Lessico

acquarello![]() di Ulisse Aldrovandi

di Ulisse Aldrovandi

D’Arcy

Thmpson in A glossary of Greeks birds (1895) cita numerosi autori

antichi che hanno parlato o accennato ai combattimenti delle quaglie: Luciano![]() (in Anacharsis

(in Anacharsis![]() ),

Platone

),

Platone![]() (in Lysis), Plutarco

(in Lysis), Plutarco![]() (i combattimenti tra le quaglie di Antonio e Augusto

(i combattimenti tra le quaglie di Antonio e Augusto![]() ),

Ovidio

),

Ovidio![]() .

Riferisce inoltre che questo sport è ancora comune - nel 1895 - sia tra i

Cinesi che tra i Malesi, e che

era praticato in Italia ai tempi di Aldrovandi, soprattutto a Napoli. Infatti

Aldrovandi vi dedica un paragrafo apposito nel II volume della sua Ornithologia,

riportato più avanti

.

Riferisce inoltre che questo sport è ancora comune - nel 1895 - sia tra i

Cinesi che tra i Malesi, e che

era praticato in Italia ai tempi di Aldrovandi, soprattutto a Napoli. Infatti

Aldrovandi vi dedica un paragrafo apposito nel II volume della sua Ornithologia,

riportato più avanti![]() .

.

acquarello di Ulisse Aldrovandi

Comportamento della quaglia

Coturnix quail are for the most part gentle and calm birds that tolerate the presence of others well. During the summer months the males become walking hormones and have a fighting good time. The fighting is normally not lethal but they can blind each other if they are too crowded. Quail are very territorial when they have a brood. The males will chase other quail and other broods off to ensure food for their own chicks. The females rarely get into these territorial disputes, it's a job for the male. It is sheer bedlam when we feed quail during brooding time. The males are all squared off fighting each other (no one ever gets hurt) while the females quietly herd their chicks around the fisticuffs and continue feeding along with them. If a quail family is foraging and runs into another quail family, the males will fight for the foraging area. These fights are more ceremonial than real. The two males stretch upright and bump each other around with their chests. They threaten with their beaks, but the blow never lands. The strongest male will prevail and gets the area for his family. If a quail family is foraging and runs into a childless pair, a single gesture by the father is all that is required. The childless couple will quietly give up the area to the family and as quietly move away.

Aristotele

Historia animalium IV,9: Alcuni lanciano grida mentre combattono, come la quaglia, altri a mo’ di sfida prima del combattimento, come la pernice, altri ancora dopo la vittoria, come i galli. In certi gruppi di uccelli, i maschi cantano al pari delle femmine: per esempio cantano sia l’usignolo maschio sia la femmina [In realtà canta solo il maschio, ma è facile confonderlo con la femmina (AW, ad loc.)], ma quest’ultima cessa di cantare quando cova e ha i suoi piccoli. In altri gruppi sono soprattutto i maschi a cantare, come ad esempio i galli e le quaglie, mentre le femmine non cantano. (traduzione di Mario Vegetti)

Plinio

Naturalis historia XI,268 Avium loquaciores quae minores, et circa coitus maxime: aliis in pugna vox, ut coturnicibus, aliis ante pugnam, ut perdicibus, aliis cum vicere, ut gallinaceis. isdem sua maribus, aliis eadem et feminis, ut lusciniarum generi. quaedam toto anno canunt, quaedam certis temporibus, ut in singulis dictum est.

Platone

Dialogo L’Alcibiade maggiore: Midia, che era un personaggio malfamato e un demagogo, faceva l'allevatore di quaglie; Aristofane, Gli uccelli, 1297, lo denomina quaglia. L'ironia di Socrate* è molto forte, dato che anche Alcibiade era un appassionato allevatore di quaglie, come molti giovani ateniesi, che se ne servivano per combattimenti e giochi simili a quelli dei galli.

Amores, II,6,27-28: Ecce, coturnices inter sua proelia vivunt;/forsitan et fiunt inde frequenter anus. - Ecco, le quaglie vivono in mezzo ai loro combattimenti;/forse anche per questo spesso diventano vecchie.

