Lessico

Pulci

Siphonaptera o Aphaniptera

Sifonatteri o Afanitteri

Pulce in latino è pulex-icis, in greco psýlla o psýllos. Nome comune di tutti gli insetti dell'ordine Sifonatteri. La specie più nota è la pulce dell'uomo (Pulex irritans) della famiglia Pulicidi, detta anche pulce comune, parassita dell'uomo, ma che può vivere anche su molti altri mammiferi. È vettrice della peste bubbonica, del tifo murino e di vari stafilococchi.

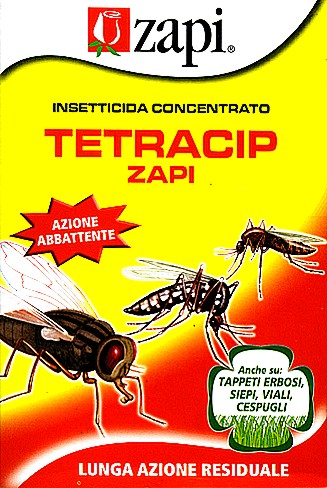

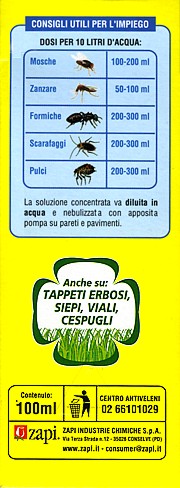

La pulce delle galline, Echidnophaga gallinacea, è diffusa nelle zone tropicali; vive su uccelli sia domestici (polli e tacchini) sia selvatici. Ma forse più importante è il Ceratophyllus gallinae, essendo la pulce più comune del pollame. Non ho trovato nel web un antipulce da usare per i polli. Grazie alla consulenza e alla collaborazione del negozio Dino Gatti di Valenza (AL) pare che il prodotto migliore attualmente disponibile sia il Tetracip (25 aprile 2008).

Regno: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: Hexapoda

Classe: Insecta

Sottoclasse: Pterygota

Coorte: Endopterygota

Superordine: Oligoneoptera

Sezione: Panorpoidea

Ordine: Siphonaptera

I Sifonatteri, Siphonaptera (da sifone, con allusione al succhiatoio + il greco ápteros, privo di ali), noti anche col nome comune di pulci, sono un ordine di insetti privi di ali. Sono detti anche Afanitteri (Aphaniptera, cioè, che non mostrano ali).

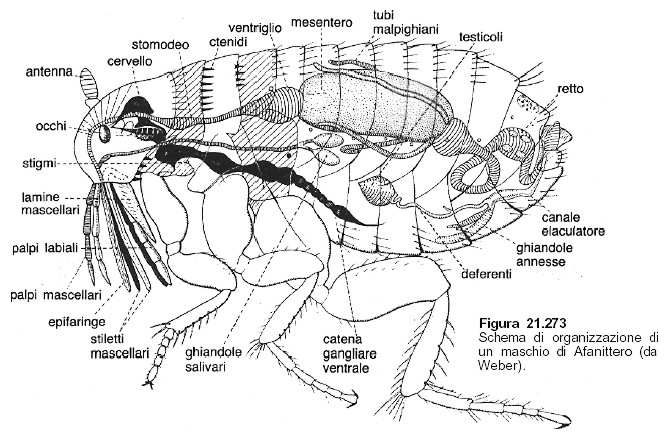

Gli Afanitteri sono Insetti atteri, olometaboli, con apparato boccale pungitore e succhiatore notevole per lo sviluppo dei palpi mascellari e labiali rispetto alle altre parti della mascella e del labio. Le loro affinità restano tuttora assai dubbie. Hanno larve apode. L'ordine comprende un migliaio di specie ectoparassite di Vertebrati a sangue caldo, ematofaghe, che passano facilmente da un ospite all'altro, abbandonandolo in ogni caso non appena questo, eventualmente venuto a morte, comincia a raffreddarsi.

Parecchie specie sono parassite di una sola specie, altre invece possono infestare più specie di Mammiferi o di Uccelli. In generale misurano qualche millimetro di lunghezza, ma taluna specie raggiunge i 7 mm. Se ne conosce qualche fossile del Terziario.

