Lessico

Ecate

In

greco Ἑκάτη, in latino Hecate. Dea

greca in cui si realizzava l'alterità, la differenza, rispetto agli uomini e

agli dei stessi: era una titanessa, figlia di Asteria, contrapposta agli dei

veri e propri, subentrati ai Titani![]() nel dominio

dell'universo. Zeus

nel dominio

dell'universo. Zeus![]() le aveva concesso di

conservare tutto il suo antico potere. Un altro mito la dice figlia di Notte

le aveva concesso di

conservare tutto il suo antico potere. Un altro mito la dice figlia di Notte![]() , e allora la sua

tenebrosità veniva opposta alla luminosità degli dei. A differenza degli

dei, che avevano ciascuno uno specifico campo d'azione, Ecate estendeva il suo

potere in ogni campo. Invocata nei parti, proteggeva ogni altro

“passaggio” (le porte e le strade, dove era venerata con immagini

triformi) e presiedeva alle attività magiche. Fu identificata con Artemide

, e allora la sua

tenebrosità veniva opposta alla luminosità degli dei. A differenza degli

dei, che avevano ciascuno uno specifico campo d'azione, Ecate estendeva il suo

potere in ogni campo. Invocata nei parti, proteggeva ogni altro

“passaggio” (le porte e le strade, dove era venerata con immagini

triformi) e presiedeva alle attività magiche. Fu identificata con Artemide![]() , la cui azione si

svolgeva in un'alterità limitata, e con Persefone

, la cui azione si

svolgeva in un'alterità limitata, e con Persefone![]() , la dea dei morti (gli

altri rispetto ai vivi). Rappresentata in un primo tempo con lunga veste e

fiaccole nelle mani, fu poi raffigurata nel suo caratteristico aspetto

trimorfo, come dea del cielo, della terra e dell'oltretomba, con

un'innovazione dovuta allo scultore Alcamene attivo alla fine del sec. V aC e

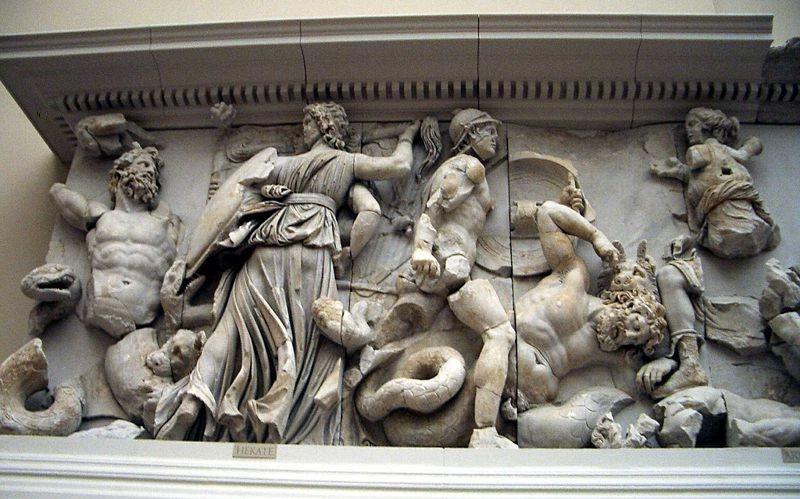

allievo di Fidia (statua di Ecate sull'Acropoli di Atene). Nell'ara di Pergamo

è rappresentata con un corpo solo, ma con tre teste e sei braccia. Le fonti

ricordano a Egina una Ecate di Mirone e nel tempio di Ilizia ad Argo statue di

Scopa, Policleto il Giovane e Naucide.

, la dea dei morti (gli

altri rispetto ai vivi). Rappresentata in un primo tempo con lunga veste e

fiaccole nelle mani, fu poi raffigurata nel suo caratteristico aspetto

trimorfo, come dea del cielo, della terra e dell'oltretomba, con

un'innovazione dovuta allo scultore Alcamene attivo alla fine del sec. V aC e

allievo di Fidia (statua di Ecate sull'Acropoli di Atene). Nell'ara di Pergamo

è rappresentata con un corpo solo, ma con tre teste e sei braccia. Le fonti

ricordano a Egina una Ecate di Mirone e nel tempio di Ilizia ad Argo statue di

Scopa, Policleto il Giovane e Naucide.

