Lessico

Farro

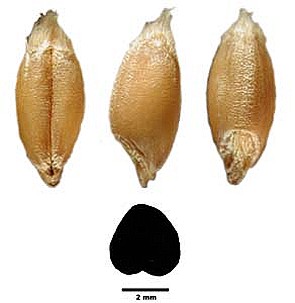

Triticum monococcum

dicoccum

spelta

Triticum

e Hordeum

acquarello![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi

di Ulisse Aldrovandi

Farro è il nome di alcuni cereali del genere Triticum

caratterizzati soprattutto dalle glumelle molto aderenti alle cariossidi, che

si staccano solo mediante una specie di brillatura, onde il nome di frumenti![]() vestiti con cui tali specie vengono distinte dalle congeneri. Se ne

conoscono tre tipi:

vestiti con cui tali specie vengono distinte dalle congeneri. Se ne

conoscono tre tipi:

Farro

piccolo o farragine (Triticum

monococcum![]() ) con

spighe fragili, erette a maturità, coltivato nel neolitico e oggi utilizzato

per il miglioramento genetico degli altri farri. Si ritiene essere originario

dell'Asia Minore, ivi coltivato già 5000 anni prima dell'era volgare.

Attualmente, oltre che nelle regioni d'origine, si coltiva solo in ristrette

zone d'Europa. –

Einkorn in inglese.

) con

spighe fragili, erette a maturità, coltivato nel neolitico e oggi utilizzato

per il miglioramento genetico degli altri farri. Si ritiene essere originario

dell'Asia Minore, ivi coltivato già 5000 anni prima dell'era volgare.

Attualmente, oltre che nelle regioni d'origine, si coltiva solo in ristrette

zone d'Europa. –

Einkorn in inglese.

Farro

medio o farro

propriamente detto (Triticum

dicoccum![]() ) con

spiga appiattita, pendente a maturità e due cariossidi per spighetta, il più

coltivato sin dall'antichità, il più importante cereale

dell'antico Egitto, la cui coltura è attualmente limitata a esigue regioni

montuose del vecchio continente – Emmer

in inglese.

) con

spiga appiattita, pendente a maturità e due cariossidi per spighetta, il più

coltivato sin dall'antichità, il più importante cereale

dell'antico Egitto, la cui coltura è attualmente limitata a esigue regioni

montuose del vecchio continente – Emmer

in inglese.

Farro

grande o spelta (Triticum

spelta![]() ) con

spiga cilindrica allungata, pendula a maturità, con due cariossidi per

spighetta. Originario dell'Europa centrale, ivi coltivato già nell'Età del Bronzo e

oggi solo in piccole zone della Germania sud-occidentale, della Svizzera e del

Belgio.– Spelt in inglese.

) con

spiga cilindrica allungata, pendula a maturità, con due cariossidi per

spighetta. Originario dell'Europa centrale, ivi coltivato già nell'Età del Bronzo e

oggi solo in piccole zone della Germania sud-occidentale, della Svizzera e del

Belgio.– Spelt in inglese.

Alica - Alica

è il termine latino che dovrebbe identificare il farro medio o farro

propriamente detto (Triticum dicoccum), emmer in inglese. L'etimologia

di alica è alquanto opinabile. Potrebbe derivare dal verbo alo,

nutrire - alica dicitur quod alit corpus (Festo Sesto Pompeo![]() )

- oppure dal greco álix (farina di farro o di riso), a sua volta

derivato da aléø, macinare. Nel testo di Gessner relativo al pollo

ricorre spesso alica, ma a confondere le idee interviene un vel

e un aut: alica vel far, alica aut farre. Io penso che si tratti di un

uso improprio di aut al posto di vel, per cui alica in

Gessner viene tradotto con farro (il farro propriamente detto o farro medio, Triticum

dicoccum), emmer in inglese, essendo il più coltivato sin dall'antichità

e usato anche dai Romani, per esempio durante il rito della comfarreatio

)

- oppure dal greco álix (farina di farro o di riso), a sua volta

derivato da aléø, macinare. Nel testo di Gessner relativo al pollo

ricorre spesso alica, ma a confondere le idee interviene un vel

e un aut: alica vel far, alica aut farre. Io penso che si tratti di un

uso improprio di aut al posto di vel, per cui alica in

Gessner viene tradotto con farro (il farro propriamente detto o farro medio, Triticum

dicoccum), emmer in inglese, essendo il più coltivato sin dall'antichità

e usato anche dai Romani, per esempio durante il rito della comfarreatio![]() , la

confarreazione, matrimonio religioso celebrato alla presenza del

pontefice massimo e di sei testimoni..