A differenza dagli altri Insetti parassiti atteri il corpo degli Afanitteri (fig. 21.271) è fortemente compresso lateralmente. In quanto alle ali, non se n'è potuto riscontrare alcuna sicura traccia in nessuno stadio della loro vita. I tegumenti sono fortemente sclerificati, con serie di spine e di setole che, essendo rivolte posteriormente, facilitano la locomozione fra i peli o le penne dell'ospite.

Struttura

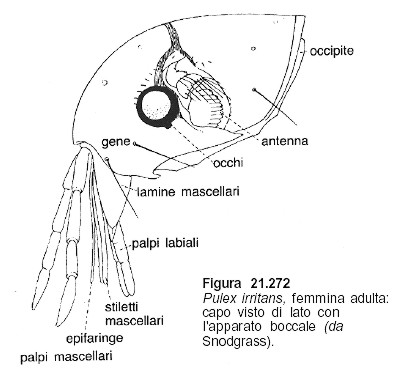

Il capo è spesso diviso in due o tre sezioni mobili l'una rispetto all'altra, ma è poco mobile rispetto al torace. Gli occhi, talora vestigiali o assenti, talora depigmentati, sono semplici (non faccettati) e situati davanti a un paio di brevissime antenne le quali rimangono adagiate in apposite fossette e si presentano ingrossate, triarticolate, con l'articolo terminale percorso da solchi anulari.

I margini latero-ventrali del capo sono frequentemente orlati da una serie di robuste spine, costituendo i cosiddetti pettini genali o ctenidi, bene sviluppati in Ctenocephalides. L'apparato boccale è pungitore e succhiatore (fig. 21.272). Le mandibole, allungatissime laminari-stiliformi sono piegate a doccia in modo da combaciare con i margini posteriori e da abbracciare con i margini superiori il labbro superiore ugualmente allungato e stiliforme, formando con questo un canale che nello stesso tempo serve per succhiare il sangue delle vittime e per immettere nella ferita saliva iperemizzante, la quale sgorga all'estremità di una brevissima prefaringe situata tra il labbro e le mandibole alla base del rostro.

Le mascelle bene sviluppate consistono in un paio di lamine triangolari e in un paio di palpi 4-articolati che partono da un pezzo basale (cardine e stipite coalescenti). Il labbro inferiore consta di un breve pezzo basale (mento e submento coalescenti), è privo di lobi, ma porta all'estremità distale un paio di palpi 1-5 articolati (talora suddivisi fino a 17 articoli) che, piegati a doccia, formano le due metà laterali di una sorta di guaina che protegge le mandibole e il labbro superiore.

I segmenti toracici sono mobili; il margine posteriore tergale del primo di essi è spesso orlato di spine formanti un pettine pronotale. Gli epimeri del meso- e del metatorace sono così sviluppati da ricoprire la base dell'addome.

Le zampe presentano grandi coxe piatte, femori relativamente brevi ma robusti e lungo tarso 5-articolato e terminato da un paio di unghie; quelle dell'ultimo paio sono notevolmente più lunghe e robuste delle precedenti e atte al salto.

L'addome consta (almeno apparentemente) di 10 segmenti, di cui i 3 ultimi e specialmente il 9° subiscono modificazioni sessuali. L'8° segmento è assai corto e di solito affondato e nascosto nel 7°. Il 9° segmento nel maschio presenta una placca dorsale (detta placca pigidiale) con particolari setole sensorie, mentre lateralmente un paio di scleriti tergali formano il forcipe per l'accoppiamento. Il 10° segmento è rappresentato da due placchette, una dorsale e una ventrale, fra le quali sbocca l'ano, partecipando alla formazione del pene che ha forma allungata e rimane protetto dal forcipe e da 2 placche sternali del 9° segmento. Nella femmina esiste la placca sensoria pigidiale; ventralmente tra il 9° e il 10° sternite si apre la vagina, e la placchetta dorsale del 10° segmento reca un processo conico detto stilo.

