Lessico

Ades

/ Ade

Plutone

Busto

di Ade in marmo

copia romana di un originale greco del V secolo aC

Roma - Museo Nazionale Romano

Ades o Ade,

in greco Háidës o Hádës o in altri modi ancora, era il dio degli Inferi, figlio

di Crono![]() e

di Rea, fratello di Zeus

e

di Rea, fratello di Zeus![]() e di

Poseidone. Quando, cacciato Crono, i tre fratelli si divisero l'universo, a

Ades toccò il regno sotterraneo, donde il suo nome (probabilmente di origine

indoeuropea, col significato di occulto, invisibile). Poiché la sua residenza

era oscura e cupa, nessuna dea voleva sposarlo. Ma Ades s'invaghì della bella

Persefone

e di

Poseidone. Quando, cacciato Crono, i tre fratelli si divisero l'universo, a

Ades toccò il regno sotterraneo, donde il suo nome (probabilmente di origine

indoeuropea, col significato di occulto, invisibile). Poiché la sua residenza

era oscura e cupa, nessuna dea voleva sposarlo. Ma Ades s'invaghì della bella

Persefone![]() , figlia

di Demetra

, figlia

di Demetra![]() , la rapì

e la sposò, facendone la regina dell'Oltretomba.

, la rapì

e la sposò, facendone la regina dell'Oltretomba.

A questo dio inesorabile, che veniva rappresentato con in mano le chiavi, a indicare che chi entrava nel suo regno non avrebbe più fatto ritorno sulla Terra, non fu dedicato nessun tempio e i sacrifici che gli venivano offerti erano solo di animali neri (buoi o tori); il loro sangue, anziché essere raccolto sull'ara, veniva fatto scorrere nelle viscere della terra, perché giungesse nel regno infernale. Nelle sue rare apparizioni tra i vivi, il dio metteva in capo un elmo (kynéë) che lo rendeva invisibile. Ades (o Ade) significò anche il Regno dei Morti, come l'Erebo o gli Inferi. I Romani adorarono questo dio con il nome di Plutone.

Enciclopedia De Agostini

Ade

Ade (in latino Aides oppure Hades, -ae) è una divinità della mitologia greca, fratello di Zeus e di Poseidone. La sua sposa è tradizionalmente Persefone. Dati i suoi attributi mitici avrebbe come corrispettivi nella mitologia egizia il dio Serapide e in quella romana il dio Plutone. È conosciuto anche come Axiokersos, poiché coniuge di Persefone soprannominata infatti "axiokersa", e Zeus Katakthonios, ossia "signore degli Inferi". Con Ade si vuole anche intendere più genericamente il mondo degli Inferi.

Inizialmente solo il caso genitivo del nome della divinità era impiegato come abbreviazione per intendere la casa del dio dell'oltretomba; in seguito, per estensione, si cominciò a utilizzare il termine in tale significato anche al nominativo.

Nella mitologia latina inizialmente Plutone (l'alter ego latino di Ade) è definito Signore degli Inferi, e solo successivamente Signore dell'Ade. Altro termine utilizzato è Averno, nome del lago dal quale si può accedere agli inferi.

Ade era figlio di Crono e di Rea, mentre i suoi fratelli e sorelle erano Estia, Demetra, Era, Zeus e Poseidone. Secondo il mito venne divorato dal padre insieme ai suoi fratelli e sorelle, con la sola eccezione di Zeus, che - salvato dalla madre - li trasse in salvo con uno stragemma. Secondo la Suda, un testo tardo-bizantino del X-XI secolo, avrebbe avuto una figlia di nome Macaria, dea della buona morte.

Ade partecipò alla Titanomachia, nell'occasione in cui i Ciclopi gli fabbricarono la kynéë, un copricapo magico in pelle d'animale che gli permetteva di diventare invisibile: così poté introdursi segretamente nella dimora di Crono rubandogli le armi e mentre Poseidone minacciava il padre col tridente Zeus lo colpì con la folgore.

In seguito, ricevette la sovranità del mondo sotterraneo e degli Inferi, quando l'universo fu diviso con i suoi due fratelli Zeus e Poseidone, che ottennero rispettivamente il regno dell'Olimpo e del mare. Viene annoverato saltuariamente fra le divinità olimpiche, nonostante questo sia contrario alla tradizione. Ade è d'altra parte assai poco presente nella mitologia, essendo essenzialmente legato ai racconti mitologici legati agli eroi: Orfeo, Teseo ed Eracle sono tra i pochi mortali ad averlo incontrato. Inoltre la tradizione lo vuole riluttante ad abbandonare il mondo dell'aldilà: le uniche due eccezioni si ricordano per il rapimento di Persefone e per ricevere alcune cure dopo essere stato ferito da una freccia di Eracle.

La leggenda lo vuole padrone delle greggi solari, al pascolo nell'isola Erizia, la cosiddetta isola rossa, dove il Sole muore quotidianamente. Il pastore era chiamato Menete. Tuttavia in queste storie è chiamato Crono, o Gerione.

Gian

Lorenzo Bernini, Ratto di Proserpina - 1621-22

Roma - Galleria Borghese

Ade,

innamorato di Persefone, la rapì con l'accordo di Zeus mentre stava

raccogliendo dei fiori in compagnia delle ninfe, secondo il mito nelle attuali

pianure di Enna. Sua madre, disperata per la scomparsa della figlia, la cercò

per nove giorni arrivando fino alle regioni più remote. Il decimo giorno, con

l'aiuto di Ecate![]() ed

Elio

ed

Elio![]() , seppe che il rapitore era il dio degli Inferi.

