Lessico

Perside

In greco Persís,

in latino Persis/idis, antico persiano Parsa, neopersiano Fars.

Regione dell'antica Persia, sul Golfo Persico, culla e centro dell'impero

achemenide. Vi sorgevano le capitali Pasargade e Persepoli dove regnarono,

rispettivamente, Ciro![]() e Dario

e Dario![]() .

Sotto i Seleucidi fu la roccaforte della resistenza dei Persiani al dominio

ellenistico. Nel sec. II dC partì dalla Perside la riscossa nazionale e

religiosa dei Sassanidi, che condusse alla restaurazione dell'impero persiano.

.

Sotto i Seleucidi fu la roccaforte della resistenza dei Persiani al dominio

ellenistico. Nel sec. II dC partì dalla Perside la riscossa nazionale e

religiosa dei Sassanidi, che condusse alla restaurazione dell'impero persiano.

Fars è una delle 30 province dell'Iran. Si trova nel sud del Paese e ha per capoluogo Shiraz. Copre una superficie di 122.400 kmq. Nel 1996 la provincia contava circa 3.800.000 abitanti, dei quali il 58% inurbati.

Il Fars fu la sede originaria del popolo persiano. La lingua dell'Iran, il Farsi, prende il suo nome da questa provincia. Anche l'antico nome del Paese, Persia, deriva dalla forma greca, Persis, del nome originario della provincia Parsa.

I monti Zagros, che si estendono da nordovest a sudest, dividono la provincia in due distinte regioni geografiche, entrambe montuose. La provincia è divisa nei seguenti distretti: Estahban, Abadeh, Eqlid, Bavanat, Jahrom, Darab, Sepidan, Shiraz, Fasa, Firuzabad, Kazerun, Lar, Lamerd, Marvdasht, Mamasani, Khonj e Nayriz.

Il clima è freddo in inverno e tiepido in estate sulle montagne del

nordovest, mentre inverni miti e piovosi ed estati calde e secche si hanno

nella zona centrale. Nel sudest, infine, si hanno inverni temperati ed estati

torride. La temperatura media annuale di Shiraz è 16,8 °C, quella di gennaio

4,7 °C e di luglio 29,2 °C.

Culla della civiltà e della cultura persiane, il Fars fu il centro

dell'immenso impero achemenide, il primo impero persiano. Anche la dinastia

sassanide fondata da Ardashir I ebbe sede nella provincia.

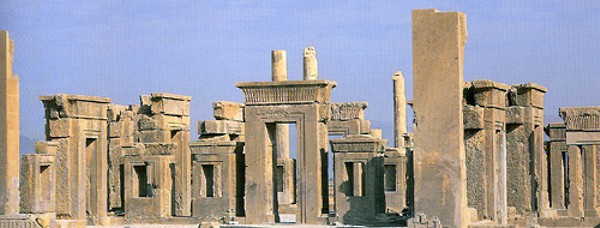

Le rovine di Persepoli, distrutta e incendiata da Alessandro Magno.

Durante la conquista araba, il Fars fu una delle province che resistette più strenuamente. Si arrese, infine, come il resto del Paese ai nuovi dominatori. In epoca islamica la provincia passò da una dinastia all'altra, da quella saffaride (IX secolo) a quella buwaihide (934-1062), da quella selgiuchide (XII secolo) a quella muzaffaride (XIV secolo), per essere infine sottomessa dai Safavidi ai primi del XVI secolo.

La posizione geografica, in prossimità del Golfo Persico, e la natura del territorio ha reso il Fars un luogo di stanziamento per diversi popoli provenienti da altre regioni, come Arabi, Turchi e, ovviamente, Iranici. Tuttavia la capacità delle originarie tribù del Fars di conservare l'unità della cultura e del proprio stile di vita costituisce parte di quell'eredità culturale iraniana che attrae i visitatori.

L'aeroporto di Shiraz è il maggiore della provincia. Le città di Lar e Lamerd hanno anch'esse aeroporti che le collegano a Shiraz, Tehran e ai Paesi del Golfo Persico come Emirati Arabi Uniti e Bahrain. Shiraz si trova lungo la strada principale da Teheran al sud dell'Iran.

I principali prodotti agricoli della provincia sono cereali (frumento e orzo), agrumi, datteri, barbabietole da zucchero e cotone. Industrie: petrolchimica, raffinerie di petrolio, produzione di pneumatici, elettronica e zuccherifici.

Il turismo è un settore importante dell'economia di Fars, come quello dell'artigianto: lavorazione dell'argento e ricamo a Shiraz, tessitura a Abadeh, ceramica a Estahban; fabbricazione di vari tipi di tappeti, jajim (lana e cotone) e kelim (pelo di capra) a Firuzabad.

Fars Province

Fars or Pars is one of the 30 provinces of Iran. It is in the south of the country and its center is Shiraz. It has an area of 122,400 km². In 1996, this province had a population of 3.8 million people, from which 56.7% were registered as urban dwellers, 41.0% villagers, and 1.4% nomad tribes.

Nominally, Fars is the original homeland of the Persian people. The native name of the Persian language is Farsi or Parsi. Persia and Persian both derive from the Hellenized form Persis of the root word Pars. The Old Persian word was Parsa.

Fars is located in the south of Iran. It neighbours Bushehr Province to the west, Hormozgan Province to the south, Kerman and Yazd provinces to the east, Isfahan province to the north and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province to the northwest.

There are three distinct climatic regions in the Fars Province. First, the mountainous area of the north and northwest with moderate cold winters and mild summers. Secondly, the central regions, with relatively rainy mild winters, and hot dry summers. The third region located in the south and southeast, has moderate winters with very hot summers. The average temperature of Shiraz is 16.8 °C, ranging between 4.7° and 29.2 °C.