, la

confarreazione, matrimonio religioso celebrato alla presenza del

pontefice massimo e di sei testimoni..

Far - Meglio non disquisire sull'etimologia del latino far, il farro, da ricondurre, pare, all'indoeuropeo *bhares-, orzo. Comunque è stato far a dar luogo al vocabolo sia latino che italiano farina. Per quanto si è appena affermato circa la probabile identità tra alica e far, anche far viene tradotto con farro (il farro propriamente detto o farro medio, Triticum dicoccum), emmer in inglese.

Spelta - Spelta, usato per esempio da San Girolamo![]() , è un prestito germanico, e se il web dice il

vero, il tedesco Spelz indica l'involucro che avvolge il seme. Assente il

termine spelta nel testo di Gessner dedicato al pollo.

, è un prestito germanico, e se il web dice il

vero, il tedesco Spelz indica l'involucro che avvolge il seme. Assente il

termine spelta nel testo di Gessner dedicato al pollo.

Einkorn wheat (from German Einkorn, literally "one grain") can refer either to the wild species of wheat, Triticum boeoticum (the spelling baeoticum is also common), or to the domesticated form, Triticum monococcum. The wild and domesticated forms are either considered separate species, as here, or as subspecies of Triticum monococcum. Einkorn is a diploid species of hulled wheat, with tough glumes ('husks') that tightly enclose the grains. The cultivated form is similar to the wild, except that the ear stays intact when ripe and the seeds are larger.

Einkorn wheat was one of the earliest cultivated forms of wheat, alongside emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum). Grains of wild einkorn have been found in Epi-Paleolithic sites of the Fertile Crescent. It was first domesticated approximately 9000 BP (9000 BP +/- 8250 BCE), in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A or B periods. Evidence from DNA finger-printing suggests einkorn was domesticated near Karacadag in southeast Turkey, an area in which a number of PPNB farming villages have been found. Its cultivation decreased in the Bronze Age, and today it is a relict crop that is rarely planted. It remains as a local crop, often for bulgur (cracked wheat) or as animal feed, in mountainous areas of France, Morocco, the former Yugoslavia, Turkey and other countries. It often survives on poor soils where other species of wheat fail.

In contrast with more modern forms of wheat, there is evidence that the gliadin protein of einkorn may not be as toxic to sufferers of coeliac disease. It has yet to be recommended in any gluten-free diet.

Engrain

L’engrain ou petit épeautre

(Triticum monococcum) est une plante de la famille des Poacées (graminées),

première céréale domestiquée par l'homme, vers -7500, au Proche-Orient,

avec le blé amidonnier. L'engrain a une faible teneur en gluten, il n'est pas

panifiable. Le croisement "spontané" en situation de culture de l'engrain

et d'Aegylops tauschii a donné la famille des blés panifiables à

forte teneur en gluten.

L'engrain cultivé est une plante de petite taille, environ 70 cm. Les épillets

contiennent généralement un seul grain (d'où le nom allemand d'Einkorn).

C'est un blé « vêtu », à faible rendement, adapté aux sols pauvres et

arides. Son cycle de végétation est très long et se déroule presque sur

une année complète. La nécessité de le décortiquer réduit encore le

rendement net puisque le taux de balle dans le grain est proche de 30 %.

Cette espèce est originaire d'Asie mineure (Anatolie, Mésopotamie). Elle était déjà cultivée environ 7500 ans avant Jésus-Christ. Sa culture était répandue en Europe, mais elle a fortement régressé depuis le début du XX siècle. C'est désormais une culture relique. Il est encore cultivé en Espagne pour l'alimentation du bétail (fourrage). On le trouve aussi en Haute Provence où il a été redécouvert par le grand public il y a seulement une quinzaine d’années.

