Lessico

Lucilio

Gaius Lucilius

Poeta

satirico latino (Sessa Aurunca![]() , Caserta ca. 180 - Napoli ca. 102 aC). Di famiglia

facoltosa, dopo il 160 si trasferì a Roma, dove strinse amicizia con le

maggiori personalità della politica e della cultura. Fu intimo di Scipione

Emiliano, partecipò al suo circolo e militò con lui in Spagna, all'assedio

di Numanzia, nel 134-133.

, Caserta ca. 180 - Napoli ca. 102 aC). Di famiglia

facoltosa, dopo il 160 si trasferì a Roma, dove strinse amicizia con le

maggiori personalità della politica e della cultura. Fu intimo di Scipione

Emiliano, partecipò al suo circolo e militò con lui in Spagna, all'assedio

di Numanzia, nel 134-133.

Al suo ritorno a Roma, iniziò la sua opera poetica e accrebbe il numero dei suoi amici come dei suoi nemici (tra questi soprattutto notevoli Metello Macedonico e Muzio Scevola Augure). Nel 105 si ritirò a Napoli. La sua produzione poetica comprendeva 30 libri di satire, che furono raggruppate più tardi non secondo l'ordine cronologico della loro composizione, ma secondo l'evoluzione dei metri: così i libri 26-30 furono i primi a essere composti e pubblicati in un volume, verso il 124 aC, con metrica varia; i libri 1-21 furono invece pubblicati in un secondo volume verso il 106 aC, in esametri, e i libri 22-25 più tardi.

Di tutta l'opera rimangono solamente ca. 1300 versi, dai quali esce il ritratto di un uomo di grande apertura mentale, che osserva e critica la società romana, nel momento delle sue grandi conquiste in tutto il Mediterraneo, per gli eccessi dell'avidità, della ricchezza, degli scompensi tra le classi sociali. Il suo è l'atteggiamento liberale del circolo scipionico, con quel tanto di conservatorismo che è inevitabilmente proprio di ogni poeta satirico.

Questi

interessi moralistici prevalgono in Lucilio sulla cura artistica: egli non si

preoccupa molto dell'eleganza formale dell'esposizione e in versi esprime

anche polemiche letterarie, appunti di viaggio, lettere ad amici, nozioni di

linguistica. I giudizi dei successori furono quindi assai vari: si apprezzò

da alcuni la sua forza nel fustigare e denunciare i vizi della città, la sua

cultura, la sua franchezza, il suo spirito; altri, come Orazio![]() ,

ne criticarono soprattutto lo stile informe, poco elegante. Ma bisogna

ricordare che Lucilio inaugurò un genere letterario nuovo a Roma, dando tono

satirico a quel componimento poetico molto diverso che era stata fino ad

allora la satura romana.

,

ne criticarono soprattutto lo stile informe, poco elegante. Ma bisogna

ricordare che Lucilio inaugurò un genere letterario nuovo a Roma, dando tono

satirico a quel componimento poetico molto diverso che era stata fino ad

allora la satura romana.

Se

vogliamo un esempio della sua vena satirica ecco cosa scrisse circa l'inchiappettamento

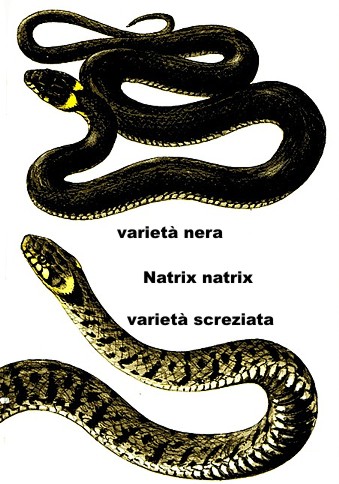

usando la biscia d'acqua, Natrix natrix![]() , in senso traslato per indicare

il pene

, in senso traslato per indicare

il pene![]() :

:

Si

natibus natricem impressit crassam et capitatam.

Se conficcò nelle natiche una natrice grossa e dalla grande testa.

Etimologia e biologia di natrix

Il verbo latino no, io nuoto, è stato progressivamente sostituito da nato. In greco abbiamo néø da cui deriva nëchø: ambedue significano io nuoto. Natrix è un sostantivo latino per lo più femminile che deriva da natum, un supino di no mai utilizzato in letteratura, e ha come primo significato quello di biscia d'acqua, biscia che nuota. Per antonomasia questa biscia è la Natrix natrix, della famiglia Colubridi, detta anche biscia dal collare.