Ecate

La

Ecate Chiaramonti, una scultura romana della triplice Ecate,

successiva a un originale Ellenistico,

Città del Vaticano - Museo Chiaramonti - Musei Vaticani

Ecate è una dea della religione greca e romana (lat. Hecata o Hecate), ma di origine pre-indoeuropea. Ecate era una divinità psicopompa - una figura (in genere una divinità) che svolge la funzione di accompagnare le anime dei morti nell'oltretomba - in grado di viaggiare liberamente tra il mondo degli uomini, quello degli Dei e il regno dei Morti. Spesso è raffigurata con delle torce in mano, proprio per questa sua capacità di accompagnare anche i vivi nel regno dei morti (la Sibilla Cumana, a lei consacrata, traeva da Ecate la capacità di dare responsi provenienti, appunto, dagli spiriti o dagli Dei). Le sue figlie erano chiamate empuse.

Dea degli incantesimi e degli spettri, Ecate è raffigurata come triplice (giovane, adulta/madre e vecchia), e il numero Tre la rappresenta; le sue statue venivano poste negli incroci (trivi), a protezione dei viandanti (Ecate Enodia o Ecate Trioditis). Le sue origini sono poco note: Esiodo la ritiene figlia del titano Persete e di Asteria, e quindi è discendente diretta della stirpe titanica. Ma un'altra tradizione la riconosce come la figlia di Zeus e di una figlia di Eolo, chiamata Ferea. Fu Ecate a sentire le grida disperate di Persefone, rapita da Ade presso il Lago Pergusa e portata negli Inferi, e fu sempre lei ad avvertire Demetra di quanto era accaduto. Ecate veniva anche associata in alcuni casi ai cicli lunari, insieme ad altre divinità come Diana/Artemide, e Selene, a simboleggiare la luna calante.

Nell'iconografia Ecate viene rappresentata spesso con tre corpi o con sembianze di cane, o accompagnata da cani infernali ululanti in quanto veniva considerata protettrice dei cani. Un altro animale sacro a tale divinità era la colomba. La natura di Ecate è bi-sessuata, in quanto possiede in sé entrambi i principi della generazione, il maschile e il femminile. Per questo motivo viene definita la fonte della vita e le viene attribuito il potere vitale su tutti gli elementi.

Hecate, Hekate (Hekátē), o Hekat fu in origine una dea delle terre selvagge e del parto proveniente dalla Tracia, o dai cariani dell'Anatolia. I culti popolari che la veneravano come una dea madre inserirono la sua persona nella cultura greca come Ἑκάτη. Nell'Alessandria tolemaica essa in ultima analisi ottenne le sue connotazioni di dea della stregoneria e il suo ruolo di Regina degli Spettri, in queste vesti fu poi trasmessa alla cultura post-rinascimentale. Oggi è vista spesso come una dea delle arti magiche e della Stregoneria. È inoltre l'equivalente della Trivia romana.

Ecate

o le tre Parche

William Blake 1795 - Londra

Le prime rappresentazioni di Ecate sono singole e non triplici. Lewis Richard Farnell sostiene che la testimonianza lasciata dai monumenti sulle caratteristiche e il significato di Ecate è altrettanto ricca di quella trasmessa dalla letteratura, ma solo nel periodo più tardo essi esprimono la sua natura molteplice e mistica. Prima del quinto secolo è quasi certo che fosse spesso rappresentata come una singola forma, come ogni altra divinità, ed è così che la immaginò Esiodo, perché nulla nei suoi versi allude a una divinità dalla triplice forma. Il monumento più antico è una piccola terracotta trovata ad Atene, con una dedica a Ecate (tavola XXXVIII. a), in una scrittura tipica del sesto secolo. La dea è seduta su un trono e ha una corona attorno alla testa; non ha nessun tratto o caratteristica distintivi e l'unico valore dell'opera, che è chiaramente di un tipo comune ed è degna di menzione solo per l'iscrizione, è che prova come la forma singola fosse quella originale e che ad Atene era conosciuta prima dell'invasione persiana.