Adirata, Demetra abbandonò l'Olimpo e scatenò una tremenda carestia in tutta

la terra, affinché questa non offrisse più i suoi frutti ai mortali e agli

dei. Zeus tentò allora di riconciliare Ade e Demetra, affinché si evitasse

la fine del genere umano: inviò il messaggero Ermes al fratello, ordinandogli

di restituire Persefone, a patto che ella non si fosse cibata del cibo dei

morti. Ade non si oppose all'ordine ma, poiché Persefone era effettivamente

digiuna dal rapimento, la invitò a mangiare prima di tornare dalla madre: le

offrì così un melograno in dono, frutto proveniente dagli Inferi. In

procinto di mettersi sulla via di Eleusi, uno dei giardinieri di Ade, Ascalafo,

la vide mangiare pochi grani del melograno: in questo modo si compì dunque il

tranello ordito da Ade, affinché Persefone restasse con lui negli Inferi.

Allo scatenarsi nuovamente dell'ira di Demetra, Zeus propose un nuovo accordo,

per cui, dato che Persefone non aveva mangiato un frutto intero, sarebbe

rimasta nell'oltretomba solamente per un numero di mesi equivalente al numero

di semi da lei mangiati, potendo così trascorrere con la madre il resto

dell'anno; avrebbe trascorso così sei mesi con il marito negli Inferi, e sei

mesi con la madre sulla terra. La proposta fu accettata da entrambi, e da quel

momento si associarono la primavera e l'estate ai mesi che Persefone

trascorreva in terra dando gioia alla madre, e l'autunno e l'inverno ai mesi

che passava negli Inferi, durante i quali la madre languiva.

, seppe che il rapitore era il dio degli Inferi.

Adirata, Demetra abbandonò l'Olimpo e scatenò una tremenda carestia in tutta

la terra, affinché questa non offrisse più i suoi frutti ai mortali e agli

dei. Zeus tentò allora di riconciliare Ade e Demetra, affinché si evitasse

la fine del genere umano: inviò il messaggero Ermes al fratello, ordinandogli

di restituire Persefone, a patto che ella non si fosse cibata del cibo dei

morti. Ade non si oppose all'ordine ma, poiché Persefone era effettivamente

digiuna dal rapimento, la invitò a mangiare prima di tornare dalla madre: le

offrì così un melograno in dono, frutto proveniente dagli Inferi. In

procinto di mettersi sulla via di Eleusi, uno dei giardinieri di Ade, Ascalafo,

la vide mangiare pochi grani del melograno: in questo modo si compì dunque il

tranello ordito da Ade, affinché Persefone restasse con lui negli Inferi.

Allo scatenarsi nuovamente dell'ira di Demetra, Zeus propose un nuovo accordo,

per cui, dato che Persefone non aveva mangiato un frutto intero, sarebbe

rimasta nell'oltretomba solamente per un numero di mesi equivalente al numero

di semi da lei mangiati, potendo così trascorrere con la madre il resto

dell'anno; avrebbe trascorso così sei mesi con il marito negli Inferi, e sei

mesi con la madre sulla terra. La proposta fu accettata da entrambi, e da quel

momento si associarono la primavera e l'estate ai mesi che Persefone

trascorreva in terra dando gioia alla madre, e l'autunno e l'inverno ai mesi

che passava negli Inferi, durante i quali la madre languiva.

Secondo Ovidio e Strabone, Ade tentò di approffittarsi della ninfa Menta (Mínthë). Persefone, gelosa del marito, si dispiacque dell'unione e si infuriò quando Menta proferì contro di lei minacce spaventose e sottilmente allusive alle proprie arti erotiche. Persefone, sdegnata, la fece a pezzi: Ade le consentì di trasformarsi in erba profumata, la menta, ma Demetra la condannò alla sterilità, impedendole di produrre frutti. Leuce, un'altra ninfa figlia di Oceano, fu rapita da Ade e trasformata da Persefone in pioppo bianco presso la fontana della Memoria.

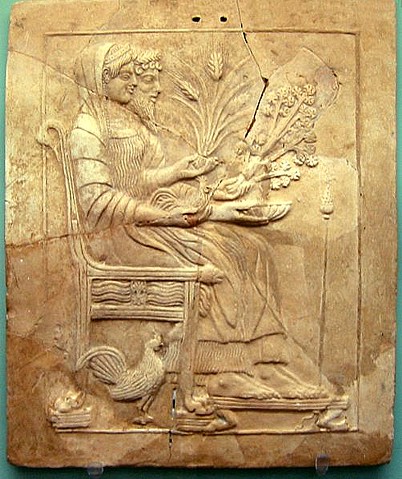

Pínax![]() con Persefone e Ade su trono, V secolo aC

con Persefone e Ade su trono, V secolo aC

da Locri Epizefiri, Italia (Reggio Calabria, Museo Nazionale della Magna

Grecia)

Per Ade si sacrificavano, unicamente nelle ore notturne, pecore o tori neri, e coloro che offrivano il sacrificio voltavano il viso: secondo Omero, infatti, Ade era il più ripugnante degli dei. Il suo culto non era molto sviluppato ed esistono poche statue con sue raffigurazioni.