Il farro propriamente detto (Triticum dicoccum) è un cereale parente stretto del grano. Le prime menzioni di questo cereale si ritrovano nella Bibbia. Era conosciuto e coltivato nell'antico Egitto. Ezechiele lo usava come uno degli ingredienti per il suo pane (Ezechiele 4:9). La farina di farro costituiva la base della dieta delle popolazioni latine. Il pane di farro veniva consumato congiuntamente dagli sposi nel rito della comfarreatio, la confarreazione, matrimonio religioso romano celebrato alla presenza del pontefice massimo e di sei testimoni. Il suo nome deriva dai pani di farro (elemento specifico per riti consacratori) offerti dalla sposa, che venivano consumati ritualmente dalla coppia. Delle tre forme romane di matrimonio la confarreazione era l'unica che non prevedeva il divorzio e la sola valida per certi ruoli sacerdotali (per esempio i Flamini, voluti da Anco Marcio, il quarto dei sette re dell'antica Roma che regnò nella seconda metà del sec. VII aC), ruoli che dovevano essere espletati da uomini sposati.

Dopo la coltivazione di altre varietà di cereali, in particolare frumento, mais e riso, la coltura del farro è andata diminuendo nel tempo fin quasi a sparire. Oggi, riscoperto grazie alle sue ottime proprietà dietetiche, viene coltivato in Italia soprattutto in Toscana, nella Garfagnana, ai piedi delle Alpi Apuane, in provincia di Lucca. Il farro della Garfagnana ha ottenuto la certificazione di qualità IGP. Divenuto quasi una coltivazione "di nicchia", trova oggi una collocazione naturale nelle aziende biologiche.

Il farro cresce bene su terreni poveri di elementi nutritivi, in zone collinari tra i 300 e i 1.000 m s.l.m. La semina avviene in autunno, su terreno precedentemente preparato, utilizzando seme vestito. La preparazione del terreno non fa uso di diserbanti. La pianta è robusta e non abbisogna di concimi chimici o fitofarmaci, essendo resistente al freddo, alle malattie e agli agenti infestanti. La raccolta, più tardiva rispetto a quella del grano, si effettua in estate con le normali macchine usate anche per la mietitura del grano. Il seme si presenta in tre varietà: il farro piccolo, il farro medio e il farro grande o spelta (dal termine inglese spelt). Gli ultimi due sono quelli comunemente usati per la coltivazione.

La particolarità del farro è che il seme, a fine trebbiatura, conserva ancora l'involucro protettivo, per cui abbisogna di una ulteriore fase di lavorazione (denominata "sbramatura" o "brillatura"). Questo inconveniente, unito anche alla bassa resa, lo ha reso nel tempo meno "popolare" del grano ed ha di fatto spinto il coltivatore a rivolgersi verso colture più redditizie.La resa in brillato risulta pari a circa il 60-70% del prodotto iniziale.

Minestra di farro tipica della maremma toscana

Questo cereale si trova in commercio in due forme: il farro decorticato (o semplicemente farro) e il farro perlato. Il farrotto è un cereale "vestito", in quanto la glumetta, la pellicola esterna del chicco, ricca di fibre, è perfettamente aderente e quindi non viene eliminata dalla normale raffinazione con rulli cilindrici a cui è soggetto il frumento. Il farro decorticato conserva la glumetta intatta, che viene invece eliminata nel farro perlato, che si presenta di colore molto più chiaro e cuoce in un tempo decisamente inferiore.

La granella di farro brillata può essere ulteriormente macinata per la preparazione di paste, pane o biscotti. La farina di farro è utilizzata anche nell'industria dolciaria. Con la farina di farro si produce un ottimo pane, migliore di quello di frumento integrale poiché a parità di fibre non ha il tipico sapore di crusca, ma si avvicina molto al sapore del pane bianco, anzi è addirittura più aromatico e per certi aspetti migliore. In cucina è utilizzato soprattutto come ingrediente di zuppe e minestre ma si unisce molto bene coi legumi e le verdure esaltando gusti e profumi. Ottimo per insalate fredde, risotti ai funghi porcini. Si abbina in maniera eccellente ai vini rossi.