Ecate

combatte Clitio, a sinistra.

Dettaglio del Rilievo dall'Altare di Pergamo, IV secolo aC.

Pausania

il Periegeta![]() sosteneva che Ecate fosse stata dipinta per la prima volta nella forma

triplice dallo scultore Alcamene durante il periodo greco classico, verso la

fine del quinto secolo. Alcuni ritratti classici mostrano la dea in forma

triplice mentre regge una torcia, una chiave e un serpente. Altri continuano a

rappresentarla in forma singola. Negli scritti esoterici in greco, di

derivazione egiziana, con riferimento a Ermete Trismegisto e nei papiri di

magia della Tarda Antichità è descritta come una creatura a tre teste: una

di cane, una di serpente e una di cavallo. La triplicità di Ecate è espressa

in una forma più ellenica, con tre corpi, mentre prende parte alla battaglia

contro i titani nel vasto fregio del grande altare di Pergamo, ora a Berlino.

Ad Argolide, vicino al sacrario dei Dioscuri, Pausania, grande viaggiatore nel

corso del secondo secolo dell'era cristiana, vide il tempio di Ecate davanti

al santuario di Ilizia: L'immagine è opera di Scopas, realizzata in pietra,

mentre le immagini in bronzo che si trovano davanti, che hanno come soggetto

sempre Ecate, furono realizzate rispettivamente da Policleto e suo fratello

Naucide, figlio di Motone. (Periegesi

della Grecia

ii.22.7)

sosteneva che Ecate fosse stata dipinta per la prima volta nella forma

triplice dallo scultore Alcamene durante il periodo greco classico, verso la

fine del quinto secolo. Alcuni ritratti classici mostrano la dea in forma

triplice mentre regge una torcia, una chiave e un serpente. Altri continuano a

rappresentarla in forma singola. Negli scritti esoterici in greco, di

derivazione egiziana, con riferimento a Ermete Trismegisto e nei papiri di

magia della Tarda Antichità è descritta come una creatura a tre teste: una

di cane, una di serpente e una di cavallo. La triplicità di Ecate è espressa

in una forma più ellenica, con tre corpi, mentre prende parte alla battaglia

contro i titani nel vasto fregio del grande altare di Pergamo, ora a Berlino.

Ad Argolide, vicino al sacrario dei Dioscuri, Pausania, grande viaggiatore nel

corso del secondo secolo dell'era cristiana, vide il tempio di Ecate davanti

al santuario di Ilizia: L'immagine è opera di Scopas, realizzata in pietra,

mentre le immagini in bronzo che si trovano davanti, che hanno come soggetto

sempre Ecate, furono realizzate rispettivamente da Policleto e suo fratello

Naucide, figlio di Motone. (Periegesi

della Grecia

ii.22.7)

Un rilievo in marmo del IV secolo d.C. di Crannone in Tessaglia recava una dedica di un proprietario di cavalli. Il rilievo mostrava Ecate, in compagnia di un cane, mentre posa un serto sul capo di una cavalla. Questa statua si trova nel British Museum, inventario n° 816. La cagna è la sua compagna e il suo equivalente animale e una delle forme più usuali di offerte era lasciare della carne ai crocicchi. A volte gli stessi cani le venivano sacrificati (un giusto accenno alle sue origini non elleniche, dato che i cani, insieme agli asini, raramente venivano tenuti in così alta considerazione negli antichi rituali greci).

The

Hecate Chiaramonti, a Roman sculpture of triple Hecate,

after a Hellenistic original (Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums).

