews makes note of the fact that power struggle in the Casina is evident in the verbal comings and goings. The words of action and the way that they are said are important to stagecraft. The words denoting direction or action such as abeo (“I go off”), transeo (“I go over”), fores crepuerunt (“the doors creak”), or intus (“inside”), which signal any character’s departure or entrance, are standard in the dialogue of Plautus’ plays. These verbs of motion or phrases can be taken as Plautine stage directions since no overt stage directions are apparent. Often, though, in these interchanges of characters, there occurs the need to move on to the next act. Plautus then might use what is known as a “cover monologue”. About this S.M. Goldberg notes that, “it marks the passage of time less by its length than by its direct and immediate address to the audience and by its switch from senarii in the dialogue to iambic septenarii. The resulting shift of mood distracts and distorts our sense of passing time.”

Relationship with the audience

The small stages had a significant effect on the stagecraft of ancient Roman theater. Because of this limited space, there was also limited movement. Greek theater allowed for grand gestures and extensive action to reach the audience members who were in the very back of the theater. However the Romans would have had to depend more on their voices than large physicality. There was not an orchestra available like there was for the Greeks and this is reflected in the notable lack of a chorus in Roman drama. The replacement character that acts as the chorus would in Greek drama is often called the “prologue.” Goldberg says that, “these changes fostered a different relationship between actors and the space in which they performed and also between them and their audiences.” Actors were thrust into much closer audience interaction. Because of this, a certain acting style became required that is more familiar to modern audiences. Because they would have been in such close proximity to the actors, ancient Roman audiences would have wanted attention and direct acknowledgement from the actors. Because there was no orchestra, there was no space separating the audience from the stage. The audience could stand directly in front of the elevated wooden platform. This gave them the opportunity to look at the actors from a much different perspective. They would have seen every detail of the actor and hear every word he said. The audience member would have wanted that actor to speak directly to them. It was a part of the thrill of the performance, as it is to this day.

Stock characters

Plautus’ range of characters was created through his use of various techniques, but probably the most important is his use of stock characters and situations in his various plays. He incorporates the same stock characters constantly, especially when the character type is amusing to the audience. As Walter Juniper wrote, “Everything, including artistic characterization and consistency of characterization, were sacrificed to humor, and character portrayal remained only where it was necessary for the success of the plot and humor to have a persona who stayed in character, and where the persona by his portrayal contributed to humor.” For example, in Miles Gloriosus, the titular “braggart soldier” Pyrgopolynices only shows his vain and immodest side in the first act, while the parasite Artotrogus exaggerates Pyrgopolynices’ achievements, creating more and more ludicrous claims that Pyrgopolynices agrees to without question. These two are perfect examples of the stock characters of the pompous soldier and the desperate parasite that appeared in Plautine comedies. In disposing of highly complex individuals, Plautus was supplying his audience with what it wanted, since “the audience to whose tastes Plautus catered was not interested in the character play,”[56] but instead wanted the broad and accessible humor offered by stock set-ups. The humor Plautus offered, such as “puns, word plays, distortions of meaning, or other forms of verbal humor he usually puts them in the mouths of characters belonging to the lower social ranks, to whose language and position these varieties of humorous technique are most suitable,” matched well with the stable of characters.

The Clever Slave

In his article "The Intriguing Slave in Greek Comedy," Philip Harsh gives evidence to show that the clever slave is not an invention of Plautus. While previous critics such as A. W. Gomme believed that the slave was “[a] truly comic character, the devisor of ingenious schemes, the controller of events, the commanding officer of his young master and friends, is a creation of Latin comedy,” and that Greek dramatists such as Menander did not use slaves in such a way that Plautus later did, Harsh refutes these beliefs by giving concrete examples of instances where a clever slave appeared in Greek comedy. For instance, in the works of Athenaeus, Alciphron, and Lucian there are deceptions that involve the aid of a slave, and in Menander’s Dis Exapaton there was an elaborate deception executed by a clever slave that Plautus mirrors in his Bacchides. Evidence of clever slaves also appears in Menander’s Thalis, Hypobolimaios, and from the papyrus fragment of his Perinthia. Harsh acknowledges that Gomme’s statement was probably made before the discovery of many of the papyri that we now have. While it was not necessarily a Roman invention, Plautus did develop his own style of depicting the clever slave. With larger, more active roles, more verbal exaggeration and exuberance, the slave was moved by Plautus further into the front of the action. Because of the inversion of order created by a devious or witty slave, this stock character was perfect for achieving a humorous response and the traits of the character worked well for driving the plot forward.

The Lusty Old Man

Another important Plautine stock character, discussed by K.C. Ryder, is the senex amator. A senex amator is classified as an old man who contracts a passion for a young girl and who, in varying degrees, attempts to satisfy this passion. In Plautus these men are Demaenetus (Asinaria), Philoxenus and Nicobulus (Bacchides), Demipho (Cistellaria), Lysidamus (Casina), Demipho (Mercator), and Antipho (Stichus). Periplectomenos (Miles Gloriosus) and Daemones (Rudens) are regarded as senes lepidi because they usually keep their feelings within a respectable limit. All of these characters have the same goal, to be with a younger woman, but all go about it in different ways, as Plautus could not be too redundant with his characters despite their already obvious similarities. What they have in common is the ridicule with which their attempts are viewed, the imagery that suggests that they are motivated largely by animal passion, the childish behavior, and the reversion to the love-language of their youth.