The geographical and climatic variation of the province causes varieties of plants, consequently, variation of wild life has been formed in the province. Additional to the native animals of the province, many kinds of birds migrate to the province every year. Many kinds of ducks, storks and swallows migrate to this province in annual period. The main native animals of the province are gazelle, deer, mountain wild goat, ram, ewe and many kinds of birds. The province of Fars includes many protected wild life zones. The most important protected zones are as following:

Toot Siah (Black Berry) Hunt Forbidden Zone, which is located at the end of

Boanat region.

Basiran Hunt Forbidden Zone which is located 4 kilometers south to Abadeh.

Bambo National Park which is located on the north of Shiraz.

Estahban Forest Park ( Parke Jangaly) which is located on the outskirts of

Touraj mountain.

Hermoodlar Protected Zone which is located east to larestan.

History

Pre-Islamic era

The ruins of Persepolis

A branch of the Indo-Iranians migrated to Fars in the second millennium BC. The ancient Persians became the rulers of a large empire under the Achaemenid Empire in the sixth century BC. The ruins of Persepolis and Pasargadae, two of the four capitals of the Achaemenid Empire, are located in Fars. The Achaemenid Empire was defeated by Alexander the Great in the fourth century BC. The Seleucid Empire was defeated by the Parthians in 238 BC.

Babak was the ruler of a small town called Kheir. Babak's efforts in gaining local power at the time escaped the attention of Artabanus IV, the Arsacid Emperor of the time. Babak and his eldest son Shapur managed to expand their power over all of Persis.

The subsequent events are unclear, due to the sketchy nature of the sources. It is however certain that following the death of Babak around 220, Ardashir who at the time was the governor of Darabgird, got involved in a power struggle of his own with his elder brother Shapur. The sources tell us that in 222 Shapur was killed when the roof of a building collapsed on him.

A Sassanid relief showing the investiture of Ardashir I

At this point, Ardashir moved his capital further to the south of Persis and founded a capital at Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly Gur, modern day Firouzabad).

After establishing his rule over Persis, Ardashir I rapidly extended his territory, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighboring provinces of Kerman, Isfahan, Susiana, and Mesene.

Artabanus marched a second time against Ardashir I in 224. Their armies clashed at Hormizdeghan, where Artabanus IV was killed. He was crowned in 226 at Ctesiphon as the sole ruler of Persia; bringing the 400-year-old Parthian Empire to an end. The Sassanids ruled for 425 years, until the Arab armies conquered the empire.

Islamic era

The cities of Fars province put up a firm resistance to the Arabs during the Islamic Conquest of Iran, particularly in areas around Istakhr. The province however, as well as most of Persia ultimately fell to the conquest. Fars then passed hand to hand through numerous dynasties, leaving behind numerous historical and ancient monuments; each of which has its own values as a world heritage, reflecting the history of the province, Iran, and western Asia. The ruins of Bishapur, Persepolis, and Firouzabad are all reminders of this.

Economy

Agriculture is of great importance in Fars. The major products include cereal (wheat and barley), citrus fruits, dates, sugar beets and cotton. Fars has major petrochemical facilities, along with an oil refinery, a factory for producing tires, a large electronics industry, and a sugar mill.

Persia antica

dalle origini al XVIII secolo

Dal 22 marzo 1935 il Paese ha assunto ufficialmente il nome di Iran, mentre in precedenza veniva chiamato anche Persia (dal persiano antico Parsa, regione in cui si trovava il regno di Ansan). Tale nome venne diffuso dagli storici antichi per indicare l'impero achemenide, e ha tuttora larga diffusione nel mondo occidentale. L' Iran, prima di essere occupato dalle tribù ariane, fu sede nella sua parte occidentale del regno elamita con capitale a Susa, che durante il II millennio aC, sotto influenze mesopotamiche, ebbe una parte culturale importante fra la valle del Tigri, la catena degli Zagros e il litorale del Golfo Persico.

Le tribù indeuropee, le cui prime sedi furono probabilmente le steppe della

Russia meridionale e della Transcaucasia, mossero verso sud intorno alla metà

del II millennio. Fra le tribù di stirpe iranica stanziatesi nella parte

occidentale dell'altopiano emergono per importanza gli Sciti, la cui

supremazia fu di breve durata, i Medi, già citati negli annali assiri

nell'836 aC, il cui regno, con capitale Ecbatana![]() , giunse dall'Elam all'Urartu,

e principalmente i Persiani Achemenidi.

, giunse dall'Elam all'Urartu,

e principalmente i Persiani Achemenidi.

Questi ultimi, dapprima sovrani di un piccolo regno nella regione di Parsa,

semindipendente sotto Assiri ed Elamiti, e poi vassallo dei Medi, giunsero a

dominare in breve tempo quasi tutto il mondo antico, particolarmente sotto

Ciro il Grande![]() e Dario I

e Dario I![]() (sec. VI-V aC), coi quali l'impero achemenide si

estese dalla Tracia e dall'Egitto a occidente sino al Gandhara e alla valle

dell'Indo a oriente.

(sec. VI-V aC), coi quali l'impero achemenide si

estese dalla Tracia e dall'Egitto a occidente sino al Gandhara e alla valle

dell'Indo a oriente.

Tale impero, caratterizzato da una cultura composita e cosmopolita, grandiosa

sintesi delle antiche civiltà della Mesopotamia, Siria, Egitto e Asia Minore,

nel sec. IV aC cadde in pochi anni sotto i colpi di Alessandro Magno![]() , che aprì

la strada a una profonda ellenizzazione sia politica sia culturale dell' Iran,

continuata sotto i Seleucidi. Presero quindi il sopravvento sull'altopiano

iranico i Parti (sec. II aC-III dC), originari del Khorasan, mentre l'estremità

orient. dell' Iran era dominata, nei primi due secoli della nostra era, dal

regno dei Kusana.

, che aprì

la strada a una profonda ellenizzazione sia politica sia culturale dell' Iran,

continuata sotto i Seleucidi. Presero quindi il sopravvento sull'altopiano

iranico i Parti (sec. II aC-III dC), originari del Khorasan, mentre l'estremità

orient. dell' Iran era dominata, nei primi due secoli della nostra era, dal

regno dei Kusana.