Hecate or Hekate (ancient Greek Ἑκάτη, Hekátē) is a chthonic Greco-Roman goddess associated with magic, witches, ghosts, and crossroads. She is attested in poetry as early as Hesiod's Theogony. An inscription from late archaic Miletus naming her as a protector of entrances is also testimony to her presence in archaic Greek religion. Regarding the nature of her cult, it has been remarked, "she is more at home on the fringes than in the center of Greek polytheism. Intrinsically ambivalent and polymorphous, she straddles conventional boundaries and eludes definition." She has been associated with childbirth, nurturing the young, gates and walls, doorways, crossroads, magic, lunar lore, torches and dogs. William Berg observes, "Since children are not called after spooks, it is safe to assume that Carian theophoric names involving hekat - refer to a major deity free from the dark and unsavoury ties to the underworld and to witchcraft associated with the Hecate of classical Athens." But he cautions, "The Laginetan goddess may have had a more infernal character than scholars have been willing to assume." In Ptolemaic Alexandria and elsewhere during the Hellenistic period, she appears as a three-faced goddess associated with ghosts, witchcraft, and curses. Today she is claimed as a goddess of witches and in the context of Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism. Some neo-pagans refer to her as a "crone goddess", though this characterization appears to conflict with her frequent characterization as a virgin in late antiquity. She closely parallels the Roman goddess Trivia.

Notable proposed

etymologies for the name Hecate are:

A) From Greek Ἑκάτη [Hekátē],

feminine equivalent of Hekatos, obscure epithet of Apollo.

B) A native name meaning 'far-shooting' or 'far darter' based on ἑκάς 'far'.

C) From the Greek word for 'will'.

D) From the Egyptian goddess of childbirth, Heqet.

Arthur Golding's 1567 translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses refers to "triple Hecat" and this spelling without the final E later appears in plays of the Elizabethan-Jacobean period. Noah Webster in 1866 particularly credits the influence of Shakespeare for the then-predominant pronunciation of "Hecate" without the final E. The earliest Greek depictions of Hecate are single faced, not triplicate. Lewis Richard Farnell states: "The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hecate is almost as full as that of the literature. But it is only in the later period that they come to express her manifold and mystic nature. Before the fifth century there is little doubt that she was usually represented as of single form like any other divinity, and it was thus that the Boeotian poet imagined her, as nothing in his verses contains any allusion to a triple formed goddess."

Triple

Hecate and the Charites, Attic,

3rd century BCE (Glyptothek, Munich).

The earliest known monument is a small terracotta found in Athens, with a dedication to Hecate, in writing of the style of the sixth century. The goddess is seated on a throne with a chaplet bound round her head; she is altogether without attributes and character, and the only value of this work, which is evidently of quite a general type and gets a special reference and name merely from the inscription, is that it proves the single shape to be her earlier form, and her recognition at Athens to be earlier than the Persian invasion.

The second-century traveller Pausanias stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor Alkamenes in the Greek Classical period of the late fifth century. Greek anthropomorphic conventions of art resisted representing her with three faces: a votive sculpture from Attica of the third century BCE, shows three single images against a column; round the column of Hecate dance the Charites. Some classical portrayals show her as a triplicate goddess holding a torch, a key, and a serpent. Others continue to depict her in singular form.

In Egyptian-inspired Greek esoteric writings connected with Hermes Trismegistus, and in magical papyri of Late Antiquity she is described as having three heads: one dog, one serpent, and one horse. In other representations her animal heads include those of a cow and a boar. Hecate's triplicity is elsewhere expressed in a more Hellenic fashion in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, now in Berlin, wherein she is shown with three bodies, taking part in the battle with the Titans. In the Argolid, near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias saw the temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eileithyia. He reported the image to be the work of Scopas, stating further, "This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hecate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon." (Description of Greece 2.22.7)

A fourth century BCE

marble relief from Crannon in Thessaly was dedicated by a race-horse owner. It

shows Hecate, with a hound beside her, placing a wreath on the head of a mare.

She is commonly attended by a dog or dogs, and the most common form of

offering was to leave meat at a crossroads. Sometimes dogs themselves were

sacrificed to her. This is sometimes offered as an indication of her

non-Hellenic origin, as dogs very rarely played this role in genuine Greek

ritual.

In the Argonautica, a third century BCE Alexandrian epic based on early

materials, Jason placates Hecate in a ritual prescribed by Medea, her

priestess: bathed at midnight in a stream of flowing water, and dressed in

dark robes, Jason is to dig a pit and offer a libation of honey and blood from

the throat of a sheep, which was set on a pyre by the pit and wholly consumed

as a holocaust, then retreat from the site without looking back (Argonautica,

3). All these elements betoken the rites owed to a chthonic deity.