Dei pochi luoghi di culto a lui dedicati, il solo degno di nota è Samotracia, mentre si suppone ne esistesse un secondo situato nell'Elide, a nord ovest del Peloponneso; è possibile che un altro centro del suo culto si trovasse ad Eleusi, strettamente connesso con i misteri locali. Euripide indica che Ade non riceveva libagioni rituali.

Veniva solitamente rappresentato come un uomo maturo, barbuto e feroce, spesso seduto su un trono e dotato di una patera e di uno scettro, con il cane a tre teste protettore degli Inferi, Cerbero. A volte si trovava anche un serpente ai suoi piedi. Indossa molto spesso un elmo, oppure un velo che gli copre il volto e gli occhi.

Si hanno sue rappresentazioni in moltissimi contesti ceramici, soprattutto nelle pínakes di Locri Epizefiri. Altri esempi si conoscono in alcuni affreschi della Tomba dell'Orco (altro nome del dio) a Tarquinia, mentre ad Orvieto se ne ha una raffigurazione all'interno della Tomba Golini I. Per la Grecia si ricordano un trono del Partenone attribuito a Fidia e una base colonnare da Efeso, più esattamente dal Tempio di Artemide. Nel mondo romano i sarcofagi, soprattutto in età tardo antica, usavano rappresentare il ratto di Proserpina e dunque una raffigurazione del dio infernale.

Ade è l'antagonista principale del film d'animazione della Walt Disney Hercules, e appare inoltre nella serie animata televisiva basata su Hercules e nella serie di videogiochi Kingdom Hearts. Come dio benevolo è fra i protagonisti di entrambe le serie televisive di Hercules e Xena: Principessa Guerriera. Inoltre è uno dei personaggi principali del manga I Cavalieri dello zodiaco, in cui i protagonisti sono coinvolti in un combattimento finale contro Hades, quale dio degli Inferi. Infine si trova anche come personaggio non giocante dei videogiochi per PlayStation 2 God of War e God of War II.

Hades refers both to the ancient Greek underworld, the abode of Hades, and to the god of the dead himself. Hades in Homer referred just to the god; Haidou, its genitive, was an elision of "the house of Hades." Eventually, the nominative, too, came to designate the abode of the dead.

In Greek mythology, Hades and his brothers Zeus and Poseidon defeated the Titans and claimed rulership over the universe ruling the underworld, sky, and sea, respectively. Because of his association with the underworld, Hades is often interpreted as a grim figure.

Hades was also called Plouto, and by this name known as "the unseen one", or "the rich one". In Roman mythology, Hades/Pluto was called Dis Pater and Orcus. The corresponding Etruscan god was Aita. The symbols associated with him are sceptre, cornucopia, and the three-headed dog, Cerberus.

In Christian theology, the term hades refers to the abode of the dead, where the dead await Judgement Day either at peace or in torment (see Hades in Christianity below).

Hades, Abode of the Dead

Hell - Underworld

In older Greek myths, Hades is the misty and gloomy abode of the dead, where all mortals go. There is no reward or special punishment in this Hades, akin to the Hebrew sheol. In later Greek philosophy appeared the idea that all mortals are judged after death and are either rewarded or cursed.

There

were several sections of Hades, including the Elysian Fields (contrast the

Christian Paradise or Heaven), and Tartarus, (compare the Christian Hell).

Greek mythographers were not perfectly consistent about the geography of the

afterlife. A contrasting myth of the afterlife concerns the Garden of the

Hesperides, often identified with the Isles of the Blessed, where the blest

heroes may dwell.

In Roman mythology, an entrance to the underworld located at Avernus, a crater

near Cumae, was the route Aeneas used to descend to the Underworld. By

synecdoche, "Avernus" could be substituted for the underworld as a

whole. The Inferi Dii were the Roman gods of the underworld.

The deceased entered the underworld by crossing the Acheron, ferried across by Charon, who charged an obolus, a small coin for passage, placed under the tongue of the deceased by pious relatives. Paupers and the friendless gathered forever on the near shore. Greeks offered propitiatory libations to prevent the deceased from returning to the upper world to "haunt" those who had not given them a proper burial. The far side of the river was guarded by Cerberus, the three-headed dog defeated by Heracles (Roman Hercules). Passing beyond Cerberus, the shades of the departed entered the land of the dead to be judged.

Since Hades was the ruler of the Underworld, it makes sense to note one of the key features of this region its myriad rivers. These rivers had names and symbolic meanings: the five rivers of Hades are Acheron (the river of sorrow), Cocytus (lamentation), Phlegethon (fire), Lethe (forgetfulness) and Styx (hate). See also Eridanos. The Styx forms the boundary between upper and lower worlds.

The first region of Hades comprises the Fields of Asphodel, described in Odyssey xi, where the shades of heroes wander despondently among lesser spirits, who twitter around them like bats. Only libations of blood offered to them in the world of the living can reawaken in them for a time the sensations of humanity.

Beyond lay Erebus, which could be taken for a euphonym of Hades, whose own name was dread. There were two pools, that of Lethe, where the common souls flocked to erase all memory, and the pool of Mnemosyne ("memory"), where the initiates of the Mysteries drank instead. In the forecourt of the palace of Hades and Persephone sit the three judges of the Underworld: Minos, Rhadamanthys and Aeacus. There at the trivium sacred to Hecate, where three roads meets, souls are judged, returned to the Fields of Asphodel if they are neither virtuous nor evil or sent by the road to Tartarus if they are impious or evil, or sent to Elysium (Islands of the Blest) with the heroic or blessed.