Il canale alimentare (fig. 21.273) si inizia alla base del palato con una faringe muscolosa atta ad aspirare il sangue dell'ospite. Al sottile esofago privo di ingluvie fa seguito un ventriglio le cui pareti interne sono armate di file di placchette cuticolari costituendo un apparato valvolare atto a impedire il rigurgito del sangue già introdotto nell'intestino medio, il quale è ampio e assai dilatabile. Fra l'intestino medio e il posteriore sboccano 4 tubi malpighiani; il retto è provvisto di 6 papille rettali simili a quelle dei Ditteri. Un paio di ghiandole salivari ovoidi uniscono i loro condotti prima di gettarsi dietro l'ipofaringe.

Il sistema respiratorio è bene sviluppato con 2 paia di stigmi toracici e 8 addominali. Il sistema nervoso, assai primitivo, mostra 3 gangli toracici e 7-8 addominali molto ravvicinati.

Riproduzione e sviluppo

L'apparato genitale maschile consta di un paio di testicoli fusiformi e di un paio di sottili deferenti che si riuniscono, e dopo aver comunicato con una piccola vescicola seminale e due paia di ghiandole accessorie immette nel canale eiaculatore associato all'edeago. Gli spermatozoi, ad acrosoma assai ridotto o assente, hanno assonema «9+2» come quello dei Mecotteri.

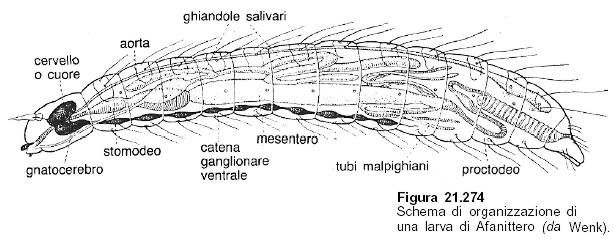

Gli ovari» constano ciascuno di 4-8 ovarioli panoistici allineati lungo i brevi ovidotti che conducono alla vagina, a cui sono annessi una borsa copulatrice dorsale e uno o due ricettacoli seminali situati all'apice di due condotti ghiandolari (o di uno di essi). Le uova, dal corion sottile, prive di sostanze adesive annesse, anche se depositate sull'ospite, finiscono per cadere sul substrato (nidi, tane, terreno). Dopo 3-10 giorni ne sguscia una larva bianca, vermiforme, apoda, prognata, con una spina frontale che è servita per rompere il corion dell'uovo e che viene perduta alla prima muta.

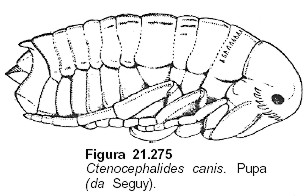

Le larve (fig. 21.274) si nutrono di detriti organici e di feci di Pulci adulte, accrescendosi rapidamente. Dopo aver subito due mute si ricoprono di polvere e di detriti vari, tessono un piccolo bozzolo con la seta prodotta dalle ghiandole labiali, si ripiegano su se stesse e subiscono un'ultima muta larvale trasformandosi in pupe exarate (fig. 21.275) che gradatamente divengono di color bruno.

Gli adulti possono restare a lungo entro il bozzolo pupale; perché ne fuoriescano è necessaria un'eccitazione meccanica quale il passaggio di un ospite, il contatto con questo, le vibrazioni che esso produce, ecc. Così si spiega la contemporanea improvvisa comparsa di gran numero di adulti. Lo sviluppo, a ogni modo, si compie in 20-80 giorni a seconda delle specie e della temperatura.

Ecologia

Tutti gli Afanitteri adulti possono trasmettere gli agenti di varie malattie: l'infezione avviene attraverso le lesioni della pelle ed è operata mediante l'eventuale rigurgito o più spesso mediante le feci abitualmente emesse nel momento in cui viene succhiato il sangue dell'ospite.

Particolarmente pericolose sono le Pulci nei casi di peste bubbonica che nei paesi tropicali viene abitualmente trasmessa dai Topi all'Uomo per opera di Xenopsylla cheopis, ospite consueto di ambedue le specie, mentre le Pulci dei Topi dei nostri paesi temperati solo eccezionalmente attaccano l'Uomo.