Comune in tutta Europa, nuota nelle raccolte d'acqua dolce di ogni tipo con un rapido e sinuoso movimento, mantenendo la testa leggermente sollevata dalla superficie; è altresì in grado di rimanere a lungo immersa in prossimità del fondo. Tuttavia la natrice trascorre la maggior parte del tempo sulla terraferma. Si ciba di pesciolini e rane ed è del tutto inoffensiva per l'uomo, malgrado la sua saliva sia tossica per alcuni piccoli animali. La lunghezza totale è di 1 metro nei maschi, nelle femmine di alcune sottospecie può raggiungere i 2 metri.

Gaio Lucilio

Gaio

Lucilio (latino: Gaius Lucilius; Sessa Aurunca, 180 aC circa –

Napoli, 103 aC) è stato un poeta latino. Della biografia la data di morte è

sicura, mentre quella di nascita è ricostruita a partire dalla discussione

sull'esattezza della datazione tramandataci da San Girolamo![]() ,

che fissa la morte di Lucilio all'età di 46 anni, da cui deriva una datazione

dell'anno di nascita eccessivamente posteriore, cioè l'anno 149 aC, in

contrasto con una notizia fornitaci dallo storico Velleio Patercolo, in base

alla quale Lucilio aveva militato come cavaliere sotto Scipione Emiliano nella

guerra di Numanzia nel 133 aC.

,

che fissa la morte di Lucilio all'età di 46 anni, da cui deriva una datazione

dell'anno di nascita eccessivamente posteriore, cioè l'anno 149 aC, in

contrasto con una notizia fornitaci dallo storico Velleio Patercolo, in base

alla quale Lucilio aveva militato come cavaliere sotto Scipione Emiliano nella

guerra di Numanzia nel 133 aC.

Probabilmente l'errore di San Girolamo è stato di aver scambiato Sp. Postumio Albino e L. Calpurnio Pisone, consoli dell'anno 148 aC, con quelli del 180 aC, A. Postumio Albino e C. Calpurnio Pisone.

Le incertezze cronologiche relative alla sua vita non intaccano però l'aspetto fondamentale della sua biografia, dalla quale si capisce come il poeta fu vicino al circolo degli Scipioni e che fu amico intimo di Scipione Emiliano e di Gaio Lelio, due tra i maggiori promotori dell'ellenizzazione della cultura romana. Nonostante la sua posizione e le sue amicizie, si tenne sempre lontano dalla carriera politica, dedicandosi interamente all'otium letterario. Ciò non toglie che Lucilio fosse un personaggio molto influente: infatti, quando morì fu onorato con un funerale pubblico. L'importanza di Lucilio è enorme in relazione ai suoi sforzi per codificare sul piano formale (tramite l'uso dell'esametro), dello stile e del contenuto, i temi trattati dall'unico genere letterario latino mancante di un corrispondente nel mondo ellenico: la satira.

Dei 30

libri di satire scritti da Lucilio ci rimangono circa 1000 frammenti, per un

totale di quasi 1370 versi. La divisione in 30 libri del corpus luciliano è

puramente putativa e a opera del neotero Valerio Catone.

La parola satira non è di Lucilio (definizione apocrifa): quando ne

parla la definisce come schedía (in greco, fatta con

improvvisazione) o come poemata (poemi) o come sermones

(discussioni). I caratteri fondamentali della satira luciliana sono:

-

soggettivismo: Lucilio parla di sé stesso e inserisce contenuti

autobiografici

- spontaneità: parla con immediatezza e l'elaborazione letteraria è relativa

- aggressività: spesso ad personam, è una letteratura abrasiva

- eticità: Lucilio intende promuovere una modificazione comportamentale, ha

un fine educativo

- varietas

- plurilinguismo e ibridazione stilistica: non è né anodino né monocorde,

percorre tutte le possibilità della lingua latina, dal sermo plebeius

sino alle regioni più illustri della letteratura, ha uno stile

caleidoscopico.