In the Sibylline Oracles, a curious hodgepodge of Greco-Roman and Judaeo-Christian elements, Hades again appears as the abode of the dead, and by way of folk etymology, it even derives Hades from the name Adam (the first man), saying it is because he was the first to enter there.

Hades in Christianity

Like other first-century Jews literate in Greek, early Christians used the Greek word Hades to translate the Hebrew word Sheol. Thus, in Acts 2:27, the Hebrew phrase in Psalm 16:10 appears in the form: "you will not abandon my soul to Hades." Death and Hades are repeatedly associated in the Book of Revelation. The word "Hades" appears in Jesus' promise to Peter: "And I also say unto thee, that thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it", and in the warning to Capernaum: "And thou, Capernaum, shalt thou be exalted unto heaven? thou shalt go down unto Hades." The word also appears in Luke's story of Lazarus and the rich man, which shows that Sheol/Hades, which had originally been seen as dark and gloomy, with little if any relation to afterlife rewards or punishments, had come to be understood as a place of comfort for the righteous ("in the bosom of Abraham") and of torment for the wicked ("in anguish in this flame").

The Greek word "Hades" was translated into Latin as infernus (underworld) and passed into English as "hell," as in the King James Version of the above-cited New Testament passages. The word continued to be used to refer generically to the abode or situation of the dead, whether just or unjust, as in the Apostles' Creed, where it is said of Christ, "he descended into hell". But, except in Greek, this generic usage of the word "Hades", "infernus", "hell" has become archaic and unusual. In Greek, the word kólasis (literally, "punishment"; cf. Mathew 25:14, which speaks of "everlasting kolasis") is used to refer to what nowadays is usually meant by "hell" in English.

Hades has often been pictured as a place within the earth, rather than just a state of the soul. Tertullian, speaking of those who did not believe in the Resurrection of the dead, wrote: "You must suppose Hades to be a subterranean region, and keep at arm's length those who are too proud to believe that the souls of the faithful deserve a place in the lower regions."

For souls in the situation of Hades, understood as that of the dead in general, early Christians believed that it is possible, not only for those who died before the coming of Christ, but also for those who died later "to be translated to a state of happiness" when prayed for, even if they were not baptized.

The ancient Christian Churches hold that a final universal judgement will be pronounced on all human beings when soul and body are reunited in the resurrection of the dead. They also believe that, even while awaiting resurrection, the fate of souls differs: "The souls of the righteous are in light and rest, with a foretaste of eternal happiness; but the souls of the wicked are in a state the reverse of this." Meanwhile, the saints among the dead can intercede for the living, and the living can help "such souls as have departed with faith, but without having had time to bring forth fruits worthy of repentance towards the attainment of a blessed resurrection by prayers offered in their behalf, especially such as are offered in union with the oblation of the bloodless sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ, and by works of mercy done in faith for their memory."

In Protestantism, it is believed that a person's fate is definitively sealed at death, and that the dead can neither assist the living nor be assisted by them.[citation needed] Some other sects, such as the Jehovah's Witnesses, hold that, until the resurrection, the dead simply cease to exist or, if they exist at all, do so in a state of unconsciousness.

Hades the lord of the Underworld

In Greek mythology, Hades (the "unseen"), the god of the underworld, was a son of the Titans, Cronus and Rhea. He had three younger sisters, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera, as well as two brothers , Poseidon his older brother and Zeus his younger brother: the six of them were Olympian gods.

Upon reaching adulthood Zeus managed to force his father to disgorge his siblings. After their release the six younger gods, along with allies they managed to gather, challenged the elder gods for power in the Titanomachy, a divine war. Zeus, Poseidon and Hades received weapons from the three Cyclopes to help in the war. Zeus the thunderbolt; Hades the Helm of Darkness; and Poseidon the trident. During the night before the first battle Hades put on his helmet and, being invisible, slipped over to the Titans' camp and destroyed their weapons. The war lasted for ten years and ended with the victory of the younger gods. Following their victory, according to a single famous passage in the Iliad (xv.18793), Hades and his two brothers, Poseidon and Zeus, drew lots for realms to rule. Zeus got the sky, Poseidon got the seas, and Hades received the underworld, the unseen realm to which the dead go upon leaving the world as well as any and all things beneath the earth.

Hades obtained his eventual consort and queen, Persephone, through trickery, a story that connected the ancient Eleusinian Mysteries with the Olympian pantheon. Helios told the grieving Demeter that Hades was not unworthy as a consort for Persephone:

"Aidoneus, the Ruler of Many, is no unfitting husband among the deathless gods for your child, being your own brother and born of the same stock: also, for honor, he has that third share which he received when division was made at the first, and is appointed lord of those among whom he dwells."

Despite modern connotations of death as "evil," Hades was actually more altruistically inclined in mythology. Hades was often portrayed as passive rather than evil; his role was often maintaining relative balance.

Hades ruled the dead, assisted by others over whom he had complete authority. He strictly forbade his subjects to leave his domain and would become quite enraged when anyone tried to leave, or if someone tried to steal the souls from his realm. His wrath was equally terrible for anyone who tried to cheat death or otherwise crossed him, as Sisyphus and Pirithous found out to their sorrow.