Emmer

Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum), also known as farro especially in Italy, is a low yielding, awned wheat. It was one of the first crops domesticated in the Near East. It was widely cultivated in the ancient world, but is now a relict crop in mountainous regions of Europe and Asia.

Strong similarities in morphology and genetics show that wild emmer (Triticum dicoccoides Koern.) is the wild ancestor of domesticated emmer (Triticum dicoccum). Because wild and domesticated emmer are interfertile with other tetraploid wheats, some taxonomists consider all tetraploid wheats to belong to one species, Triticum turgidum. Under this scheme, the two forms are recognized at subspecies level, thus Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccoides and Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum. Either naming system is equally valid; the latter lays more emphasis on genetic similarities.

Wild emmer (Triticum dicoccoides) grows wild in the fertile crescent of the Near East. It is a tetraploid wheat formed by the hybridisation of two diploid wild grasses, Triticum urartu (closely related to wild einkorn, Triticum boeoticum), and an as yet unidentified Aegilops species related to Aegilops searsii or Aegilops speltoides.

Like einkorn and spelt wheats, emmer is a hulled wheat. In other words, it has strong glumes (husks) that enclose the grains, and a semi-brittle rachis. On threshing, a hulled wheat spike breaks up into spikelets. These require milling or pounding to release the grains from the glumes.

Wild emmer grains are found at the archaeological site of Ohalo II in Israel, which have an uncorrected radiocarbon dating of 17,000 BC, and at the Pre Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) site of Netiv Hagdud (10,000-9400 years ago), also in Israel. Domesticated emmer however does not appear until around 7700 BC, the uncorrected radiocarbon date of the earliest find spot, Tell Aswad, 25 kilometers southeast of Damascus. Emmer wheat and barley were the dominant crops of the ancient Near East, and spread in the Neolithic to Europe and the Indian subcontinent.

In the Near East, in southern Mesopotamia in particular, cultivation of emmer wheat began to decline in the Early Bronze Age, from about 3000 BC, and barley became the standard cereal crop. This has been related to increased salinization of irrigated alluvial soils, of which barley is more tolerant. Emmer had a special place in ancient Egypt, where it was the only wheat cultivated in Pharaonic times, even though neighbouring countries also cultivated einkorn, durum and common wheat. In the absence of any obvious functional explanation, this may simply reflect a marked culinary or cultural preference. Emmer and barley were the primary ingredients in ancient Egyptian bread and beer. In Morocco DNA results of the cereals at Volubilis indicates significant occurrence of hulled emmer.

Emmer wheat is mentioned in ancient rabbinic literature (as one of the five grains forbidden to Jews during Passover). It is often incorrectly translated as spelt in English translations of the rabbinic literature but spelt did not grow in ancient Israel and emmer was a significant crop until the end of the Iron Age. Likewise, references to emmer in Greek and Latin texts are traditionally translated as "spelt," even though spelt was not common in the Classical world until very late in its history.

In northeastern Europe, Emmer (in addition to Einkorn and barley) was one of the most important cereal species and this importance can be seen to increase from 3400 BC onwards. Pliny the Elder, notes that although emmer was called far in his time formerly it was called adoreum (or "glory"), providing an etymology explaining that emmer had been held in glory (N.H. 18.3), and later in the same book he describes its role in sacrifices.

Wild wheat seeds (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) were discovered to self-cultivate by propelling themselves mechanically into soils with their awns. During a period of increased humidity during the nighttimes, the seed's awns become erect and draw together, and in the process push the grain into the soil. During the daytime the humidity drops and the awns slacken back again; however fine silica hairs on the awns act as hooks in the soil and prevent the seeds from reversing back out again. During the course of alternating stages of daytime and night time humidity, the awns' air powered pumping movements, which resemble a swimming frog kick, will drill the grain as much as an inch or more into the soil.

Today emmer is primarily a relict crop in mountainous areas. Its value lies in its ability to give good yields on poor soils, and its resistance to fungal diseases such as stem rust that are prevalent in wet areas. Emmer is grown in Morocco, Spain (Asturias), the Carpathian mountains on the border of the Czech and Slovak republics, Albania, Turkey, Switzerland and Italy.