Ad ogni modo non meno di 9 specie sono in grado di trasmettere la peste all'Uomo; fra le altre specie animali soggette a tale infezione, oltre i Topi, bisogna tener presente vari altri Roditori.

Sistematica

Appartengono agli Afanitteri le famiglie degli Ectopsillidi (o Dermatofilidi), Iscnopsillidi e Pulicidi.

Negli Ectopsillidi la femmina contrae intimi rapporti con l'ospite: così Tunga penetrans dell'America meridionale, dell'Africa occidentale e del Madagascar, la cui femmina si addentra nella pelle umana, specialmente dei piedi, dove il suo addome carico di uova si rigonfia straordinariamente divenendo sferico. Le uova vengono depositate nella stessa cavità abitata dalla madre.

Tanto gli Iscnopsillidi che i Pulicidi vivono liberi sui loro ospiti: fra i primi ricordiamo gli Ischynopsyllus parassiti dei Pipistrelli; ai Pulicidi, mai trovati sui Pipistrelli e caratterizzati dalle mascelle triangolari con apice acuto, appartengono la comune Pulex irritans, maschio 2 mm, femmina 3-4 mm, le Pulci dei Cani e dei Gatti Ctenocephalides canis e C. felis, maschio 2 mm, femmina 3 mm e la temibile Pulce dei Topi (Xenopsylla cheopis, 2-3 mm), Ceratophyllus gallinae, 3 mm, che attacca i Polli ed altri Uccelli,TrichopsyIla penicilliger comune su numerosi Uccelli e Mammiferi (Topi compresi), Nosopsyllus fasciatus, 1-2 mm, ospite dei Topi nelle regioni fredde.

Fleas are blood sucking insects belonging to the order Siphonaptera. Fleas are thought to be closely related to Diptera (True Flies). Although ectoparasites the wings of fleas have been lost during their evolution but it has been suggested that muscles that may have been used for flight are now used to power the well developed rear legs. The rear legs arise from the metathorax and this area is well developed as a consequence of this.

In contrast to Anoplura, fleas are flattened laterally allowing them to travel quickly through host hair. Morphological adaptations other than lateral flattening include recessed antennae-long antennae would only serve to obstruct a fleas passage- and backward pointing setae, these anchor the flea against surrounding hairs if attempts are made to remove them. Many species of flea have a particular arrangement of setae on the thorax which are called combs.

Fleas lack compound eyes but do posses ocelli on either side of the head, although some species do lack even these, eg Leptopsylla segnis - the house mouse flea. Sexes can be distinguished by the presence of complex copulatory apparatus on males. These apparatus are situated to the rear and ventrally and in addition to males having a pronounced curvature of the ventral surface opposed to a flat surface in females these features serve to sex fleas.

Fleas are important from a medical view point because they transmit harmful pathogens from animals to humans. These pathogens cause plague and murine typhus although as these are of medical importance rather than veterinary they will not be discussed here. In the case of Spilopsyllus cuniculi, the rabbit flea transmission of Fibromavirus myxomatosis has been a advantage in attempts to control rabbit populations.

Combined with the production losses caused by pathogen transmission is that seen in the sticktight flea which, if present in large enough numbers can cause anaemia and emaciation in poultry. This is often combined with reduced egg production and if infestation is particularly heavy then death of birds will result, especially those that are young or old. The sticktight flea is not a active jumping flea rather a burrow in and stay flea. Fleas have a less specific range of hosts than Anoplura and Mallophaga which increases the chance of pathogen transmission.

Fleas can be divided into three superfamilies, the Pulicoidea, Ceratophylloidea and the Malacopsylloidea. Most fleas of medical and veterinary importance belong to the superfamily Pulicoidea, including the human flea Pulex irritans which normally parasitizes pigs. Fleas of veterinary importance are Echidnophaga gallinacea known as the sticktight poultry flea (mentioned above), and Ceratophyllus gallinae also a poultry flea, this flea parasitizes many other bird species as well as poultry.