Besides Heracles, the only other living people who ventured to the Underworld were all heroes: Odysseus, Aeneas (accompanied by the Sibyl), Orpheus, Theseus, Pirithoüs, and Psyche. None of them was especially pleased with what they witnessed in the realm of the dead. In particular, the Greek war hero Achilles, whom Odysseus met in Hades (although some believe that Achilles dwells in the Isles of the Blest), said:

"Do

not speak soothingly to me of death, glorious Odysseus. I should choose to

serve as the hireling of another, rather than to be lord over the dead that

have perished."

Achilles' soul to Odysseus. Homer, Odyssey 11.488

Hades,

labelled as "Plouton", "The Rich One", bears a cornucopia

on an Attic red-figure amphora, ca 470 BC

Hades, god of the dead, was a fearsome figure to those still living; in no hurry to meet him, they were reticent to swear oaths in his name, and averted their faces when sacrificing to him. To many, simply to say the word "Hades" was frightening. So, euphemisms were pressed into use. Since precious minerals come from under the earth (i.e., the "underworld" ruled by Hades), he was considered to have control of these as well, and was referred to as Plouton (related to the word for "wealth"), hence the Roman name Pluto. Sophocles explained referring to Hades as "the rich one" with these words: "the gloomy Hades enriches himself with our sighs and our tears." In addition, he was called Clymenus ("notorious"), Eubuleus ("well-guessing"), and Polydegmon ("who receives many"), all of them euphemisms for a name it was unsafe to pronounce, which evolved into epithets.

Although he was an Olympian, he spent most of the time in his dark realm. Formidable in battle, he proved his ferocity in the famous Titanomachy, the battle of the Olympians versus the Titans, which established the rule of Zeus.

Because of his dark and morbid personality, he was not especially liked by either the gods nor the mortals. Feared and loathed, Hades embodied the inexorable finality of death: "Why do we loathe Hades more than any god, if not because he is so adamantine and unyielding?" The rhetorical question is Agamemnon's (Iliad ix). He was not, however, an evil god, for although he was stern, cruel, and unpitying, he was still just. Hades ruled the Underworld and therefore most often associated with death and was feared by men, but he was not Death itself the actual embodiment of Death was Thanatos.

When the Greeks propitiated Hades, they banged their hands on the ground to be sure he would hear them. Black animals, such as sheep, were sacrificed to him, and the very vehemence of the rejection of human sacrifice expressed in myth suggests an unspoken memory of some distant past. The blood from all chthonic sacrifices including those to propitiate Hades dripped into a pit or cleft in the ground. The person who offered the sacrifice had to avert his face. Every hundred years festivals were held in his honor, called the Secular Games.

Hades' weapon was a two-pronged fork, which he used to shatter anything that was in his way or not to his liking, much as Poseidon did with his trident. This ensign of his power was a staff with which he drove the shades of the dead into the lower world.

His identifying possessions included a famed helmet of darkness, given to him by the Cyclopes, which made anyone who wore it invisible. Hades was known to sometimes loan his helmet of invisibility to both gods and men (such as Perseus). His dark chariot, drawn by four coal-black horses, always made for a fearsome and impressive sight. His other ordinary attributes were the Narcissus and Cypress plants, the Key of Hades and Cerberus, the three-headed dog. He sat on an ebony throne.

In the Greek version of an obscure Judaeo-Christian work known as 3 Baruch (never considered canonical by any known group), Hades is said to be a dark, serpent-like monster or dragon who drinks a cubit of water from the sea every day, and is 200 plethra (20,200 English feet, or nearly four miles) in length.

Artistic representations

Hades is rarely represented in classical arts, save in depictions of the Rape of Persephone. Hades is also mentioned in The Odyssey, when Odysseus visits the underworld as part of his journey. However, in this instance it is Hades the place, not the god.

Persephone

and Hades Ploutos

tondo of an Attic red-figured kylix, ca. 440430 BCE

Persephone

The consort of Hades, and the archaic queen of the Underworld in her own right, before the Hellene Olympians were established, was Persephone, represented by the Greeks as daughter of Zeus and Demeter. Persephone did not submit to Hades willingly, but was abducted by him while picking flowers with her friends. Persephone's mother missed her and without her daughter by her side she cast a curse on the land and there was a great famine. Hades tricked Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds (though some stories say they fell in love and to ensure her return to him, he gave her the pomegranate seeds):

"But he on his part secretly gave her sweet pomegranate seed to eat, taking care for himself that she might not remain continually with grave, dark-robed Demeter."

Demeter questioned Persephone on her return to light and air:

" but if you have tasted food, you must go back again beneath the secret places of the earth, there to dwell a third part of the seasons every year: yet for the two parts you shall be with me and the other deathless gods."

Thus every year Hades fights his way back to the land of the living with Persephone in his chariot. Famine (autumn and winter) occurs during the months that Persephone is gone and Demeter grieves in her absence. It is believed that the last half of the word Persephone comes from a word meaning 'to show' and evokes an idea of light. Whether the first half derives from a word meaning 'to destroy' in which case Persephone would be 'she who destroys the light.'

Theseus and Pirithous

Hades imprisoned Theseus and Pirithous, who had pledged to marry daughters of Zeus. Theseus chose Helen and together they kidnapped her and decided to hold onto her until she was old enough to marry. Pirithous chose Persephone. They left Helen with Theseus' mother, Aethra and traveled to the underworld. Hades pretended to offer them hospitality and set a feast; as soon as the pair sat down, snakes coiled around their feet and held them there. Theseus was eventually rescued by Heracles but Pirithous remained trapped as punishment for daring to seek the wife of a god for his own.