Una reazione nazionale iranica fu costituita dal sorgere della dinastia sassanide (sec. III-VII), originaria del Fars, il cui impero fortemente centralizzato, con capitale a Ctesifonte in Mesopotamia, è segnato da un riassorbimento degli elementi ellenistici penetrati in Iran nelle epoche precedenti e da una rinascita delle tradizioni nazionali e della religione mazdea.

La conquista araba (634-651) inserì l' Iran nell'impero musulmano che si andava creando nei primi anni dopo la morte di Maometto, diffondendo nel Paese l'Islam che sostituì quasi del tutto l'antica religione zoroastriana. Sotto i califfi omayyadi (661-750), che governavano da Damasco, l' Iran rimase in posizione alquanto marginale, mentre riacquistò la sua importanza col califfato degli Abbasidi, la cui ascesa si dovette soprattutto a elementi iranici, e che posero la loro capitale a Baghdad, sul territorio dell'antico impero sassanide.

Con la disgregazione politica dell'impero califfale si vennero affermando a

partire dal sec. IX in varie zone dell' Iran dinastie locali, fra cui i

Tahiridi (820-872) nel Khorasan e Transoxiana, coi loro successori Saffaridi

(868-908), e particolarmente i Samanidi (874-999), che fondarono un vasto e

importante Stato dal Khorasan![]() e Sistan sino a Taskent. Tali Stati, in seguito

a scismi religiosi e alla pressione delle popolazioni centro-asiatiche,

dovettero cedere a dinastie di origine turca, quali i Gasnavidi (sec. X-XII)

con centro in Afghanistan, e i Selgiuchidi (sec. XI-XIII) che formarono un

vasto regno comprendente Iran e Asia Minore, o di origine mongola: tali furono

gli Ilkhanidi, successori di Hülägü, che governarono vaste zone dell' Iran

sotto la sovranità del Gran Khan dei Mongoli, e i Timuridi.

e Sistan sino a Taskent. Tali Stati, in seguito

a scismi religiosi e alla pressione delle popolazioni centro-asiatiche,

dovettero cedere a dinastie di origine turca, quali i Gasnavidi (sec. X-XII)

con centro in Afghanistan, e i Selgiuchidi (sec. XI-XIII) che formarono un

vasto regno comprendente Iran e Asia Minore, o di origine mongola: tali furono

gli Ilkhanidi, successori di Hülägü, che governarono vaste zone dell' Iran

sotto la sovranità del Gran Khan dei Mongoli, e i Timuridi.

Una riscossa “nazionale” si ebbe, sotto le bandiere sciite, con i Safavidi (1502-1736). Il fondatore della dinastia, Ismail I, dopo una successione di rapide conquiste, cozzò invano contro l'ostacolo ottomano: di esso venne invece brillantemente a capo Abbas I nei primi anni del Seicento grazie a un esercito organizzato all'europea. Ma dopo la morte di Abbas I seguì un periodo di rapido declino: Baghdad, Armenia e Kurdistan furono recuperati dai Turchi.

Nel 1722 gli Afghani saccheggiarono Esfahan, la capitale. L'impero persiano perse le sue province caucasiche, divise tra Turchi e Russi. La potenza dell' Iran appariva al tramonto, allorquando Nadir Shah, un soldato di ventura, riuscì a risollevarne le sorti. Afgani, Turchi e Russi furono sconfitti o costretti con le minacce ad abbandonare i territori strappati. Successivamente Nadir invase l'India (1739) e annetté l'Afghanistan e le regioni a ovest dell'Indo; si rivolse poi a nord conquistando Khiva e Bukhara. Alla morte di Nadir (1747) il vasto impero andò in pezzi. I successori di Nadir, gli Zand e i Cagiari (1786-1925) non raccolsero che una parte della sua eredità: inoltre dovettero ben presto fare i conti con la duplice pressione russa e inglese. Nel 1828 le regioni caucasiche furono definitivamente cedute alla Russia, mentre l'Inghilterra impedì ai Persiani di riconquistare l'Afghanistan (1857).

Ancient Persia

The name Persia (from the ancient province of Persis; modern Fars, Iran) was given by the Greeks to the entire land occupied by various Iranian tribes from which the Achaemenid dynasty arose. It is the land of present-day Iran and Afghanistan, geographically the Iranian plateau.

The earliest inhabitants of this area are only known, at first, from their stone artifacts and, later, their pottery. Paleolithic and Neolithic sites have been found in various parts of the plateau, but distinctive painted pottery appears only in the Chalcolithic Period, about 3000 BC. In sites such as Tepe Sialk, Tepe Hissar, and Tepe Giyan similar painted pottery has been found, indicating early connections among the inhabitants.

More is known about the material culture of the peoples on the plateau in the 3d millennium BC, but the various groups assume an historical identity only with the advent of written records in cuneiform. In the south were the Elamites, whose principal city, Susa, was on the plain of Mesopotamia. The Elamite language has not been fully deciphered, but it was unlike any of the later languages of the region. In the 2d millennium BC the Elamites were found throughout southern Iran.

To the north in the mountains lived Kassites who also descended onto the plains of Mesopotamia. In present-day Azerbaijan province lived people called Manneans. South of the sea that bears their name lived the Caspians.

Thus the western part of the Iranian plateau was inhabited by various peoples whose relationships to each other and whose languages are hardly known. The art objects of these peoples, some of which are made of gold and silver, reveal the high material culture then existing. Bronze objects from Luristan, mostly from graves, are evidence of great artistic originality. In eastern Iran archaeological excavations are only beginning to reveal evidence of settlements and civilization.

By the end of the 2d millennium BC invaders from the north had begun to spread over the Iranian plateau. These were Indo-European speakers, one branch of which invaded the subcontinent of India while their close relatives the Iranians penetrated the plateau. Both the Indians and Iranians called themselves Aryans. They had war chariots pulled by horses, but the Iranians soon found that cavalry was more effective in mountain areas. By the 9th century they had entered the Zagros Mountains; the Medes, the most prominent of the Iranian peoples, are mentioned as being there by Assyrian sources in 836 BC. More than a century later the Parsa, or Persians, appeared in the south. Other Iranian tribes spread over the entire plateau.