Hecate has been characterized as a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess. She appears in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and in Hesiod's Theogony, where she is promoted strongly as a great goddess. The place of origin of her following is uncertain, but it is thought that she had popular followings in Thrace. Her most important sanctuary was Lagina, a theocratic city-state in which the goddess was served by eunuchs. Lagina, where the famous temple of Hecate drew great festal assemblies every year, lay close to the originally Macedonian colony of Stratonikeia, where she was the city's patroness. In Thrace she played a role similar to that of lesser-Hermes, namely a governess of liminal regions (particularly gates) and the wilderness, bearing little resemblance to the night-walking crone she became. Additionally, this led to her role of aiding women in childbirth and the raising of young men.

Hecate,

Greek goddess of the crossroads; drawing by Stephane Mallarmé

in Les Dieux Antiques, nouvelle mythologie illustrée in Paris, 1880.

Hesiod records that she was among the offspring of Gaia and Uranus, the Earth and Sky. In Theogony he ascribed great powers to Hecate: [...] Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honor also in starry heaven, and is honored exceedingly by the deathless gods. For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favor according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honor comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favorably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her. For as many as were born of Earth and Ocean amongst all these she has her due portion. The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea.

According to Hesiod, she held sway over many things: Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgement, and in the assembly whom she will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker, easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less. So, then, albeit her mother's only child, she is honored amongst all the deathless gods. And the son of Cronos made her a nurse of the young who after that day saw with their eyes the light of all-seeing Dawn. So from the beginning she is a nurse of the young, and these are her honors.

Hesiod emphasizes that Hecate was an only child, the daughter of Perses and Asteria, a star-goddess who was the sister of Leto (the mother of Artemis and Apollo). Grandmother of the three cousins was Phoebe the ancient Titaness who personified the moon.

Hesiod's inclusion and praise of Hecate in the Theogony has been troublesome for scholars, in that he seems to hold her in high regard, while the testimony of other writers, and surviving evidence, suggests that this was probably somewhat exceptional. It is theorized that Hesiod’s original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was a way of adding to her prestige by spreading word of her among his readers.

Hecate possibly originated among the Carians of Anatolia, the region where most theophoric names invoking Hecate, such as Hecataeus or Hecatomnus, the father of Mausolus, are attested, and where Hecate remained a Great Goddess into historical times, at her unrivalled cult site in Lagina. While many researchers favor the idea that she has Anatolian origins, it has been argued that "Hecate must have been a Greek goddess." The monuments to Hecate in Phrygia and Caria are numerous but of late date.

If Hecate's cult spread from Anatolia into Greece, it is possible it presented a conflict, as her role was already filled by other more prominent deities in the Greek pantheon, above all by Artemis and Selene. This line of reasoning lies behind the widely accepted hypothesis that she was a foreign deity who was incorporated into the Greek pantheon. Other than in the Theogony, the Greek sources do not offer a consistent story of her parentage, or of her relations in the Greek pantheon: sometimes Hecate is related as a Titaness, and a mighty helper and protector of humans. Her continued presence was explained by asserting that, because she was the only Titan who aided Zeus in the battle of gods and Titans, she was not banished into the underworld realms after their defeat by the Olympians.

One surviving group of stories suggests how Hecate might have come to be incorporated into the Greek pantheon without affecting the privileged position of Artemis. Here, Hecate is a mortal priestess often associated with Iphigeneia. She scorns and insults Artemis, who in retribution eventually brings about the mortal's suicide. Artemis then adorns the dead body with jewelry and commands the spirit to rise and become her Hecate, who subsequently performs a role similar to Nemesis as an avenging spirit, but solely for injured women. Such myths in which a native deity 'sponsors' or ‘creates’ a foreign one were widespread in ancient cultures as a way of integrating foreign cults. If this interpretation is correct, as Hecate’s cult grew, she was inserted into the later myth of the birth of Zeus as one of the midwives that hid the child, while Cronus consumed the deceiving rock handed to him by Gaia. There was an area sacred to Hecate in the precincts of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, where the priests, megabyzi, officiated.