Female characters

In examining the female role designations of Plautus's plays, Z.M. Packman found that they are not as stable as their male counterparts: a senex will usually remain a senex for the duration of the play but designations like matrona, mulier, or uxor at times seem interchangeable. Most free adult women, married or widowed, appear in scene headings as mulier, simply translated as “woman”. But in Plautus’ Stichus the two young women are referred to as sorores, later mulieres, and then matronae, all of which have different meanings and connotations. Although there are these discrepancies, Packman tries to give a pattern to the female role designations of Plautus. Mulier is typically given to a woman of citizen class and of marriageable age or who has already been married. Unmarried citizen-class girls, regardless of sexual experience, were designated virgo. Ancilla was the term used for female household slaves, with Anus reserved for the elderly household slaves. A young woman who is unwed due to social status is usually referred to as meretrix or “courtesan.” A lena, or adoptive mother, may be a woman who owns these girls.

Unnamed characters

Like Packman, George Duckworth uses the scene headings in the manuscripts to support his theory about unnamed Plautine characters. There are approximately 220 characters in the 20 plays of Plautus. Thirty are unnamed in both the scene headings and the text and there are about nine characters who are named in the ancient text but not in any modern one. This means that about 18% of the total number of characters in Plautus are nameless. Most of the very important characters have names while most of the unnamed characters are of less importance. However, there are some abnormalities—the main character in Casina is not mentioned by name anywhere in the text. In other instances, Plautus will give a name to a character that only has a few words or lines. One explanation is that some of the names have been lost over the years; and for the most part, major characters do have names.

The language and style

The language and style of Plautus is not easy or simple. He wrote in a colloquial style far from the codified form of Latin that is found in Ovid or Virgil. This colloquial style is the everyday speech that Plautus would’ve been familiar with, yet that means that most students of Latin are unfamiliar with it. Adding to the unfamiliarity of Plautine language is the inconsistency of the irregularities that occur in the texts. In one of his prolific word-studies, A.W. Hodgman noted that: the statements that one meets with, that this or that form is "common," or "regular," in Plautus, are frequently misleading, or even incorrect, and are usually unsatisfying.... I have gained an increasing respect for the manuscript tradition, a growing belief that the irregularities are, after all, in a certain sense regular. The whole system of inflexion — and, I suspect, of syntax also and of versification—was less fixed and stable in Plautus’ time than it became later.

Plautine diction is distinctive in its use of archaic Latin forms. Some might find these difficult to understand. Plautus did not set out to write a play in archaic Latin; the term archaic merely comes from later perspective on the text. Most scholars note that the plays' language is written in a colloquial, everyday speech. M. Hammond, A.H. Mack, and W. Moskalew have noted in their introduction to the text of the Miles Gloriosus that Plautus was, “free from convention... [and that] he sought to reproduce the easy tone of daily speech rather than the formal regularity of oratory or poetry. Hence, many of the irregularities which have troubled scribes and scholars perhaps merely reflect the everyday usages of the careless and untrained tongues which Plautus heard about him.” Looking at the overall use of archaisms within Plautus, one will notice that they commonly occur in promises, agreements, threats, prologues, or speeches. Plautus uses archaic forms, though sometimes for metrical convenience, but more often for stylistic effect. There are many manifestations of these archaic forms in the texts of Plautus’ plays, in fact too many to completely include them in this article. Here the most regular of irregularities, i.e., archaisms, will be delineated:

the use of uncontracted forms of some verbs like malo

the emendation of the final -e of singular imperatives

the use of -o in some verb stems where it would normally be -e

the use of the -ier ending for the present passive and deponent infinitive

often the forms of sum are joined to the preceding word

the deletion of the final -s and final -e when ne is added to a second

singular verb

the replacement of -u with -o in noun endings

the use of qu instead of c, as in quom instead of cum

the use of the -ai genitive singular ending

the addition of a final -d onto personal pronouns in the accusative or

ablative

there is sometimes the addition of a final -pte, -te, or -met to pronouns

the use of -is as the nominative plural ending.

These peculiarities are the most common in the plays of Plautus, and their notation should make initial readings a bit easier. Archaic word forms in Plautus reflect the way that his contemporaries interacted. Plautus’ use of colloquial dialogue aids in understanding, to a certain extent, how the Romans greeted each other. For example, there are certain formulaic greetings such as “hello” and “how are you?” that elicit a certain formulaic response such as a returning hello, or an indication of one's state of being. Quid agis here would mean, “How are you?” These archaic forms present the reader with a richer understanding of the Latin language.

Means of expression

There are certain ways in which Plautus expressed himself in his plays, and these individual means of expression give a certain flair to his style of writing. The means of expression are not always specific to the writer, i.e., idiosyncratic, yet they are characteristic of the writer. Two examples of these characteristic means of expression are the use of proverbs and the use of Greek language in the plays of Plautus. Plautus employed the use of proverbs in many of his plays. Proverbs would address a certain genre such as law, religion, medicine, trades, crafts, and seafaring. Plautus’ proverbs and proverbial expressions number into the hundreds. They sometimes appear alone or interwoven within a speech. The most common appearance of proverbs in Plautus appears to be at the end of a soliloquy. Plautus does this for dramatic effect to emphasize a point.

Further interwoven into the plays of Plautus and just as common as the use of proverbs is the use of Greek within the texts of the plays. J. N. Hough suggests that Plautus’s use of Greek is for artistic purposes and not simply because a Latin phrase will not fit the meter. Greek words are used when describing foods, oils, perfumes, etc. This is similar to the use of French terms in the English language such as garçon or rendezvous. These words give the language a French flair just as Greek did to the Latin-speaking Romans. Slaves or characters of low standing speak much of the Greek. One possible explanation for this is that many Roman slaves were foreigners of Greek origin.

Poetic Devices