Vite parallele, Antonio 33,1-3: After this settlement, Antony sent Ventidius on ahead into Asia to oppose the further progress of the Parthians, while he himself, as a favour to Caesar, was appointed to the priesthood of the elder Caesar; everything else also of the most important political nature they transacted together and in a friendly spirit. But their competitive diversions gave Antony annoyance, because he always came off with less than Caesar. [2] Now, there was with him a seer from Egypt, one of those who cast nativities. This man, either as a favour to Cleopatra, or dealing truly with Antony, used frank language with him, saying that his fortune, though most great and splendid, was obscured by that of Caesar; and he advised Antony to put as much distance as possible between himself and that young man. "For thy guardian genius," said he, "is afraid of his; and though it has a spirited and lofty mien when it is by itself, when his comes near, thine is cowed and humbled by it." [3] And indeed events seemed to testify in favour of the Egyptian. For we are told that whenever, by way of diversion, lots were cast or dice thrown to decide matters in which they were engaged, Antony came off worsted. They would often match cocks, and often fighting quails, and Caesar's would always be victorious. At all this Antony was annoyed, though he did not show it, and giving rather more heed now to the Egyptian, he departed from Italy, after putting his private affairs in the hands of Caesar; and he took Octavia with him as far as Greece (she had borne him a daughter). (published in the Loeb Classical Library, 1920)

Ulisse Aldrovandi

Ornithologiae tomus alter Liber XIII - Cap. XXII De Coturnice Latinorum - Pugna - pag. 161-162: [161] Perdices pugnaces esse diximus, et id fortassis Coturnicibus potius competere dicendum est, nam Aristoteles, vel saltem quisquis ille fuit Physiognomicorum author, aves, ait quibus durae sunt pennae, fortes esse, et pugnaces, quas inter Coturnices, et Gallinaceos nominat. Pugnant autem, vel legitimo Aristotele [HA L.9 cap.8] teste, pro faeminis [feminis], et inter caelibes etiam mas victus victoris venerem patitur mansuetaeque, inter se spectaculi gratia certaturae committuntur ut referemus: Plinius [X,21] Pergami certamen Gallinaceorum quotannis publice edi solere prodidit. Id et Athenis factitari caeptum, author est Aelianus [Lib.2 Var. C.28 in Anacha<r>side], a T<h>emistocle superatis Persis. Lucianus adiicit et Coturnicum certamina, eaque ibidem spectari non suevisse tanti decoris, ut ad illa tanquam ad gladiatorum munus effusissimo studio omnes convenirent. Quinimo [Quin immo] Solonem narrantem inducit legem Atheniensibus fuisse, ut iuvenes Coturnicibus et Gallis pugnantibus spectandis tempus impenderent, ut eiuscemodi avium rostris ad extremam usque virium defectionem pugnantium certamina, intuentes ad fortiter subeunda pericula, et contemnenda vulnera, ne [???] avibus ingenerosiores haberentur, inflammarentur. Ita Herodianus Severi filios scribit, dissidere solitos puerili primum certamine edendis Coturnicum pugnis, Gallinaceorumque conflictibus. Eiuscemodi enim aves in tali ludrico certamine productae, vel etiam sua sponte invicem dimicant, mutuisque ictibus collidunt, caput et cervicem erigentes. In nonnullis Italiae urbibus maxime Neapoli pugnaces etiamnum alunt, et ex earum certaminibus maximam voluptatem, et etiam lucrum saepe percipiunt: certaturis primo milium ad satietatem offerunt, dein super oblongam aliquam mensam ab utraque scilicet parte unam collocant: illae more Gallinaceorum invicem torve aspicientes, quasi minarentur, quid audaciter praestituras, tacitae subsidunt, et [at?] mox non aliter ac si duo fortissimi equites in vallo concurrerent, ubi ad aliud milium, quod in media mensa ponitur pervenere, tanto ardore, tantaque velocitate invicem aggrediuntur, manusque conserunt, ut nisi evulsis sibi pennis, ac sanguine ex acceptis vulneribus {esiluente} <exiliente> a pugna discedant, atque tam diu dubio marte dimicant, donec alterutra, tanquam se victam facta, victori locum cedat, ac pudibunda aufugiat. Tunc vero victoris dominus pramio [praemio], de quo certatum est, potitur, victricemque suam magni aestimat, adeo ut si ita aliquoties acie vincat, decem, et duodecim saepe aureis vendat. Quanti vero apud priscos fieret eiuscemodi certamen, cum ex paulo ante dictis, tum vero exemplo potissimum Augusti Caesaris innotut???, qui Erotem Aegypti praefectum quod victricem per contumeliam edisset, mortuaeque??? animi??? multavit. Et longe ante tempora Caesaris divinus Plato [In Lyside] eos redarguens, qui nimis illis tribuerent, [162] quanto in pretio haberentur, innuit, Potius, inquiens, ego mihi amicum probum optaverim, quam optimam (strenuissimam scilicet) inter homines Coturnicem, aut Gallinaceum. Sed an semper ita invicem dissideant, ut Ovid.[In epitaphio psittaci] mihi in sequenti disticho innuere videtur, dum scribit inde facile senescere, me latet, quamvis id facile credam.