Hecate also came to be associated with ghosts, infernal spirits, the dead and sorcery. Like the totems of Hermes — herms placed at borders as a ward against danger — images of Hecate (like Artemis and Diana, often referred to as a "liminal" goddess) were also placed at the gates of cities, and eventually domestic doorways. Over time, the association with keeping out evil spirits could have led to the belief that if offended, Hecate could also allow the evil spirits in. According to one view, this accounts for invocations to Hecate as the supreme governess of the borders between the normal world and the spirit world, and hence as one with mastery over spirits of the dead. Whatever the reasons, Hecate’s power certainly came to be closely associated with sorcery. One interesting passage exists suggesting that the word "jinx" might have originated in a cult object associated with Hecate. "The Byzantine polymath Michael Psellus [...] speaks of a bullroarer, consisting of a golden sphere, decorated throughout with symbols and whirled on an oxhide thong. He adds that such an instrument is called a iunx (hence "jinx"), but as for the significance says only that it is ineffable and that the ritual is sacred to Hecate."

Hecate is one of the most important figures in the so-called Chaldaean Oracles (2nd-3rd century CE), where she is associated in fragment 194 with a strophalos (usually translated as a spinning top, or wheel, used in magic) "Labour thou around the Strophalos of Hecate." This appears to refer to a variant of the device mentioned by Psellus.

Variations in interpretations of Hecate's role or roles can be traced in fifth-century Athens. In two fragments of Aeschylus she appears as a great goddess. In Sophocles and Euripides she is characterized as the mistress of witchcraft and the Keres. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Hecate is called the "tender-hearted", a euphemism perhaps intended to emphasize her concern with the disappearance of Persephone, when she addressed Demeter with sweet words at a time when the goddess was distressed. She later became Persephone's minister and close companion in the Underworld. But Hecate was never fully incorporated among the Olympian deities.

The modern understanding of Hecate has been strongly influenced by syncretic Hellenistic interpretations. Many of the attributes she was assigned in this period appear to have an older basis. For example, in the magical papyri of Ptolemaic Egypt, she is called the 'she-dog' or 'bitch', and her presence is signified by the barking of dogs. In late imagery she also has two ghostly dogs as servants by her side. However, her association with dogs predates the conquests of Alexander the Great and the emergence of the Hellenistic world. When Philip II laid siege to Byzantium she had already been associated with dogs for some time; the light in the sky and the barking of dogs that warned the citizens of a night time attack, saving the city, were attributed to Hecate Lampadephoros (the tale is preserved in the Suda). In gratitude the Byzantines erected a statue in her honor.

As a virgin goddess, she

remained unmarried and had no regular consort, though some traditions named

her as the mother of Scylla. Other names and epithets

Chthonia (of the earth/underworld)

Apotropaia (that turns away/protects)

Enodia (on the way)

Kourotrophos (nurse of children)

Propulaia/Propylaia (before the gate)

Propolos (who serves/attends)

Phosphoros (bringing or giving light)

Soteira (savior)

Triodia/Trioditis (who frequents crossroads)

Klêidouchos (holding the keys)

Trimorphe (three-formed)

Goddess of the crossroads - Cult images and altars of Hecate in her triplicate or trimorphic form were placed at crossroads (though they also appeared before private homes and in front of city gates). In this form she came to be known as the goddess Trivia "the three ways" in Roman mythology. In what appears to be a 7th Century indication of the survival of cult practices of this general sort, Saint Eligius, in his Sermo warns the sick among his recently converted flock in Flanders against putting "devilish charms at springs or trees or crossroads", and, according to Saint Ouen would urge them "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the deities of the trivium, where three roads meet...".

Dogs were closely associated with Hecate in the Classical world. "In art and in literature Hecate is constantly represented as dog-shaped or as accompanied by a dog. Her approach was heralded by the howling of a dog. The dog was Hecate's regular sacrificial animal, and was often eaten in solemn sacrament." The sacrifice of dogs to Hecate is attested for Thrace, Samothrace, Colophon, and Athens.