The life cycle of fleas differs from that seen in both lice orders. Fleas are pterygotes and are placed in the Holometabola (insects that undergo metamorphosis during their life cycle) group. Typical life cycle is egg-larva-pupa-adult. A flea does not attach its eggs to the host and the larvae develop away from the host, usually within the hosts nest or burrow. Eggs are quite large in comparison to the female, being approximately 0.5 mm. A female flea will produce and lay between two and six eggs a day. These are oval and off-white in colour. The total egg production of female fleas differs with species and conditions the number usually quoted for Pulex irritans is around 400 eggs in a life time.

Eggs are laid either on the host and will then fall off or they are laid directly in the bedding material. If there is a relative humidity above 70% then eggs of most species hatch within three to six days. Eggs are susceptible to desiccation and if relative humidity falls below 70% egg mortality will become greatly increased.

From the egg a maggot type mobile larvae hatches. The larvae will burrow into the nesting material to feed on organic material and to avoid predator insects in the burrow. In a domestic setting such as a house or heated out-building fleas can quickly increase in population size and become extremely annoying and possibly destructive to weak poultry. The larva are vermiform (worm like) and measure between 3-10 mm in length when fully developed. Most species have three instar stages and larvae feed on organic matter such as sloughed skin from the host. Another food source of larvae is dried blood, this is provided by adult fleas that feed on a host and then excrete undigested blood.

This behaviour could be classed as altruistic as there is no way for adult fleas to ensure that their offspring only will receive these blood meals. At the third larval stage a thin silken cocoon is weaved. Emergence from cocoons is closely correlated to relative humidity and desiccation is the main cause of mortality at this stage in the life cycle.

Ambient temperature also effects emergence from cocoons with almost none occurring below 100 °C. Another adaptation of a fleas life cycle is that pupae will often not hatch unless an environmental stimulus is present. Research has shown that in Ctenocephalides felis the cat flea, pupa hatch very rapidly in response to vibration. This mechanism allows the pupa to remain dormant until a potential host approaches. Young adult fleas will then emerge extremely quickly from their silken pupal cases and jump immediately onto the nearby host.

Young adult fleas within their silken cocoons need to be able to escape the confines of their development compartment. To enable this a structure on the head called the frontal tubercle projects outwards and allows the fibers of the cocoon to be teased apart. The time spent in a cocoon can vary from one week to around twelve months and it is this factor that plays an enormous part in maintaining flea populations over periods when environmental conditions are unfavorable. Adult fleas when living in ideal conditions are able to live for a year or more.

Fleas of veterinary importance

The two most common fleas of veterinary importance are Ceratophyllus gallinae and Echidnophaga gallinacea. Both these fleas are parasites of domestic poultry. C. gallinae is the most common of the two and if excessive numbers are allowed to occur anaemia can result. C. gallinae will also bite humans and household pets and therefore can become household pests if not properly eradicated.

Female E. gallinacea - the stick-tight flea - usually burrows into the comb or wattles on poultry following fertilisation. A nodule results from this activity and within this nodule the eggs are laid. Once hatched the vermiform larvae exit the nodule and drop onto the substrate where they feed on organic debris. The burrowing into and subsequent emergence of larvae cause pathology to the skin tissue and can result in areas of ulceration. This can easily lead to secondary bacterial infection and with heavy flea burdens death can result. The stick-tight flea can occur at densities of over one hundred individuals per bird all concentrated around the head. Although difficult to determine it is probably best to assume that any infection is detrimental to egg laying or weight gain and so immediate action on discovery of this insect is the best policy. It is also worth noting that Echidnophaga will attack other mammals, mostly dogs, causing nodules around the eyes and between the pads on the paws.

Treatment and control

The treatment for the two species differs due to their differing ecology. Treatment for Ceratophyllus is performed using an insecticide such as malathion or carbaryl, malathion tends to be cheaper. These are used as dust formulations and both poultry and the poultry shed should be treated.