The Median Kingdom

The first kingdom, which was a federation of tribes, created by the Iranians, about 700 BC, was that of the Medes in western Iran. The rise of Media was hindered by invasions from north of the Caucasus Mountains, first by a Thracian people called Cimmerians, followed by Iranian nomads called Scythians. About 625 BC a new attempt was made by the Medes under Cyaxares to form a united kingdom, and after defeating the Scythians, the Medes turned against Assyria. An alliance was made between the Babylonians and the Medes, and the allies stormed and destroyed the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, in 612 BC, a date used today by the Kurds, who claim descent from the Medes, to begin their Kurdish era of time reckoning.

The Achaemenids

The Medes also subdued the Persians and other Iranians on the plateau, but the Median empire lasted only until 549, when the last Median king, Astyages (r. 584-549), was defeated by his Persian vassal Cyrus The Great, who became the heir of the Median king and ruled an even greater empire from 549 to 530 BC. His son Cambyses II, who ruled from 530 to 522, invaded Egypt. Following an interregnum of a year, Darius I took power by killing the usurper Smerdis and established the Achaemenid empire on a firm basis. He consolidated and further extended Persian conquests (so that the empire stretched from Egypt and Thrace in the west to northwestern India in the east); established the system of satraps (local governors) under firm centralized control; encouraged the spread of Zoroastrianism; and was a great patron of the arts. Darius's son Xerxes I (r. 486-465), after his defeat by the Greeks in the Persian Wars, retired from active government and set a precedent for future kings who were kept in power by the efficient bureaucracy organized by Darius.

Constant revolts were put down, but the weakness of the empire was apparent under Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424), Xerxes II (r. 424-423), and Darius II (r. 423-404). Under Artaxerxes II (r. 404-359), the revolt of his brother Cyrus The Younger almost cost him his throne. Artaxerxes III (r. 359-338), an able although cruel monarch, saved the empire from disintegration by reconquering the provinces of Phoenicia and Egypt, which had previously regained their independence. Unfortunately for the Achaemenid empire, Artaxerxes III was poisoned, and a puppet Arses ruled for two years. The last prince of the Achaemenid family, Darius III Codomannus, assumed the throne in 336. He was defeated twice by Alexander The Great and was murdered by his own followers in 330.

The Seleucids

In the fighting among Alexander's successors, the Diadochi, Iran fell to Seleucus I, who created a new era of time reckoning by his march into Babylon in 312 BC. The Seleucids established many Greek settlements in the east, and under them Hellenism mixed with local cultures to form a syncretic civilization in Iran. The Seleucids never controlled all of the Iranian plateau, and the south, present-day Fars province, was ruled by an independent local dynasty with the title frataraka. In the northern province of Azerbaijan, a Persian satrap from the Achaemenid period called Atropates established a local dynasty and gave his name to the province. In the east the Greeks who settled in Bactria established an independent kingdom about 246 BC, and the Parthians declared their independence from Seleucid rule about the same time.

Although the Seleucids were able temporarily to regain the allegiance of both sets of rebels during the reign of Antiochus III (r. 223-187 BC), the Parthians were to emerge as their heirs.

The Parthians

The Arsacids, rulers of the Parthians, called themselves phil-Hellene on their coins, and they continued using Greek until the end of the dynasty in AD 224. The Parthians were famous as cavalry soldiers with bows and arrows against the Romans, and they lived in a feudal society. The many small courts of the nobility provided the background for the development of the Persian national epic, which is filled with stories about heroes from the Parthian period. Under the Parthians many small kingdoms existed in uneasy allegiance to an Arsacid king of kings. Among the vassal kingdoms ruled by Arsacid princes was Armenia. The Parthians had to fight the Romans in the west and the Sakas, or Scythians, followed by the Kushans in the east. The lack of unity among the Parthian princes aided the rise of the Sassanian dynasty.

The Sassanians

The Sassanians were not phil-Hellene like their predecessors but sought to establish a national Persian renaissance in both culture and ideology. From the outset Ardashir I, who killed his Parthian overlord in AD 224, proclaimed a revival of ancient glory, although the Sassanians had only the faintest memory of the Achaemenids. The early buildings of Ardashir in Fars province were massive, proclaiming imperial grandeur. The centralization of power in the hands of the king of kings was the opposite of the Parthian period of history. After Shapur I's victory over the Romans and capture of the Emperor Valerian in 260, he proclaimed his power in a series of rock relieves in Fars depicting his victories. Roman prisoners were employed in building dams and irrigation projects in various parts of the Sassanian empire. During Shapur's reign Zoroastrianism became the official state religion.

Shapur's successors--his son Hormizd Ardashir (r. 272-73), another son Bahram I (r. 273-76), his grandson Bahram II (r. 276-93), and another son Nerseh (r. 293-302)--all sought to strengthen dynastic power as opposed to the nobility. Under Hormizd II (r. 302-09), Shapur II (r. 309-79), Ardashir II (r. 379-83), Shapur III (r. 383-88), and Bahram IV (r. 388-99), wars with Rome alternated with struggles against nomadic invaders from the east. Yazdegird I (r. 399-421) relaxed the persecution against Christians, who had been suspected of having been secret allies of the Romans since Shapur II. Bahram V (r. 421-39) was surnamed Gur because of his skill in hunting the onager. Many stories are told about him in the national epic, Shah Namah, by Firdawsi and elsewhere. Yazdegird II (r. 439-57), Hormizd III (r. 457-59), Peroz (r. 459-84), and Balash (r. 484-88) had difficulties with the Hephthalites (White Huns) in present-day Afghanistan. Under Kavad (r. 488-531) and his brother Zamasp (r. 496-98), a communistic socioreligious movement led by the "prophet" Mazdak gained adherents. It was savagely suppressed by Khosru I (r. 531-79), who has been called the greatest ruler of the dynasty. Hormizd IV (r. 579-90) was followed by Bahram Chobin (r. 590-91), the only successful rebel against the Sassanian house. He was overthrown by Khosru II (r. 591-628), the last great Sassanian ruler. Khosru II tried to reestablish the frontiers of the Achaemenid empire, but initial success was followed by defeat at the hands of the Byzantine emperor Heraclius and assassination. A succession of rulers culminated in Yazdegird III (r. 632-51), under whom the exhausted Sassanian empire succumbed to the attacks of the Muslim Arabs.