It has been claimed that her association with dogs is "suggestive of her connection with birth, for the dog was sacred to Eileithyia, Genetyllis, and other birth goddesses. Although in later times Hecate's dog came to be thought of as a manifestation of restless souls or demons who accompanied her, its docile appearance and its accompaniment of a Hecate who looks completely friendly in many pieces of ancient art suggests that its original signification was positive and thus likelier to have arisen from the dog's connection with birth than the dog's demonic associations."

thenaeus (writing in the 1st or 2nd century BCE, and drawing on the etymological speculation of Apollodorus) notes that the red mullet is sacred to Hecate, "on account of the resemblance of their names; for that the goddess is trimorphos, of a triple form". The Greek word for mullet was trigle and later trigla. He goes on to quote a fragment of verse "O mistress Hecate, Trioditis / With three forms and three faces / Propitiated with mullets". In relation to Greek concepts of pollution, Parker observes, "The fish that was most commonly banned was the red mullet (trigle), which fits neatly into the pattern. It 'delighted in polluted things,' and 'would eat the corpse of a fish or a man'. Blood-coloured itself, it was sacred to the blood-eating goddess Hecate. It seems a symbolic summation of all the negative characteristics of the creatures of the deep." At Athens, it is said there stood a statue of Hecate Triglathena, to whom the red mullet was offered in sacrifice. After mentioning that this fish was sacred to Hecate, Alan Davidson writes, "Cicero, Horace, Juvenal, Martial, Pliny, Seneca and Suetonius have left abundant and interesting testimony to the red mullet fever which began to affect wealthy Romans during the last years of the Republic and really gripped them in the early Empire. The main symptoms were a preoccupation with size, the consequent rise to absurd heights of the prices of large specimens, a habit of keeping red mullet in captivity, and the enjoyment of the highly specialized aesthetic experience induced by watching the color of the dying fish change." The frog, significantly a creature that can cross between two elements, also is sacred to Hecate. In her three-headed representations, discussed above, Hecate often has one or more animal heads, including cow, dog, boar, serpent and horse.

Hecate was closely associated with plant lore and the concoction of medicines and poisons. In particular she was thought to give instruction in these closely related arts. Apollonius of Rhodes, in the Argonautica mentions that Medea was taught by Hecate, "I have mentioned to you before a certain young girl whom Hecate, daughter of Perses, has taught to work in drugs." The goddess is described as wearing oak in fragments of Sophocles' lost play The Root Diggers (or The Root Cutters), and an ancient commentary on Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica (3.1214) describes her as having a head surrounded by serpents, twining through branches of oak.

The yew in particular was sacred to Hecate: "Greeks held the yew to be sacred to Hecate, queen of the underworld, crone aspect of the Triple Goddess. Her attendants draped wreathes of yew around the necks of black bulls which they slaughtered in her honor and yew boughs were burned on funeral pyres. The yew was associated with the alphabet and the scientific name for yew today, taxus, was probably derived from the Greek word for yew, toxos, which is hauntingly similar to toxon, their word for bow and toxicon, their word for poison. It is presumed that the latter were named after the tree because of its superiority for both bows and poison." Hecate was said to favor offerings of garlic, which was closely associated with her cult. She is also sometimes associated with cypress, a tree symbolic of death and the underworld, and hence sacred to a number of chthonic deities.

A number of other plants (often poisonous, medicinal and/or psychoactive) are associated with Hecate. These include aconite (also called hecateis), belladonna, dittany, and mandrake. It has been suggested that the use of dogs for digging up mandrake is further corroboration of the association of this plant with Hecate; indeed, since at least as early as the first century CE, there are a number of attestations to the apparently widespread practice of using dogs to dig up plants associated with magic.

Hecate was associated with borders, city walls, doorways, crossroads and, by extension, with realms outside or beyond the world of the living. She appears to have been particularly associated with being 'between' and hence is frequently characterized as a "liminal" goddess. "Hecate mediated between regimes - Olympian and Titan - but also between mortal and divine spheres." This liminal role is reflected in a number of her cult titles: Apotropaia (that turns away/protects); Enodia (on the way); Propulaia/Propylaia (before the gate); Triodia/Trioditis (who frequents crossroads); Klêidouchos (holding the keys), etc.