Ecce

Coturnices inter sua praelia vivunt,

Forsitan, et fiunt inde

frequenter anus.

Sed nonnulli viri docti pro praelia prandia legunt, ut scilicet ad elleborum, quo Coturnices pasci scripsimus, referatur, at qui elleboro vesci dixerunt, non ex huiusmodi esu senescere voluerunt, ut hic Ovidius, at contra pinguescere; quare non male meo iudicio praelia legendum, quemadmodum etiam, quotquot ego vidi exemplaria habent. Porro Aristides sophista apud Philostratum hanc pugnacitatem innuens cuidam deprecanti, ne Sparta muris cingeretur, respondisse fertur: ne capita illi damus moenibus Coturnicum assumpto ingenio. Huc pariter spectat quod Aristophanes [In pace] Carcini poetae filios òrtygas ou kogheneis, idest, domesticas Coturnices, aut potius domi genitas vocaverit, quod videlicet domi continue inter se contenderent: quare ortyghìou psychlon échein, hos est Coturnicula animam habere, parum recte, utpote contra avis naturam, proverbialiter de formidoloso, et pusillanimo homine Antiphanes comicus apud Athenaeum hoc versu p<r>otulit.

Sý tí

poiêin dýnasai ortyghíou psychlin échøn.

Tu quid facere vales, Coturnicula animum habens.

Meticulosi enim homines non pugnant, vel si cogantur pugnare, terga, ubi possunt, vertunt: e contrario Coturnix sponte dimicat, et nisi victa, ac plerunque [plerumque] nisi vulneribus acceptis pugnam deserit. Haud ab re fuerit hic docere, quomodo Coturnices per se alias pugnaces, pugnaciores reddantur. Dioscorides [Lib.4 cap. 131] author est Adianti herbae esu ad pugnam accendi. Quod si itaque pugnantium domini milii vice pugnaturis exhibuerint praeliabuntur audacius, adversariasque facile superabunt. Id vero inter Coturnicum, Perdicum, et Gallorum praelium differentiae est, quod illae in pugna cantent, Perdix ante aggressam dimicationem, Gallus post debellatum hostem. (I punti interrogativi denotano una stampa illeggibile)

Anacarsi Scita

In greco Anácharsis, considerato uno dei sette sapienti, gli si attribuiscono molti scritti e l'invenzione dell'ancora e della ruota da vasaio. A Scythian philosopher, who lived about 600 B.C. He was the son of Gnurus, chief of a nomadic tribe of the Euxine shores, and a Greek woman. Instructed in the Greek language by his mother, he prevailed upon the king to entrust him with an embassy to Athens about 589 B.C. He became acquainted with Solon, from whom he rapidly acquired a knowledge of the wisdom and learning of Greece, and by whose influence he was introduced to the principal persons in Athens. He was the first stranger who received the privileges of citizenship. He was reckoned one of the Seven Sages, and it is said that he was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. After he had resided several years at Athens, he travelled through different countries in quest of knowledge, and returned home filled with the desire of instructing his countrymen in the laws and the religion of the Greeks. According to Herodotus he was killed by his brother Saulius while he was performing sacrifice to the goddess Cybele. It was he who compared laws to spiders' webs, which catch small flies and allow bigger ones to escape. His simple and forcible mode of expressing himself gave birth to the proverbial expression " Scythian eloquence," but his epigrams are as unauthentic as the letters which are often attributed to him. According to Strabo he was the first to invent an anchor with two flukes.

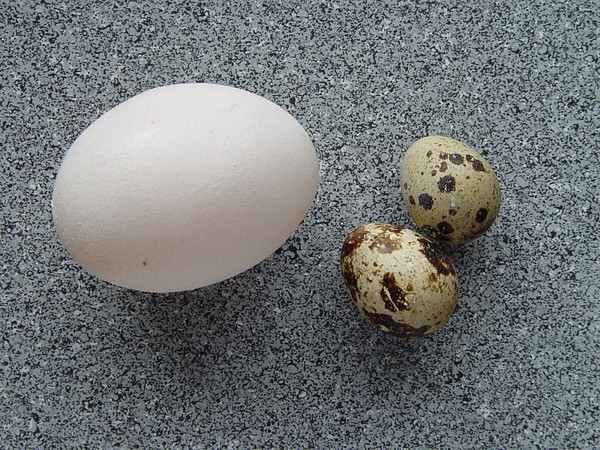

Uova di quaglia paragonate a un uovo di gallina