Richard N. Frye

Bibliography: Boyle, J. A., ed., Persia: History and Heritage (1978); Cameron, George G., History of Early Iran (1976); Frye, R. N., The Heritage of Persia, 2d ed. (1976); Girshman, Roman, et al., Persia, The Immortal Kingdom (1971); Herzfeld, E. E., Archaeological History of Iran (1976); Hicks, Jim, The Persians (1975); Irving, Clive, Crossroads of Civilization: Three Thousand Years of Persian History (1979); Olmstead, A. T. E., History of the Persian Empire, 2d ed. (1969); Zaehner, R. C., The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism (1961).

Grolier Encyclopedia – 1992

Tomba di Ciro II a Pasargade

Pasargade è un'antica città dell'Iran, circa 50 km a NE di Persepoli, fondata intorno alla metà del sec. VI aC da Ciro nel luogo della sua vittoria sui Medi. Prese il nome della tribù dei Pasargadi alla quale appartenevano gli Achemenidi, la famiglia cioè di Ciro e di Dario. Pasargade fu la capitale di Ciro, che vi costruì il suo palazzo e la sua tomba , e rimase, dopo il trasferimento della capitale a Persepoli, la città dove avveniva la cerimonia dell'investitura dei re persiani. Il palazzo comprendeva un ingresso, una grande sala delle udienze (apadana) e una per i banchetti, cioè tutti gli elementi necessari alla vita di rappresentanza del sovrano. Un tempio del fuoco è da identificarsi nella costruzione quadrata detta Zindan-i Sulaiman. Ben conservata è la tomba di Ciro, cella rettangolare che poggia su un basamento a sei gradoni di altezza decrescente dal basso in alto.

Pasargadae

Pasargadae was a city in ancient Persia, and is today an archaeological site and one of Iran's UNESCO World Heritage Sites. According to the Elamite cuneiform of the Persepolis fortification tablets the name was rendered as Batrakataš, and the name in current usage derives from a Greek transliteration of an Old Persian Pâthragâda toponym of still-uncertain meaning.

Its ruins lie 87 km (54 mi) northeast of Persepolis, in present Fars province of Iran, and was the first capital of the Achaemenid Empire. The construction of the capital city by Cyrus the Great, begun in 546 BC or later, was left unfinished, for Cyrus died in battle in 530 BC or 529 BC. Pasargadae remained the Persian capital until Darius began assembling another in Persepolis. The modern name comes from the Greek, but may derive from an earlier one used during Achaemenid times, Pâthragâda.meaning the garden of Pars

The archaeological site covers 1.6 square kilometres and includes a structure commonly believed to be the mausoleum of Cyrus, the fortress of Toll-e Takht sitting on top of a nearby hill, and the remains of two royal palaces and gardens. The gardens provide the earliest known example of the Persian chahar bagh, or four-fold garden design. (See Persian Gardens.)

Latest research on Pasargadae’s structural engineering has shown the Achaemenid engineers constructed the city to withstand a severe earthquake, at what would today be classified as a '7.0' on the Richter magnitude scale. The foundations are today classified as having a "Base Isolation" design, much the same as what is presently used in countries for the construction of facilities - such as nuclear power plants - that require insulation from the effects of a seismic activity.

The monument generally assumed to be the tomb of Cyrus the Great

The most important monument in Pasargadae is the tomb of Cyrus the Great. It has six broad steps leading to the sepulchre, the chamber of which measures 3.17 m long by 2.11 m wide by 2.11 m high, and has a low and narrow entrance. Though there is no firm evidence identifying the tomb as that of Cyrus, Greek historians tell us that Alexander the Great believed it was so. When Alexander looted and destroyed Persepolis, he paid a visit to the tomb of Cyrus. Arrian, writing in the second century of the common era, recorded that Alexander commanded Aristobulus, one of his warriors, to enter the monument. Inside he found a golden bed, a table set with drinking vessels, a gold coffin, some ornaments studded with precious stones and an inscription of the tomb. No trace of any such inscription survives to modern times, and there is considerable disagreement to the exact wording of the text. Strabo reports that it read:

Passer-by, I am Cyrus, who gave the Persians an empire, and was king of Asia.

Grudge me not therefore this monument.

Another variation, as documented in Persia: The Immortal Kingdom, is:

O man, whoever thou art, from wheresoever thou cometh, for I know you shall

come, I am Cyrus, who founded the empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not, therefore, this little earth that covers my body.

According to some classicists, the style and construction of the tomb show strong connections with Anatolian tombs of a similar period. In particular, the tomb at Pasargadae has almost exactly the same dimensions as the tomb of Alyattes II, father of the Lydian King Croesus; however, many have refused the claim, (According to Herodotus, Croesus was spared by Cyrus during the conquest of Lydia, and became a member of Cyrus' court.) Some[attribution needed] scholars believe that Cyrus may have "imported" Lydian stonemasons for the construction of the tomb. In general, the art and architecture found at Pasargadae exemplified the Persian synthesis of various traditions, drawing on precedents from Elam, Babylon, Assyria, and ancient Egypt, with the addition of some Anatolian influences.

During the Islamic conquest of Iran, the Arab armies came upon the tomb and planned to destroy it, considering it to be in direct violation of the tenets of Islam. The caretakers of the grave managed to convince the Arab command that the tomb was not built to honor Cyrus, but instead housed the mother of King Solomon, thus sparing it from destruction. As a result, the inscription in the tomb was replaced by a verse of the Qur'an, and the tomb became known as "Qabr-e Madar-e Sulaiman," or the tomb of the mother of Solomon. It is still widely known by that name today.