As a goddess expected to avert demons from the house or city over which she stood guard and to protect the individual as she or he passed through dangerous liminal places, Hecate would naturally become known as a goddess who could also refuse to avert the demons, or even drive them on against unfortunate individuals. It was probably her role as guardian of entrances that led to Hecate's identification by the mid fifth century with Enodia, a Thessalian goddess. Enodia's very name ("In-the-Road") suggests that she watched over entrances, for it expresses both the possibility that she stood on the main road into a city, keeping an eye on all who entered, and in the road in front of private houses, protecting their inhabitants.

This function would appear to have some relationship with the iconographic association of Hecate with keys, and might also relate to her appearance with two torches, which when positioned on either side of a gate or door illuminated the immediate area and allowed visitors to be identified. "In Byzantium small temples in her honor were placed close to the gates of the city. Hecate's importance to Byzantium was above all as a deity of protection. When Philip of Macedon was about to attack the city, according to the legend she alerted the townspeople with her ever present torches, and with her pack of dogs, which served as her constant companions." This suggests that Hecate's close association with dogs derived in part from the use of watchdogs, who, particularly at night, raised an alarm when intruders approached. Watchdogs were used extensively by Greeks and Romans. Like Hecate, "the dog is a creature of the threshold, the guardian of doors and portals, and so it is appropriately associated with the frontier between life and death, and with demons and ghosts which move across the frontier. The yawning gates of Hades were guarded by the monstrous watchdog Cerberus, whose function was to prevent the living from entering the underworld, and the dead from leaving it."

Hecate was worshipped by both the Greeks and the Romans who had their own festivals dedicated to her. According to Ruickbie (2004, p. 19) the Greeks observed two days sacred to Hecate, one on the 13th of August and one on the 30th of November, whilst the Romans observed the 29th of every month as her sacred day. Hecate has survived in folklore as a 'hag' figure associated with witchcraft. Strmiska notes that Hecate, conflated with the figure of Diana, appears in late antiquity and in the early medieval period as part of an "emerging legend complex" associated with gatherings of women, the moon, and witchcraft that eventually became established "in the area of Northern Italy, southern Germany, and the western Balkans." This theory of the Roman origins of many European folk traditions related to Diana or Hecate was explicitly advanced at least as early as 1807 and is reflected in numerous etymological claims by lexicographers from the 17th to the 19th century, deriving "hag" and/or "hex" from Hecate by way of haegtesse (Anglo-Saxon) and hagazussa (Old High German). Such derivations are today proposed only by a minority since being refuted by Grimm, who was skeptical of theories proposing non-Germanic origins for German folklore traditions. Modern etymology reconstructs Proto-Germanic *hagatusjon- from haegtesse and hagazussa; the first element is probably cognate with hedge, which derives from PIE *kagh- "hedge, enclosure", and the second perhaps from *dhewes- "fly about, be smoke, vanish."

Whatever the precise nature of Hecate's transition into folklore in late Antiquity, she is now firmly established as a figure in Neopaganism, which draws heavily on folkloric traditions associating Hecate with 'The Wild Hunt', hedges and 'hedge-riding', and other themes that parallel, but are not explicitly attested in, Classical sources.

The figure of Hecate can often be associated with the figure of Isis in Egyptian myth, mainly due to her role as sorceress. Both were symbols of liminal points. Lucius Apuleius (c. 123 - c. 170 CE) in his work "The Golden Ass" associates Hecate with Isis: "I am she that is the natural mother of all things, mistress and governess of all the elements, the initial progeny of worlds, chief of powers divine, Queen of heaven, the principal of the Gods celestial, the light of the goddesses: at my will the planets of the air, the wholesome winds of the Seas, and the silences of hell be disposed; my name, my divinity is adored throughout all the world in divers manners, in variable customs and in many names, [...] Some call me Juno, others Bellona of the Battles, and still others Hecate. Principally the Ethiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the Egyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustomed to worship me, do call me Queen Isis. [...]"

Some historians compare her to the Virgin Mary. She is also comparable to Hel of Nordic myth in her underworld function. Before she became associated with Greek mythology, she had many similarities with Artemis (wilderness, and watching over wedding ceremonies) and Hera (child rearing and the protection of young men or heroes, and watching over wedding ceremonies).