Heracles

Heracles' final labour was to capture Cerberus. First, Heracles went to Eleusis to be initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries. He did this to absolve himself of guilt for killing the centaurs and to learn how to enter and exit the underworld alive. He found the entrance to the underworld at Tanaerum. Athena and Hermes helped him through and back from Hades. Heracles asked Hades for permission to take Cerberus. Hades agreed as long as Heracles didn't harm him, though in some versions, Heracles shot Hades with an arrow. When Heracles dragged the dog out of Hades, he passed through the cavern Acherusia.

Orpheus and Eurydice

Hades showed mercy only once: Because the music of Orpheus was so hauntingly good, he allowed Orpheus to bring his wife, Eurydice back to the land of the living as long as she walked behind him and he never tried to look at her until they got to the surface. Orpheus agreed but, he thought that Hades had played a trick on him, he thought that Hades might have given him the wrong soul or that there was another spirit named Eurydice. He glanced backwards, and failed, therefore losing Eurydice again, to be reunited with her only after his death.

Minthe and Leuce

According to Ovid, Hades pursued and would have won the nymph Minthe, associated with the river Cocytus, had not Persephone turned Minthe into the plant called mint. Similarly the nymph Leuce, who was also ravished by him, was metamorphosed by Hades into a white poplar tree after her death. Another version is that she was metamorphosed by Persephone into a white poplar tree while standing by the pool of Memory.

Epithets and other names

Hades, "the son of Cronos, He who has many names" was the "Host of Many" in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.The most feared of the Olympians had euphemistic names as well as attributive epithets.

Aides

Aïdoneus

Chthonian Zeus

Haides

Pluton

Plouto(n) ("the giver of wealth")

The Rich One

The Unseen One

The Silent One

Roman mythology

Dis

Dis Pater

Dis Orcus

Giglio Gregorio Giraldi![]()

Historiae Deorum Gentilium (1548) Syntagma VI

[p.266] Hades vero, hoc est Ἅδης. plerique, ut Socrates ait apud Platonem, mihi videntur interpretari, quasi ἀειδὲς, id est triste, vel tenebrosum. Et proinde timentes hoc nomen, Plutonem vocarunt, quam tamen sententiam idem mox impugnat: siquidem, ait, plurimi quotidie illum subterfugerent, nisi fortissimo vinculo eos qui illuc descendunt, ligaret. tum subinfert, cupiditate validissima eos Haden illigare, qui illuc descendunt, quod nullus revertatur. Et propterea illum tanquam doctissimum sophistam Evergeten, id est beneficium esse dicit, [p.267] qui ingentia, his qui penes ipsum habitant, conferat beneficia: utpote qui usqueadeo divitiis abundet, ut inde Pluto sit nuncupatus. Atque ita etiam paulo post subdit: Ἅδης igitur minime, quasi ἀειδὲς, id est triste vel tenebrosum, sed potius .ἀπο του πάντα τὰ καλὰ εἰδέναι, quod noscat omnia pulchra. At vero Phurnutus ait Haden appellari, quod uideri minime possit, quasi ἀόρατον. Hinc et per diaeresin Ἄϊδα vocarunt. vel per contrarium, ceu ἀνδάνων ἡμῖν τοῦ θανάτου, hoc est, morte nobis placens. Alii ab ἀ et ἐινδεῖν, id est, non videndo derivant, quod et Gaza notat, licet denso spiritu proferatur. unde et Vergilius dicit, Sine sole domos. hinc et .Ἀΐδης dictus est.

Aidoneus etiam Pluto cognominatus est, ab αἴδης, quae vox scripta per propriam diphthongum, sine afflatu apud Graecos legitur, per impropriam vero diphthongum, hoc est ἅδης afflatur. Sic et Aidoneus, de quo sic Philochorus in Atthidis libro secundo, et Eusebius in Chronicis: Fabula Proserpinae, quam rapuit Aidoneus, id est Orcus, rex Molossorum, cuius canis ingentis magnitudinis, Cerberus nomine, Perithoum devoravit, qui ad raptum uxoris cum Theseo uenerat: quem et ipsum iam in mortis periculo constitutum, adueniens Hercules liberauit. et ob id quasi ab inferis receptus dicitur. Eandem fabulam Plutarchus in Theseo recitat: sed Cererem Aidonei uxorem, et Proserpinam filiam dicit. caetera pene eodem modo. Sane et Plutoni pallacem, id est concubinam Minthen, ascribit in primis Iulius Pollux in sexto, et ante Pollucem Strabo in octavo, sed et utroque antiquior Nicander poeta in Alexipharmacis, καὶ χλοεραὶ ἀπό µίνθες φυλλάδες, ἠὲ µελίσσης, id est, Viridia minthae folia, sive melissae: quo loco et Scholiastes fabulam recitat. Quin et poeta noster Ovidius in Metamorphosi eam in plantam mutatam innuit, cum ita in decimo canit:

An tibi

quondam

Foemineos artus in olentes uertere minthas

Persephone licuit.

Vide et Oppinianum post Ovidium, libro tertio Halieuticon, qui copiosius hanc fabulam est executus. plura Coelius, et Ruellius de mentha.