There has been growing concern regarding the proposed Sivand Dam, named after the nearby town of Sivand. Despite planning that has stretched over 10 years, Iran's own Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization was not aware of the broader areas of flooding during much of this time.

Its placement between both the ruins of Pasargadae and Persepolis has many archaeologists and Iranians worried that the dam will flood these UNESCO World Heritage sites, although scientists involved with the construction say this is impossible because the sites sit well above the planned waterline. Of the two sites, Pasargadae is the one considered the most threatened.

The broadly shared concern by archaeologists is the effect of the increase in humidity caused by the lake; experts from the Ministry of Energy however believe it would be compensated by controlling the water level of the dam reservoir. All agree that humidity created by it will speed up the gradual destruction of Pasargadae. Construction of the dam began April 19, 2007.

In greco Persépolis, in persiano Parsa. Antica città della

Persia le cui rovine sorgono 60 km a NE della città iraniana di Shiraz. La

costruzione della città fu iniziata da Dario I![]() nel 518 aC. e proseguita da

Serse I

nel 518 aC. e proseguita da

Serse I![]() e Artaserse I

e Artaserse I![]() e III; fu distrutta da un incendio provocato da

Alessandro Magno

e III; fu distrutta da un incendio provocato da

Alessandro Magno![]() nel 330 aC.

nel 330 aC.

Le sue rovine sorgono su una grande terrazza costruita con blocchi rettangolari cui si accede mediante una scalinata. L'ingresso ai palazzi reali avviene attraverso la monumentale porta di Serse. L'Apadana, o sala delle udienze, a sua volta costruita su di un terrapieno, è formata da un ambiente quadrato con sei file di colonne rastremate ornate da capitelli zoomorfi e da portici con colonne sui lati nord, est e ovest. Le sue scalinate di accesso sono ornate, nel lato nord, da rilievi con schiere di guardie imperiali mede e persiane; sul lato est da un corteo di sudditi di vari Paesi che recano tributi al sovrano.

Dietro l'Apadana sono il tripylon, sala quadrata a tre porte, il palazzo dei banchetti di Dario, quello di Serse e altri edifici. Sul lato est sorgono la sala delle Cento Colonne, gli ambienti per le guardie imperiali e la tesoreria. Il complesso si completa con le tombe di Artaserse II e III scavate sull'adiacente monte Rahmat e con quelle di Naqsh-i-Rustam, a pochi chilometri di distanza.

Persepolis

The ruins of Persepolis

Persepolis (Old Persian: 'Pars', New Persian: Takht-e Jamshid) was an ancient ceremonial capital of the second Iranian dynasty, the Achaemenid Empire. It was built during the reign of King Darius I around 515 BC. The largest and most complex building in Persepolis was the audience hall, or Apadana with 72 columns. Persepolis is situated some 70 km northeast of the modern city of Shiraz in the Fars Province of Iran. In contemporary Iran the site is known as Takht-e Jamshid (Throne of Jamshid). To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Parsa, meaning The City of Persians, Persepolis being the Greek interpretation of the name Perses (meaning Persian) + polis (meaning city).

Location of Persepolis

Archaeological evidence shows the earliest remains of Persepolis date from around 515 BC. André Godard, the French archaeologist who excavated Persepolis in the early 1930s, believed that it was Cyrus the Great who chose the site of Persepolis, but it was Darius the Great who built the terrace and the great palaces.

Darius ordered the construction of Apadana Palace and the Debating hall (Tripylon or the three-gated hall), the main imperial Treasury and its surroundings, which were completed at the time of the reign of his son, King Xerxes I. Further construction of the buildings at the terrace continued until the downfall of the Achaemenid dynasty.

The first westerner to visit Persepolis was Antonio de Gouveia from Portugal who wrote about cuneiform inscriptions following his visit in 1602. His first written report on Persia, the "Jornada", was published in 1606. The first scientific excavation at Persepolis was carried out by Ernst Herzfeld in 1931, commissioned by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. He believed the reason behind the construction of Persepolis was the need for a majestic atmosphere, as a symbol for their empire and to celebrate special events, especially the “Nowruz”, (the Iranian New Year held on 21 March). For historical reasons and deep rooted interests it was built on the birthplace of the Achaemenid dynasty, although this was not the centre of their Empire at that time.

The main characteristic of Persepolitan architecture is its columns, which were made of wood. Only when even the largest cedars of Lebanon or the teak trees of India did not fulfill the required sizes did the architects resort to stone. The bases and the capitals were always of stones, even on wooden shafts, but the existence of wooden capitals is probable.

The remains including the bas-reliefs and sculptures provide an insight into hearts and beliefs of the ancient Iranians. The buildings at Persepolis are divided into three areas; military quarters, the treasury and the reception and occasional houses for the King of Kings. These included the Great Stairway, the Gate of Nations (Xerxes), the Apadana palace of Darius, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and Tachara palace of Darius, the Hadish palace of Xerxes, the palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables and the Chariot house.

Persepolis is near the small river Pulwar which flows into the Kur (Kyrus). The site is marked by a large 125,000 square meter terrace, partly artificially constructed and partly cut out of a mountain, with its east side leaning on Kuh-e Rahmet ("the Mountain of Mercy"). The other three sides are formed by retaining walls, which varies in height with the slope of the ground. From 5 to 13 meters on the west side there is a double stair, gently sloping, which leads to the top. To create the level terrace, any depressions that were present were filled up with soil and heavy rocks. They joined the rocks together with metal clips.

Gray limestone was the main material used in building Persepolis. To reach the top terrace, the construction of a broad Stairway, 20 meters above the ground, was planned to be the only main entrance. This was begun around 518 BC. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan stairway, was built in a symmetrical manner on the western side of the Great Wall. The 111 steps were 6.9 meters wide with treads of 31 centimeters and rises of 10 centimeters. Originally the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback, new theories suggest that this was to allow visiting dignitaries to in fact walk up the stairs while keeping a regal appearance, permissible by the ease in which the stairs could be climbed due to the small distance between each step.