For Echidnophaga a solution formulation is needed as the wattle and comb need to be submerged for the insecticide to be effective. In addition to this treatment all bedding material and litter should be removed. Litter material should be burnt, food trays and any utensils or objects that could harbour larvae should be thoroughly cleaned before being returned. The poultry house should be rigorously sprayed with an insecticide such as a 1% solution of ronnel applied according to the manufacturers guidelines. Regular inspection of birds for flea infestation should be carried out and prompt treatment should be performed if present.

www.roberth.u-net.com

Ceratophyllus gallinae è la pulce più comune del pollame Può causare irritazioni, intenso disturbo e anemia. Può facilmente essere reperita sull’uomo e sugli animali d’affezione. Possono anche entrare nelle abitazioni spostandosi da zone di nidificazione attigue.

Ceratophyllus

gallinae

The common hen flea

Ceratophyllus gallinae is a species of flea that feeds on many different birds, as well as a few mammals. In Europe, however, the vast majority of its hosts are hole-nesting tits, particularly great tits and blue tits. I worked with C. gallinae at the University of Bern, Switzerland, from 1994 to 1997, looking for effects of variation in host quality and nutritional status on flea fitness.

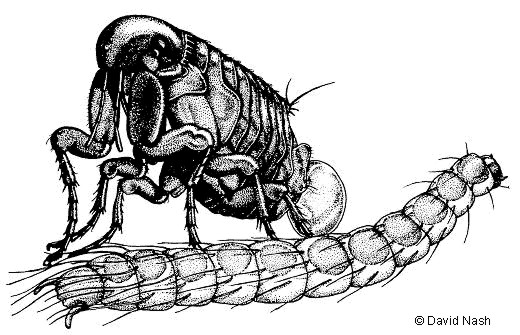

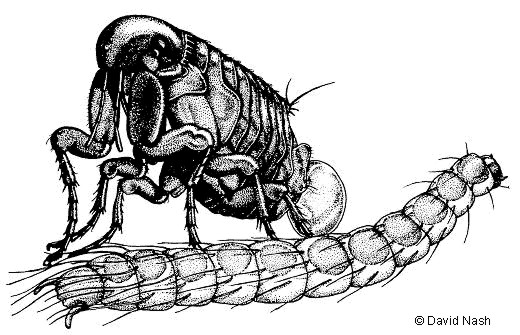

The drawing above shows an adult female Ceratophyllus gallinae laying an egg. In order to do start laying eggs, she needs to feed on the host several times. Unlike mammal fleas, which often remain on the host and feed for long periods, hen fleas spend most of their time among the material of the host's nest, and only hop on to the birds to feed for short periods.

The eggs laid by the female hatch into long, thin larvae, shown in the lower part of the drawing above. These feed on detritus amongst the nest material and on undigested blood which the adult fleas pass in their faeces. The larvae develop in a few weeks, and pupate inside a silk cocoon. Then they emerge as adults, mate and continue the cycle.

Reproduction can only take place when there are birds to feed on in the nest, so at the end of the host's breeding period those flea larvae that are left in the nest will spin their cocoons for pupation, and then remain in these throughout the summer, autumn and winter, as either larvae or pupae. If the nest is reused by birds the following year, then the pupae will hatch and the adults will mate, feed on the new hosts, and continue the cycle.

However, if the nest is not reused, the adults cannot feed and reproduce - then they will often hatch and make their way to the nest entrance (see below), where they may be able to disperse to a new nest, often by jumping onto a bird that is examining the old nest as a potential nest site.

Hen

fleas clustering around the entrance

to an unused nest box in Bern, Switzerland.

David Nash

www.zi.ku.dk/personal/drnash/index.html

Echidnophaga gallinacea si localizza nello spessore della cute degli uccelli. Dopo la fecondazione, le femmine si affondano nella cute della cresta e dei barbigli dove formano noduli in cui depositano le uova. Le larve, schiusesi dalle uova, cadono a terra per continuare il loro sviluppo. La pelle attorno ai noduli si ulcera e i giovani soggetti possono morire a causa di infestazioni gravi. La pulce può infestare anche i mammiferi (soprattutto il cane) e causa la formazione di noduli attorno agli occhi e negli spazi interdigitali.