Agesilaus Pluto cognominatus, παρὰ τὸ ἄγειν τοὺς λαοὺς, quod scilicet populos agat. est enim inferorum et mortuorum deus existimatus a gentibus. huius meminit in primo Lactantius Firmianus: et Callimachus, qui ait, φοιτῶσι µεγάλῳ Ἀγεσίλεῳ, hoc est, Ad magnum pergunt Agesilaum. De Agesilao Plutone, ex Methodio et Aeschylo plura Athenaeus. Sunt tamen qui apud Lactantium, pro Agesilao Agelastum legant, quod sine risu deus sit, sed luctuosus. [p.268] Legimus quippe Agelastum Plutonem vocari: et Agathalyum, quod mortalium bona solvat.

Λάγετας quoque Pluto cognominatus est Pindaro, quod (ut exponunt eius interpretes) πάντας λάγει λαοὺς, id est, omnes agat populos.

Axiocerses Pluto cognominatus est in Cabirorum et Samothracum sacris, sicut legimus in Commentariis in Apollonium Rhodium, et a me alibi pluribus relatum est.

Ἀρειµανὴς vero .Ἀΐδης apud Persas, teste Hesychio, dictus. Arimanes quidem, et Plutarchus, aliique meminere, sed non Plutonem expresse dixerunt.

Eubulus, et Eubulius, καὶ Εὐβουλεὺς Pluto cognominatus, quod mortalibus consulere crederetur, finemque curis ac laboribus caeterisque morbis afferre, ut in Alexipharmacis Nicandri interpretes exponunt. Praeter Nicandrum, et Orpheus in hymnis hoc cognomine est usus, et Phurnutus interpretatur. alium tamen Eubulium videtur Cicero facere in Natura deorum.

Clymenon etiam Plutonem cognominari, sunt qui scribant: quia sit causa τοῦ κλύειν. ictus enim aer, vox est. Aer autem qui animas excipit, Ἅδης, διὰ τὸ ἀειδὲς, ex obscuritatis ratione ab aliquibus dictus, ut superius ex Platone dictum. Idem scribit et Phurnutus. Lasus Hermionensis poeta in principio hymni quem in Cererem composuit, Δήμητραν μέλπω, κόραν τε κλυοµένοιο ἅλοχον, hoc est, Cererem cano Proserpinamque Plutonis coniugem. Legi etiam alicubi Κλύμιος Ἅδης, quod an recte scriptum, haud definio.

Leptynis Pluto, si non potius Proserpina: dicta est, quod mors ac interitus corpora mortalium attenuet. Chthonius Iupiter Pluto vocatus ab Orpheo, in hymno Eumenidum. eas enim magni Iovi Chthonii filias, et Proserpinae, cecinit. Vocatur idem a Trismegisto Hermete in Asclepio, Plutonius Iupiter.

Ισοδέτης, Isodetes (inquit Hesychius, et Phavorinus [Favorinus]) ab aliquibus Pluto. alii putant nomen daemonis ut in Daemonibus dicetur. Ab aliis Plutonis filius vocatus est. Πυλάρτην etiam cognominatum ab Homero ait Phurnutus, quod portas habeat, quas nullus non ingrediatur. Iam nunc ad eius latina nomina transeamus.

Orcus frequenter pro Plutone ipso, et inferis capitur, ab urgendo: tametsi quidam ex nostris Graecum potius putavere, ab iuramento deductum, et cum afflatu scribunt Horcum. alii, aspirationem additam in posteriore syllaba volunt, unde sit deductum nomen proprium Orchius, et lex Orchia apud Macrobium. Nos Festum potius audiamus, ita scribentem: Orcum quem dicimus, [p.269] ait Verrius, ab antiquis Uragum, quod etiam u literae sonum pro o efferebant, et pro C, G literae formam usurpabant. Sed nihil affert exemplorum, ut ita esse credamus, nisi quod is deus nos maxime urgeat. tantum ait Festus. Catullus:

At nobis male sit, malae tenebrae,

Orci, quae omnia bella devoratis.

Vergilius,

Vestibulum ante ipsum, primisque in faucibus: Orci. Ab Orco, Orcinius libertus

ab Iureconsultis dictus, is qui sit ipsius testatoris defuncti, et in Orci

familiam ascripti. Ulpianus: Qui directam, inquit, libertatem

acceperunt, Orcinii erunt liberti. Non me fugit aliter alios, et quidem eruditos,

sentire. Legimus et apud Martialem, illo scazonte, Orciniana qui feruntur in

sponda: dici pro feretro, et sandapila. de Orci vero galea iam actum est.

Summanus Pluto vocatus, quasi summus manium, cui (ut Plinius scribit) attribuebantur nocturna fulmina. In templis Iovis optimi maximi fastigio Summanus fuit, ut M. Cicero in libro de Divinatione scribit. Nonne, inquit, cum multa alia mirabilia, tum illud in primis, cum Summanus in fastigio Iovis optimi maximi qui tum erat fictilis, coelo ictus esset, nec usquam eius simulachri caput inveniretur, haruspices in Tiberim id depulsum esse dixerunt: idque inuentum est eo loco, qui est ab haruspicibus demonstratus. De Summano et in quarto D. Augustinus, Sic enim, inquit, apud ipsos Romanos legitur. Romani veteres nescio quem Summanum, cui nocturna fulmina tribuebant, coluerunt magis quam Iouem, ad quem diurna fulmina pertinebant. Sed postquam Iovi templum insigne ac sublime constructum est, propter aedis dignitatem sic ad eum multitudo confluxit, ut vix inveniatur, qui Summani nomen, quod audire iam non potest, se saltem legisse meminerit: Et reliqua. Quod ignobilis iam factus esset, innuit et Ovidius sexto Fastorum,

Reddita, quisquis is est, Summano templa feruntur,

Tunc, cum Romanis Pyrrhe timendus eras.