The top of the stairways led to a small yard in the northeastern side of the terrace, opposite the Gate of Nations. After natural rock had been leveled and the depressions filled in, the terrace was prepared. Major tunnels for sewage were dug underground through the rock. A large elevated water storage tank was carved at the eastern foot of the mountain. Professor Olmstead suggested the cistern was constructed at the same time the construction of the towers began.

The uneven plan of part of the foundation of the terrace acted like a castle whose angled walls enabled its defenders to target any section of the external front. Diodorus writes that Persepolis had three walls with ramparts, which all had towers to provide protection space for the defense personnel. The first wall was 7 meters tall, the second, 14 meters and the third wall, which covered all four sides, was 27 meters in height, though no presence of the wall exists in modern times.

On this terrace are the ruins of a number of colossal buildings, all constructed of dark-grey marble from the adjacent mountain. A few of the remaining pillars are still intact, standing in the ruins. Several of the buildings were never finished. F. Stolze has shown that in some cases even the mason's rubbish has not been removed. These ruins, for which the name Chehel minar ("the forty columns or minarets"), can be traced back to the 13th century, are now known as Takht-e Jamshid ("the throne of Jamshid"). That they represent the Persepolis captured and partly destroyed by Alexander the Great has been beyond dispute at least since the time of Pietro della Valle.

Behind Takht-e Jamshid are three sepulchres hewn out of the rock in the hillside. The facades, one of which is incomplete, are richly decorated with relieves. About 13 km NNE, on the opposite side of the Pulwar, rises a perpendicular wall of rock, in which four similar tombs are cut, at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley. The modern Persians call this place Naqsh-e Rustam - or Nakshi Rostam ("the picture of Rostam"), from the Sassanian reliefs beneath the opening, which they take to be a representation of the mythical hero Rostam. That the occupants of these seven tombs were kings might be inferred from the sculptures, and one of those at Nakshi Rustam is expressly declared in its inscription to be the tomb of Darius Hystaspis, concerning whom Ctesias relates that his grave was in the face of a rock, and could only be reached by the use of ropes. Ctesias mentions further, with regard to a number of Persian kings, either that their remains were brought "to the Persians," or that they died there.

The Gate of all Nations, referring to subjects of the empire, consisted of a grand hall that was almost 25 square metres, with four columns and its entrance on the Western Wall. There were two more doors, one to the south which opened to the Apadana yard and the other one opened onto a long road to the east. Pivoting devices found on the inner corners of all the doors indicate that they were two-leafed doors, probably made of wood and covered with sheets of ornate metal.

A pair of Lamassu's,which are bulls with the head of a bearded man stand on the western threshold, and another pair with wings and a Persian head (Gopät-Shäh) on the eastern entrance, to reflect the Empire’s power. Xerxes' name was written in three languages and carved on the entrances, informing everyone that he ordered this to be built.

The Apadana Palace, northern stairway (detail)

Darius the Great built the greatest and most glorious palace at Persepolis in the western side. This palace was named Apadana and was used for the King of Kings' official audiences. The work began in 515 BC and was completed 30 years later, by his son Xerxes I. The palace had a grand hall in the shape of a square, each side 60m long with seventy-two columns, thirteen of which still stand on the enormous platform. Each column is 19 m high with a square Taurus and plinth. The columns carried the weight of the vast and heavy ceiling. The tops of the columns were made from animal sculptures such as two headed bulls, lions and eagles. The columns were joined to each other with the help of oak and cedar beams, which were brought from Lebanon. The walls were covered with a layer of mud and stucco to a depth of 5cm, which was used for bonding, and then covered with the greenish stucco which is found throughout the palaces. At the western, northern and eastern sides of the palace there was a rectangular veranda which had twelve columns in two rows of six. At the south of the grand hall a series of rooms were built for storage. Two grand Persepolitan stairways were built, symmetrical to each other and connected to the stone foundations. To avoid the roof being eroded by rain vertical drains were built through the brick walls. In the Four Corners of Apadana, facing outwards, four towers were built.

The Walls were tiled and decorated with pictures of lions, bulls, and flowers.

Darius ordered his name and the details of his empire to be written in gold

and silver on plates, and to place them in covered stone boxes in the

foundations under the Four Corners of the palace. Two Persepolitan style

symmetrical stairways were built on the northern and eastern sides of Apadana

to compensate for a difference in level. There were also two other stairways

in the middle of the building. The external front views of the palace were

embossed with pictures of the Immortals, the Kings' elite guards. The northern

stairway was completed during Darius' reign, but the other stairway was

completed much later.

Ruins of Throne Hall

Next to the Apadana, second largest building of the Terrace and the final edifices, is the Throne Hall or the Imperial Army's hall of honour (also called the "Hundred-Columns Palace). This 70x70 square meter hall was started by Xerxes and completed by his son Artaxerxes I by the end of the fifth century BC. Its eight stone doorways are decorated on the south and north with reliefs of throne scenes and on the east and west with scenes depicting the king in combat with monsters. In addition, the northern portico of the building is flanked by two colossal stone bulls.

In the beginning of Xerxes's reign the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for military commanders and representatives of all the subject nations of the empire, but later the Throne Hall served to be as an imperial museum.

There were other palaces built, these included the Tachara palace which was built under Darius I, the Imperial treasury which was started by Darius in 510 BC and finished by Xerxes in 480 BC. The Hadish palace by Xerxes I, which occupies the highest level of terrace and stand on the living rock. The Council Hall, the Tryplion Hall, The Palaces of D, G, H, Storerooms, Stables and quarters, Unfinished Gateway and a few Miscellaneous Structures at Persepolis near the south-east corner of the Terrace, at the foot of the mountain.