L'opera di

Lucilio è fondamentale, perché sviluppa il concetto di satira (anche se non

la chiama così), genere basilare della cultura occidentale. Anche se si

ritiene fosse stato Ennio![]() a usare

per primo questo genere tipicamente romano, egli ne stilò lo statuto, poi

seguito dai successivi autori di satire, attraverso la sua opera

caratterizzata dal metro esametrico e dall'argomento morale. La satira del

mondo latino, dal punto di vista dei contenuti, vista la sua originalità

romana dal punto di vista formale, non ha nulla a che vedere con quella del

mondo greco, perché lì era sottopertinente al genere del giambo. L'obiezione

mossa alla lingua luciliana era di essere ruvida, provvisoria e incondita.

a usare

per primo questo genere tipicamente romano, egli ne stilò lo statuto, poi

seguito dai successivi autori di satire, attraverso la sua opera

caratterizzata dal metro esametrico e dall'argomento morale. La satira del

mondo latino, dal punto di vista dei contenuti, vista la sua originalità

romana dal punto di vista formale, non ha nulla a che vedere con quella del

mondo greco, perché lì era sottopertinente al genere del giambo. L'obiezione

mossa alla lingua luciliana era di essere ruvida, provvisoria e incondita.

« Faceva

mille versi stando su un piede solo »

Orazio

Gaius Lucilius (c. 180 BC - 103 BC), the earliest Roman satirist, of whose writings only fragments remain, was born at Suessa Aurunca in Campania. The dates assigned by Jerome for his birth and death are 148 BC and 103 BC or 102 BC. But it is impossible to reconcile the first of these dates with other facts recorded of him, and the date given by Jerome must be due to an error, the true date being about 180 BC.

We learn from Velleius Paterculus that he served under Scipio Aemilianus at the siege of Numantia in 134. We learn from Horace that he lived on the most intimate terms of friendship with Scipio and Laelius, and that he celebrated the exploits and virtues of the former in his satires.

Fragments of those books of his satires which seem to have been first given to the world (books xxvi.-xxix.) clearly indicate that they were written in the lifetime of Scipio. Some of these bring the poet before us as either corresponding with, or engaged in controversial conversation with, his great friend. 621 Marx, "Percrepa pugnam Popilli, facta Corneli cane" ("Make a loud noise about Popillius' battle, and sing the exploits of Cornelius") in which the defeat of Marcus Popillius Laenas, in 138 BC, is contrasted with the subsequent success of Scipio, bears the stamp of having been written while the news of the capture of Numantia was still fresh.

It is in the highest degree improbable that Lucilius served in the army at the age of fourteen; it is still more unlikely that he could have been admitted into the familiar intimacy of Scipio and Laelius at that age. It also seems an impossibility that between the ages of fifteen and nineteen--i.e. between 133 BC and 129 BC, the year of Scipio's death -- he could have come before the world as the author of an entirely new kind of composition, and one which, to be at all successful, demands especially maturity of judgment and experience.

It may further be said that the well-known words of Horace (Satires, ii. 1, 33), in which he characterizes the vivid portraiture of his life, character and thoughts, which Lucilius bequeathed to the world, "quo fit ut omnis Votiva pateat veluti descripta tabella Vita senis," ("Whereby the whole life of the old (great) man may be laid out as upon a votive tablet") lose much of their force unless senis is to be taken in its ordinary sense -- which it cannot be if Lucilius died at the age of forty-six.

Lucilius spent the greater part of his life at Rome, and died, according to Jerome, at Naples. He belonged to the equestrian order, a fact indicated by Horace's notice of himself as infra Lucili censum. Though not himself belonging to any of the great senatorial families, he was in a position to associate with them on equal terms. This circumstance contributed to the boldness, originality and thoroughly national character of his literary work. Had he been a semi-Graecus, like Ennius and Pacuvius, or of humble origin, like Plautus, Terence or Accius, he would scarcely have ventured, at a time when the senatorial power was strongly in the ascendant, to revive the rôle which had proved disastrous to Naevius; nor would he have had the intimate knowledge of the political and social life of his day which fitted him to be its painter. Another circumstance determining the bent of his mind was the character of the time. The origin of Roman political and social satire is to be traced to the same disturbing and disorganizing forces which led to the revolutionary projects and legislation of the Gracchi.