Italy is an interesting case as, uniquely, emmer cultivation is well established and even expanding. In the mountainous Garfagnana area of Tuscany emmer (known as farro) is grown by farmers as an IGP (Indicazione Geografica Protetta) product, with its geographic identity protected by law. Production is certified by a co-operative body, the Consorzio Produttori Farro della Garfagnana. IGP-certified farro is widely available in health food shops across Europe, and even in some British supermarkets. The demand for Italian farro has led to competition from non-certified farro, grown in lowland areas and often consisting of a different wheat species, spelt (Triticum spelta).

Emmer's main use is as a human food, though it is also used for animal feed. Ethnographic evidence from Turkey and other emmer-growing areas suggests that emmer makes good bread (judged by the taste and texture standards of traditional bread), and this is supported by evidence of its widespread consumption as bread in ancient Egypt. Emmer bread is widely available in Switzerland. In Italy farro is traditionally consumed as whole grains, in soup. Its use for making pasta is a recent response to the health food market; some judge that emmer pasta has an unattractive texture.

Emmer wheat is closely related to durum wheat and common wheat and is therefore unsuitable for sufferers from wheat allergies or coeliac disease.

Amidonnier

L'Amidonnier (Triticum turgidum subsp. dicoccum) est une céréale à faible rendement appartenant au genre des blés (Triticum). C'est avec l'engrain la plus ancienne céréale domestiquée par l'homme, vers -7500, au Proche-Orient. Elle était très largement cultivée dans l'Antiquité, mais elle n'est plus, aujourd'hui, qu'une céréale résiduelle que l'on ne trouve que dans les régions montagneuses d'Europe et d'Asie. Il provient de l'amidonnier sauvage (Triticum dicoccoides). Celui-ci est également à l'origine du blé dur (Triticum durum), que l'homme a obtenu par sélection. Il existe deux variétés d'amidonnier cultivé : l'amidonnier blanc, également appelé épeautre de mars ou épeautre de Tartarie, et l'amidonnier noir.

De grandes similarités génétiques et morphologiques montrent que l'amidonnier sauvage est l'ancêtre de l'amidonnier domestiqué. Parce que les amidonniers sauvages et domestiqués sont interfertiles avec les autres blés tétraploïdes (en particulier avec le blé dur), certains taxinomistes considèrent que tous les blés tétraploïdes appartiennent à une seule espèce, le Turticum turgidum. Selon cette classification, l'amidonnier sauvage et l'amidonnier domestiqués sont considérés comme des sous espèces, et désignés respectivement comme Triticum turgidum L. subsp. dicoccoides et Triticum turgidum L. subsp. dicoccum. Chacune de ces dénominations est équivalentes, le second système se fondant sur les similarités génétiques . Dans cette seconde classification, le blé dur est alors nommé Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum.

L'épi présente un axe fragile, aplati sur le sens du profil, aux barbes courtes et faibles pour l'amidonnier blanc, plus longues pour l'amidonnier noir. Le grain est vêtu, de couleur rougeâtre. les balles restent adhérentes au grain à la maturité, ce qui rend plus difficile la mouture. Le grain produit, cependant, une farine blanche et très riche en amidon -d'où le nom français de la céréale.

La Spelta, antenata del frumento e varietà del farro (Triticum spelta) è un cereale molto antico, originato probabilmente 8.000 anni or sono, nell'Asia sud-occidentale nell'area chiamata storicamente Mezzaluna fertile dall’incrocio tra la specie Triticum dicoccum e la Aegilops squarrosa.

La specie Spelta è quella che più si avvicina al grano tenero anche da un punto di vista cromosomico, ossia esaploide: la spiga è lunga e sottile e le sue spighette, circa una ventina, si chiamano rachidi. Ogni rachide contiene a sua volta da due a tre chicchi ricoperti di glume. I chicchi vengono separati dalla glume tramite un apposito procedimento di brillatura. Lo stelo è di colore rossastro e lungo circa 1 metro e 1/2. La spelta contiene un’elevata quantità di fibre e di glutine.