Echidnophaga

gallinacea

sticktight flea

Taxonomic classification

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Insecta

Order: Siphonaptera

Genus: Echidnophaga gallinacea

Echidnophaga gallinacea is an international sticktight flea, which may infest a wide variety of birds and mammals. Echidnophaga gallinacea is the only species in the genus found in North America and mainly found in the southern United States. The flea was introduced accidentally due to humans and their domesticated animals. Echidnophaga gallinacea may infest an extremely wide range of hosts. It may become a serious pest of poultry and cause irritation to cats, dogs, rabbits, rodents, horses and humans.

Poultry may develop clusters of the fleas around the eyes, comb, wattles, and other bare spots. Echidnophaga gallinacea are difficult to remove because their heads are embedded in the host's flesh and they cannot be brushed off. The fleas may easily infest dogs and cats that frequently come in contact with barnyard fowl. Dog and cat infestations with sticktight fleas will usually be found around the margin of the outer ear or occasionally between the toe pads.

Host spectrum

Poultry, rodents, rabbits, canids, felids, horses, and occasionally humans may all become infested.

Geographic distribution

Echidnophaga gallinacea is found in the tropics, subtropics, and also in the United States as far north as Kansas and Virginia.

Morphology

Adults – The adults are approximately 1.5 to 4 mm in length and laterally flattened. They are dark brown in color, wingless, and have mouthparts that aid in both the piercing of the skin and sucking of the host’s blood. Neither genal nor pronotal combs are present. The adult fleas have heads that are flattened and angled acutely (not curved or rounded).The sticktight flea is one of the smallest fleas found on domestic animals.

Eggs – The eggs are approximately 0.5 mm in length. They are oval shaped and pearly white in color. Nonfertile females will produce eggs just as fertile females do, however, the eggs will be nonviable.

Larvae – The larvae are approximately 6 mm in length. They are maggot-like, creamy/yellow in color, and have thirteen segments with bristles on each segment.

Pupae - The pupa, with a loosely woven debris-collecting cocoon, is approximately 4 x 2 mm.

Life cycle

Before mating occurs both sexes will hop around freely. The life cycle is similar to that of Pulex irritans, except upon fertilization the females will remain attached to the host and lay their eggs in ulcers that have formed. The larvae will then fall off and feed on organic debris including the adult flea faeces. After many weeks the larvae will spin silken cocoons, becoming covered with dust and dirt, in which they pupate. An adult may emerge within days, weeks or even months depending on environmental conditions. The newly emerged adult fleas will seek a host, mate, and the females will attach to the host to produce another generation. The lifecycle requires approximately thirty to sixty days. Female sticktight fleas attach and feed at one site on their hosts for prolonged periods. These periods may range from four to nineteen days. During these feeding sessions, the surrounding tissue becomes swollen and ulcerated. Males will feed for shorter periods and look to mate around the same time.

Site of infestation

Echidnophaga gallinacea will attach to the skin (especially bare spots), around the eyes, comb, wattles, and anus

Pathogenesis/clinical signs

Echidnophaga gallinacea primarily cause problems in outdoor birds. The attached fleas will cause both swelling and ulceration. Young birds may die from infestation, due to anaemia produced by the fleas' feeding. The sheer numbers that may be present can make the eyes of the host swell shut, causing the host to starve to death.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Echidnophaga gallinacea is accomplished by finding the fleas on the host.

Treatment

Treatment of Echidnophaga gallinacea is difficult because the fleas are attached to the host. Sticktight fleas can be removed with tweezers by grasping and pulling firmly. In order to prevent infection, an antibiotic ointment should be applied to the area. If there are to many fleas to remove individually, a flea product registered for on-animal use should be applied according to label instructions. When applying the product, be careful not to come in contact with the host’s/animal's eyes. 5% malathion dust has also been effectively used for treatment.

Other control measures

Keep other hosts out of chicken pens, which can be a high area of flea infestation. To prevent reinfestation, treat the area to eliminate flea larval development. There are several insecticides registered for treatment of outdoor areas for fleas. Burning of infested organic material, such as animal bedding and poultry litter has also been a recommended form of treatment.

Public health significance

Echidnophaga gallinacea can infest humans. Although sticktight fleas are not known to transmit any diseases, their attachment can lead to problems such as secondary infections.