The reputation which Lucilius enjoyed in the best ages of Roman literature is proved by the terms in which Cicero and Horace speak of him. Persius, Juvenal and Quintilian vouch for the admiration with which he was regarded in the first century of the empire. The popularity which he enjoyed in his own time is attested by the fact that at his death, although he had filled none of the offices of state, he received the honour of a public funeral. His chief claim to distinction is his literary originality. He may be called the inventor of poetical satire, as he was the first to impress upon the rude inartistic medley, known to the Romans by the name of satura, that character of aggressive and censorious criticism of persons, morals, manners, politics, literature, etc. which the word satire has ever since denoted.

In point of form the satire of Lucilius owed nothing to the Greeks. It was a legitimate development of an indigenous dramatic entertainment, popular among the Romans before the first introduction of the forms of Greek art among them; and it seems largely also to have employed the form of the familiar epistle. But the style, substance and spirit of his writings were apparently as original as the form. He seems to have commenced his poetical career by ridiculing and parodying the conventional language of epic and tragic poetry, and to have used the language commonly employed in the social intercourse of educated men. Even his frequent use of Greek words, phrases and quotations, reprehended by Horace, was probably taken from the actual practice of men, who found their own speech as yet inadequate to give free expression to the new ideas and impressions which they derived from their first contact with Greek philosophy, rhetoric and poetry.

Further, he not only created a style of his own, but, instead of taking the substance of his writings from Greek poetry, or from a remote past, he treated of the familiar matters of daily life, of the politics, the wars, the administration of justice, the eating and drinking, the money-making and money-spending, the scandals and vices, which made up the public and private life of Rome in the last quarter of the 2nd century BC. This he did in a singularly frank, independent and courageous spirit, with no private ambition to serve, or party cause to advance, but with an honest desire to expose the iniquity or incompetence of the governing body, the sordid aims of the middle class, and the corruption and venality of the city mob. There was nothing of stoical austerity or of rhetorical indignation in the tone in which he treated the vices and follies of his time.

His character and tastes were much more akin to those of Horace than of either Persius or Juvenal. But he was what Horace was not, a thoroughly good hater; and he lived at a time when the utmost freedom of speech and the most unrestrained indulgence of public and private animosity were the characteristics of men who took a prominent part in affairs. Although Lucilius took no active part in the public life of his time, he regarded it in the spirit of a man of the world and of society, as well as a man of letters. His ideal of public virtue and private worth had been formed by intimate association with the greatest and best of the soldiers and statesmen of an older generation.

The remains of Lucilius extend to about eleven hundred, mostly unconnected lines, most of them preserved by late grammarians, as illustrative of peculiar verbal usages. He was, for his time, a voluminous as well as a very discursive writer. He left behind him thirty books of satires, and there is reason to believe that each book, like the books of Horace and Juvenal, was composed of different pieces. The order in which they were known to the grammarians was not that in which they were written. The earliest in order of composition were probably those numbered from xxvi. to xxix., which were written in the trochaic and iambic metres that had been employed by Ennius and Pacuvius in their Saturae.

In these he made those criticisms on the older tragic and epic poets of which Horace and other ancient writers speak. In them too he speaks of the Numantine War as recently finished, and of Scipio as still living. Book i., on the other hand, in which the philosopher Carneades, who died in 128, is spoken of as dead, must have been written after the death of Scipio.

Most of the satires of Lucilius were written in hexameters, but, so far as an opinion can be formed from a number of unconnected fragments, he seems to have written the trochaic tetrameter with a smoothness, clearness and simplicity which he never attained in handling the hexameter. The longer fragments produce the impression of great discursiveness and carelessness, but at the same time of considerable force. He appears, in the composition of his various pieces, to have treated everything that occurred to him in the most desultory fashion, sometimes adopting the form of dialogue, sometimes that of an epistle or an imaginary discourse, and often to have spoken in his own name, giving an account of his travels and adventures, or of amusing scenes that he had witnessed, or expressing the results of his private meditation and experiences.

Like Horace he largely illustrated his own observations by personal anecdotes and fables. The fragments clearly show how often Horace has imitated him, not only in expression, but in the form of his satires (see for instance i. 5 and ii. 2), in the topic which he treats of, and the class of social vices and the types of character which he satirizes.