È una pianta che si sviluppa facilmente su terreni ben esposti al sole anche se poveri, ma è stata soppiantata nel corso del tempo da altre colture più redditizie. Proprio come la segale, veniva coltivata anche per le sue caratteristiche zootecniche, allo scopo di ricavarne paglia, oppure utilizzata per la copertura di capanne; la sua produzione è ancora attiva soprattutto in Francia, Germania e Svizzera. Con la farina di spelta (dal sapore forte e di colore scuro) si producono tipici biscotti piatti come il "panpepato" e, di recente, si è ricominciata una limitata produzione di pane.

Spelt

Spelt (Triticum spelta) is a hexaploid species of wheat. Spelt was an important staple in parts of Europe from the Bronze Age to medieval times; it now survives as a relict crop in Central Europe and has found a new market as a health food. Spelt is sometimes considered a subspecies of the closely related species common wheat (Triticum aestivum), in which case its botanical name is considered to be Triticum aestivum subsp. spelta.

Spelt has a complex history. It is a hexaploid wheat species known from genetic evidence to have originated as a hybrid of a domesticated tetraploid wheat such as emmer wheat and the wild goat-grass Aegilops tauschii. This hybridization must have taken place in the Near East because this is where Aegilops tauschii grows, and it must have taken place prior to the appearance of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum, a hexaploid free-threshing derivative of spelt) in the archaeological record c. 8000 years ago.

Genetic evidence shows that spelt wheat can also arise as the result of hybridization of bread wheat and emmer wheat, although only at some date following the initial Aegilops-tetraploid wheat hybridisation. The much later appearance of spelt in Europe might thus be the result of a later, second, hybridization event between emmer and bread wheat. Recent DNA evidence supports an independent origin for European spelt, through this hybridization. However whether spelt has two separate origins in Asia and Europe, or single origin in the Near East, is currently unresolved.

The earliest archaeological evidence of spelt is from the fifth millennium BC in Transcaucasia, north of the Black Sea. However, the most abundant and best-documented archaeological evidence of spelt is in Europe. Remains of spelt have been found in some later Neolithic sites (2500 - 1700 BC) in Central Europe. During the Bronze Age, spelt spread widely in central Europe. In the Iron Age (750-15 BC), spelt became a principal wheat species in southern Germany and Switzerland, and by 500 BC also in southern Britain.

References to the cultivation of spelt wheat in Biblical times (see matzo), in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, and in ancient Greece, are incorrect, and result from confusion with emmer wheat.

In the Middle Ages, spelt was cultivated in parts of Switzerland, Tyrol and Germany. Spelt was introduced to the United States in the 1890s. In the 20th century, spelt was replaced in almost all those areas in which it was still grown by bread wheat. As spelt requires fewer fertilizers, the organic farming movement made it more popular again towards the end of the century.

Spelt contains about 57.9 percent carbohydrates (excluding 9.2 percent fibre), 17.0 percent protein and 3.0 percent fat, as well as dietary minerals and vitamins. As it contains a moderate amount of gluten, it is suitable for baking. In Germany, the unripe spelt grains are dried and eaten as Grünkern, which literally means "green grain".

Spelt is closely related to common wheat, and is not suitable for people with celiac disease. It is possible that spelt is suitable for people with a wheat allergy or intolerance, and if this is the case spelt can be a good substitute for common wheat.

The

name of spelt in Hungarian is "tönköly", in German is Dinkel, and

the hull which covers the seed is called Spelz. Hulled grains, which don't

thresh freely like modern wheat, were identified by this quality and the term

"spelt wheats" was often used in nineteenth century English to mean

hulled wheats in general, not just spelt wheat.

The Luxembourger surname Speltz is derived from this grain. In Italy both

emmer wheat and spelt are known as farro, although emmer is more common in

Italy. In France spelt is known as épeautre. In Romania it is known as alac.

The Spanish terms for spelt are espelta or escaña mayor. Historically, in Spain spelt has only been grown in Asturias, where it is known as escanda.

Spelt flour is becoming more easily available, being sold in UK supermarkets since 2007. Spelt is also sold in the form of a coarse pale bread, similar in colour and in texture to light rye breads but with a slightly sweet and nutty flavour. Cookies and crackers are also produced, but are more likely to be found in a specialty bakery or health food store than in a regular grocery store. Spelt pasta is also available in health food stores and speciality shops.