It is commonly accepted that Cyrus the Great was buried at Pasargadae. If there is any truth in the statement that the body of Cambyses II was brought home "to the Persians", his burying-place must be sought somewhere beside that of his father. Ctesias assumes that it was the custom for a king to prepare his own tomb during his lifetime. Hence the kings buried at Naghsh-e Rustam are probably Darius the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II. Xerxes II, who reigned for a very short time, could scarcely have obtained so splendid a monument, and still less could the usurper Sogdianus (Secydianus). The two completed graves behind Takhti Jamshid would then belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The unfinished one is perhaps that of Arses of Persia, who reigned at the longest two years, or, if not his, then that of Darius III (Codomannus), who is one of those whose bodies are said to have been brought "to the Persians."

Another small group of ruins in the same style is found at the village of Hajjiäbäd, on the Pulwar, a good hour's walk above Takhti Jamshid. These formed a single building, which was still intact 900 years ago, and was used as the mosque of the then existing city of Istakhr.

Since Cyrus the great was buried in Pasargadae, which is mentioned by Ctesias as his own city, and since, to judge from the inscriptions, the buildings of Persepolis commenced with Darius I, it was probably under this king, with whom the sceptre passed to a new branch of the royal house, that Persepolis became the capital of Persia proper. As a residence, however, for the rulers of the empire, a remote place in a difficult alpine region was far from convenient, and the real capitals were Susa, Babylon and Ecbatana. This accounts for the fact that the Greeks were not acquainted with the city until it was taken and plundered by Alexander the Great.

It has been universally admitted that "the palaces" or "the palace" burned down by Alexander are those now in ruins at Takhti Jamshid. From Stolze's investigations it appears that at least one of these, the castle built by Xerxes, bears evident traces of having been destroyed by fire. The locality described by Diodorus after Cleitarchus corresponds in important particulars with Takhti Jamshid, for example, in being supported by the mountain on the east.

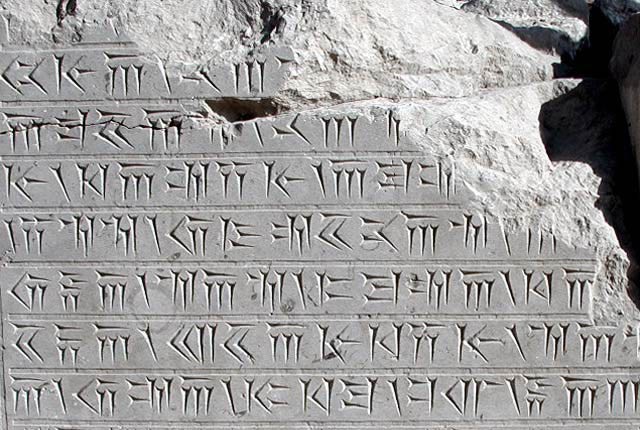

Ancient texts found in Persepolis

Photographer: Ramin Dehdashti of

iranpix.com

Scene from Persian mythology in Apadana Hall

Angra Mainyu kills the primeval

bull, whose seed is rescued by Mah, the moon,

as the source for all other

animals.

After invading Persia, Alexander of Macedonia sent the main force of his army to Persepolis, the Persian capital year the year 333 BC. By the Royal Road, Alexander stormed the Persian Gates (in the modern Zagros Mountains), then quickly captured Persepolis before its treasury could be looted. After several months Alexander allowed his troops to loot Persepolis. A fire broke out in the eastern palace of Xerxes and spread to the rest of the city. It is not clear if it had been a drunken accident, or a deliberate act of revenge for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens during the Second Greco-Persian War. Although many historians argue that while Alexander's army were celebrating with a symposium they decided to take revenge against persians in which case it would be a combination of the two. The Book of Arda Wiraz, a Zoroastrian work composed in the 3rd or 4th century CE, also describes archives containing "all the Avesta and Zand, written upon prepared cow-skins, and with gold ink" that were destroyed.

In 316 BC Persepolis was still the capital of Persia as a province of the great Macedonian Empire (see Diod. xix, 21 seq., 46 ; probably after Hieronymus of Cardia, who was living about 316). The city must have gradually declined in the course of time; but the ruins of the Achaemenidae remained as a witness to its ancient glory. It is probable that the principal town of the country, or at least of the district, was always in this neighborhood. About 200 CE we find the city Istakhr (properly Stakhr) as the seat of the local governors. There the foundations of the second great Persian Empire were laid, and Istakhr acquired special importance as the center of priestly wisdom and orthodoxy. The Sassanian kings have covered the face of the rocks in this neighborhood, and in part even the Achaemenian ruins, with their sculptures and inscriptions, and must themselves have built largely here, although never on the same scale of magnificence as their ancient predecessors. The Romans knew as little about Istakhr as the Greeks had done about Persepolis--and this in spite of the fact that for four hundred years the Sassanians maintained relations, friendly or hostile, with the empire.

At the time of the Arabian conquest Istakhr offered a desperate resistance, but the city was still a place of considerable importance in the first century of Islam, although its greatness was speedily eclipsed by the new metropolis Shiraz. In the 10th century Istakhr had become an utterly insignificant place, as may be seen from the descriptions of Istakhr, a native (c. 950), and of Mukaddasi (c. 985). During the following centuries Istakhr gradually declines, until, as a city, it ceased to exist. This fruitful region, however, was covered with villages till the frightful devastations of the 18th century; and even now it is, comparatively speaking, well cultivated. The "castle of Istakhr" played a conspicuous part several times during the Muslim period as a strong fortress. It was the middlemost and the highest of the three steep crags which rise from the valley of the Kur, at some distance to the west or north-west of Nakshi Rustam.

We learn from Asian writers that one of the Buyid (Buwaihid) sultans in the 10th century of the Flight constructed the great cisterns, which may yet be seen, and have been visited, amongst others, by James Morier and E. Flandin. W. Ouseley points out that this castle was still used in the 16th century, at least as a state prison. But when Pietro della Valle was there in 1621 it was already in ruins.

Wkipedia