Varro de Lingua latina ait: Tito Tatio inter caeteros deos Summanum repositum. Summani et Martianus meminit, et Festus. Sed et Plautus in Bacchidibus ita inquit: Me Iupiter, Iuno, Ceres, Minerva, Latona, Spes, Ops, Virtus, Venus, Castor, Polluces, Mars, Mercurius, Hercules, Summanus, Sol, Saturnus, deique omnes ament. Fuit prope Circum maximum Summani aedes, ait Plinius, prope fanum Iuventatis, sacellum vero in Capitolio. Summanes demum apud Martianum deos legimus, qui alii sunt quam qui Semones dicebantur, de quibus suo loco disseruimus. [p.270]

Soranus Pluto a Sabinis nuncupatus, ex quo et Hirpini Sorani dicti, quasi Plutonii lupi: vel quod is deus ibi coleretur, vel quod rapto ex responso viverent. Quo de nomine talem legimus fabulam in undecimo Aeneidos, super illo, Summe deum sancti custos Soractis Apollo. Soractes, inquit Servius, mons est Hirpinorum, in via Flaminia collocatus. In hoc autem monte cum aliquando Diti patri sacrum persolveretur (nam Manibus consecratus est) subito venientes lupi exta rapuerunt: quos cum diu sequerentur, delati sunt ad quandam speluncam, halitum ex se pestiferum emittentem, adeo ut iuxta stantes necaret. et inde orta pestilentia est, quia fuerant lupos secuti. de qua responsum fuit, posse sedari, si lupos imitarentur: hoc est, si rapto viverent. quod posteaquam factum est, dicti sunt populi Hirpini Sorani. nam lupi Sabinorum lingua hirpi vocati. Sorani vero, a Dite. nam Ditis pater eadem lingua Soranus dicitur.

Postulio etiam Pluto vocatus, ut Varro docet de Lingua latina de Curtio lacu loquens: A Porcilio, inquit, delatum in eo loco dehisse terram, et id ex S.C. haruspicis relatum esse responsum, deum manium Postulionem postulare. Non desunt qui redarguant, si dis placet, hoc loco Varronem, vel magis mendosum codicem putent, Postulationemque legant, qua voce significari tradunt sacrum ad prodigium, vel deum iram avertendam, et amoliendam, ut quadam oratione innuit M. Cicero. Sed et Graecis, ut Phurnutus scribit, Pluto Πολυδέκτην, καὶ Πολυδέγµων, καὶ Πολύαρχος cognominatus est, quod multis dominetur.

Februus deus Pluto appellatus ab antiquis, a purgationibus et lustrationibus funerum. Multa Ovidius in Fastis, et nos plura in libro de Annis et mensibus.

Quietalis etiam Pluto dictus est, quia omnibus pausam afferat. Quietalis, inquit Festus, dicebatur ab antiquis Orcus. Vocatus insuper et Stygius Iupiter. Ovidius,

Saepe tibi

est Stygii regia visa Iovis.

Vergilius Sacra Ioui Stygio.

Eadem ratione et saepe Infernus Iupiter.

Claudianus:

Inferni raptoris equos.

Dictus idem Niger Iupiter. Silius libro octavo:

Nigro forte Ioui, cui tertia regna laborant.

Vedius praeterea, et Veiovis etiam appellatus, ut alio loco notavimus. Dux erebi etiam dictus est a poetis, et Rector profundi, et Elysii, et huiusmodi aliis plerique, ut ab aliis colligitur, qui hac parte studiosis literarum consuluerunt. Beelzebub ab Hebraeis et Chaldaeis Pluto dicitur, eadem pene qua Latini ratione Iovem Stygium, et Infernum Iouem appellant: [p.271] quippe Beel, ut diximus, Belus, fuit illis, qui Iupiter est. quidam Bahalzebub muscarum deum interpretantur. Sed ipse de hoc deo plura iam tibi collegi. Mammona alii appellant, ut nos Ditem, et graeci a divitiis Plutonem.

Serapin iure cum Plutonis nominibus coniungimus. nam idem cum Plutone existimatus est, ut Plutarchus in libro de Isi et Osiride docet, et Archematus Euboeus, qui non alium Serapin quam Plutonem, nec aliam Isin quam Proserpinam esse scribit. Quin et Ponticus Heraclides oraculum, quod celebre Serapidis fuit, Plutonis fuisse asserit. quod consulenti cuidam Aegypti regi, quisnam se esset beatior, ita respondisse fertur:

Principio Deus est, tum verbum, his spiritus una est,

Congenita haec tria sunt, cuncta haec tendentia in unum. Hoc est graece:

πρῶτα

θεὸς. µετέπειτα λόγος, καὶ

πνεῦµα σὺν

αὐτοῖς,

σύµφυτα δὴ τρία

πάντα

καὶ εἰς ἕν ἴοντα.