The raw grain when chewed releases trace amounts of gluten giving the mass a slight resilience, not unlike gum (whereas wheat becomes a sticky glutinous mass, similar to thick jam). The texture is slightly crunchy. The nutty flavour is more intense than it is in most breads and some prefer the raw substance to the baked goods.

Dutch jenever makers distill a special kind of gin made with spelt as a curiosity gin marketed for connoisseurs. Beer brewed from spelt is sometimes seen in Bavaria.

Épeautre

L'épeautre, appelé aussi « blé des Gaulois » est une céréale, plante de la famille des poacées, proche du blé mais vêtue (le grain reste couvert de sa balle lors de la récolte). L'épeautre est considéré par certains auteurs comme une sous-espèce du blé tendre (Triticum aestivum) sous le nom de Triticum aestivum L. subsp. spelta (L.) Thell. L’épeautre est aussi appelé « grand épeautre » par opposition au « petit épeautre » ou engrain, autre espèce de céréale rustique du genre Triticum.

Le rendement de cette céréale est très faible et elle a été délaissée au profit de variétés de blés à plus haut rendement. Une de ses autres caractéristiques est son enveloppe (glumelle) qui est très dure mais c'est aussi une qualité: les moisissures n'atteignent pas le grain. Cette peau est très riche en silicium. Grâce à ses racines profondes, elle peut pousser sur des terrains très pauvres, peu fertilisés et très secs. Ce qui en a fait une céréale plus facilement utilisable dans l'agriculture biologique. Elle est utilisée en boulangerie, notamment pour la fabrication de pains. Elle sert aussi pour faire des pâtes alimentaires.

Les premières mentions de cette céréale se retrouvent dans la Bible (cousmine ou couseimaite en hebreu moderne). Elle était connue et cultivée dans l'Égypte antique. Ézéchiel l'employait comme ingrédient pour faire son pain (Ézéchiel 4:9). La farine d'épeautre constituait la base du régime alimentaire des populations latines. Après la culture d'autres « variétés » de céréales, en particulier froment, maïs et riz, la culture de l'épeautre a régressé progressivement jusqu'à disparaître presque totalement. Devenu presque une culture de « niche », il trouve aujourd'hui sa place naturelle dans les exploitations biologiques.

L'épeautre pousse bien dans des sols pauvres en éléments nutritifs, dans des régions de collines entre 300 et 1000 mètres d'altitude. Le semis intervient en automne, sur un sol préparé précédemment, et se fait à l'aide de grains vêtus. La préparation du sol ne nécessite pas l'usage de désherbant. La plante est robuste, résistante au froid, aux maladies et aux autres infestations, et peut se passer d'engrais chimiques ou de produits phytosanitaires. La moisson, plus tardive que pour le blé tendre, se fait en été avec les moissonneuses-batteuses habituelles.

La particularité de l'épeautre est que le grain conserve après le battage les enveloppes ou glumelles qui restent adhérentes (comme c'est le cas pour d'autres céréales, orge, riz...). Cela impose ensuite une opération de décorticage. Cet inconvénient, qui s'ajoute aussi au faible rendement de cette culture, explique qu'elle est devenue moins « populaire » que le blé et a de fait poussé les agriculteurs à se tourner vers des cultures plus rentables. Le rendement après décorticage est d'environ 60 à 70 % du produit initial.

En cuisine, l'épeautre est utilisé surtout comme ingrédient de soupes et potages, mais il se marie bien avec les légumes exaltant saveurs et parfums. Excellent pour les salades froides, le riz aux cèpes. S'accorde très bien avec les vins rouges. Les grains d'épeautre décortiqués peuvent ensuite être moulus pour la fabrication de pâtes, pains et biscuits. La fabrication du pain à base de farine d'épeautre nécessite un peu moins d'eau car la pâte a tendance à "lâcher" et coller. L'épeautre est intéressant pour ses valeurs nutritionnelles exceptionnelles. Cette céréale est plus riche en protéines, mais aussi en magnésium, en zinc, en fer et en cuivre que son "grand frère" le blé. Ses protéines sont plus riches que celles d'autres céréales en lysine, un acide aminé essentiel. La farine d'épeautre est également utilisée dans la fabrication industrielle de confiserie.